Thanks to RuPaul Charles and his reality project Drag Race, people across the planet are consuming the art form of drag in copious amounts. It seems to have gained a slightly elevated status and a significant portion of heteronormative society are celebrating what was once taboo, something LGBTQ+ outcasts of previous generations could have only dreamt about. “America’s next drag superstar”, a coveted title and the highest accolade in the drag entertainment industry, puts competing queens on track for a fruitful career and mainstream acceptance. The Drag Race empire, over a decade in the making, now attracts the attention of millions across the globe and with successful infant-stage international spin-offs there is no sign of this counterculture phenomenon fading any time soon. Although drag may be new to many, it has been a queer staple for decades with a centuries long history.

Women were forbidden from taking part in Shakespearean production due to the patriarchal rules of the day, as the performance stage was closely tied to the church men would take on the role of the opposite gender during shows. Even the etymology of the word drag has deep roots in religious theatre, purporting to the trailing dresses that men wore on set. Young male actors playing the few female characters in the late 16th century onwards hardly represent the queer struggle associated with gender non-conformity in more recent times, however this one-dimensional type of drag continued for centuries.

Eminent straight female impersonators such as Julian Eltinge enjoyed tremendous success in the vaudeville scene of the late 1800s onwards. Variety entertainment such as vaudeville had a strong focus on comedy and evolved from the likes of freak show exhibitions and racist minstrelsy. Clowns, acrobats and trained animals were advertised alongside incognito men and even intersex people. While these entertainment forms subsided just after the turn of the 19th century, a clear rhetoric on gender bending was emerging; this dehumanisation of trans and gender variant people still exists today.

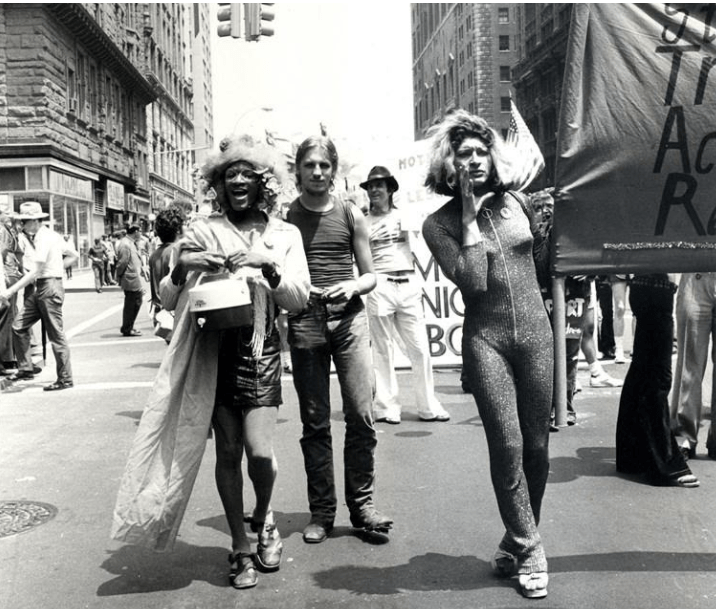

After the liberal 1920s the US was hell-bent on the cracking down of homosexual behaviours, banning cross-dressing and enforcing the nuclear family ideal. During the subsequent reactionary decades, expressing queerness was dangerous and pushed underground. That said, a very small number of white men broke through the scepticism associated with drag to achieve more widespread success, including Danny La Rue, an Irish gay singer and entertainer whose drag persona first appeared in Britain in the 1950s. Transatlantic gay bars during the middle decades of the 20th century offered a respite from heteronormativity for queer people on both sides of the pond. Society at large continued to criminalize homosexuality, albeit the Genovese family and other New York mafia clan provided the bricks and mortar for queer party goers and underhandedly LGBTQ+ activism. Stonewall in the Manhattan Greenwich Village was raided by the police for a final time in 1969, when prominent gender diverse folk and queens of colour, including Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, fought back initiating six days of riots, protests and demonstrations: the largest gay liberation movement in history.

As the decriminalisation of homosexuality was under way, one demographic was left behind. The LGBTQ+ community of colour, trans folk especially, had long been at the forefront of gay liberation movements, yet they were side-lined while the world started to accept the white middle-to-upper class queers. Safe spaces for gay and gender non-conforming folk of racial minority groups cropped up in the guise of competitive balls in the 1970s. Queens walked runway categories fighting face, body and attitude; triumphant ones pranced away with highly desired trophies. House counterculture was birthed, seasoned contenders known as mothers or fathers took in younger protégés, often exiled from their family homes, and provided them with mentorship, shelter and sisterhood. Pose, which features the largest cast of trans actors in the history of TV and film, showcases ballroom culture in all of its beauty, glory and struggle.

From an economic perspective, drag was unprofitable, queens booked small gigs in niche gay districts of inner cities. However, as the 80s rolled into the 90s, the club kid aesthetic gained traction in the nightlife industry, catapulting some queens and gender variant people into celebrity status, notably transgender Amanda Lepore and… RuPaul Charles. Ballroom and vogueing entered the popular culture realm following the release of the Paris is Burning documentary and Madonnas hit Vogue, both in 1990. NYC drag was exploding, RuPaul headed a MAC cosmetic campaign in 1994, the first queen to do so, at the same time Linda Simpson alongside eight fellow club scene queens featured on the cover of the New York Magazine. Mainstream celebration of drag in the mid-90s was short-lived, 24 years lapsed before the New York publication covered another queen.

Ultimately it was up to RuPaul to bring drag back into the lives of many. The success of the Drag Race franchise provided a lifeline to a community that have hustled without pay-off for far too long. Queens in the US are now bagging high fashion campaigns, Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty Fashion Show extravaganza was not only a cultural reset, but it afforded us the luxury of witnessing Jaida Essence Hall, Shea Couleè and Gigi Goode stomping around in lingerie. Today, drag is far from one-dimensional, subcultures exist within the larger counterculture movement itself, from the surge in TikTok and Instagram queens to the re-emerging club kid scene, the boundaries of what is drag are limitless. In the latest US season of Drag Race, Gotmikk is further breaking the mould of conventional drag. Despite Ru’s previous reluctance to inclusion, they are the first female-to-male transgender contestant to grace our screens, proving that anyone on the queer spectrum can produce good drag.

Drag and gender diverse people have a shared history, albeit with their own distinct tribulations. Many notable drag queens and kings along with LGBTQ+ activists have experimented with both their gender identity, the way they express that and the performance art we have grown to love. Now that RuPaul has acknowledged drag transcends gender, its future is even more exciting.

Featured Image: William Yang / National Library of Australia