Where are you right now? A house? A flat? A care home? A prison? Homeless?

They say coronavirus doesn’t discriminate, but the distribution of property is the product of a rigid, highly discriminatory class system. The distribution of education is a postcode lottery, and, funnily enough, one that the wealthy tend to win.

And the distribution of resources is in the hands of the government. This government has cut almost 200,000 council houses in the last ten years. Every stop on the Jubilee Line from Westminster to Canning Town represents one year shorter lifespan for its residents. So, stripped of public life, the UK can be seen all the more clearly for what it is: a patchwork of stark contrasts. Space suddenly seems the most valuable possession we can own.

As the coronavirus lurks at the forefront of the public consciousness, the loudest voices are often the ones sat on Twitter in their back gardens with a glass of bubbly, ranting about people they’ve just seen sunbathing in the park. Breaking the lockdown! Risking lives! Disgraceful! We aren’t all living through lockdown in the same way. For lots of people, daily exercise is the only opportunity to leave the house, whilst people with paddocks for back gardens can roam all day.

There’s something gloating about a sunburnt face in the current times. Because, whilst no one has the freedom to move where we want, the restrictions are far more invasive on those confined to one room on the seventh floor of a block of flats than those who have a private segment of the outside world at their fingertips. The virus doesn’t discriminate, but we do. It is time we realise that coronavirus isn’t impacting everyone in the same way.

Our lowest-paid workers aren’t able to hibernate and wait for the virus to pass. They are out delivering new clothes to people ensconced in luxury homes. They are the NHS workers whose idea of luxury is adequate PPE, and the shop assistants, who risk their lives to suffice your Haribo cravings. The safety of lockdown is far from universal.

For instance, ethnic minority citizens are dying at a disproportionately high rate. Despite constituting just fourteen per cent of the population, they account for approximately one-third of the deaths. One expert said that social deprivation was the strongest reason for mortality because of an increased underlying burden of disease. Minorities are overrepresented in cramped accommodations and in frontline jobs. This virus is the fire, lighting a tinder of structural inequality, swollen by austerity, NHS cuts and housing shortages. Now we see the devastating effects.

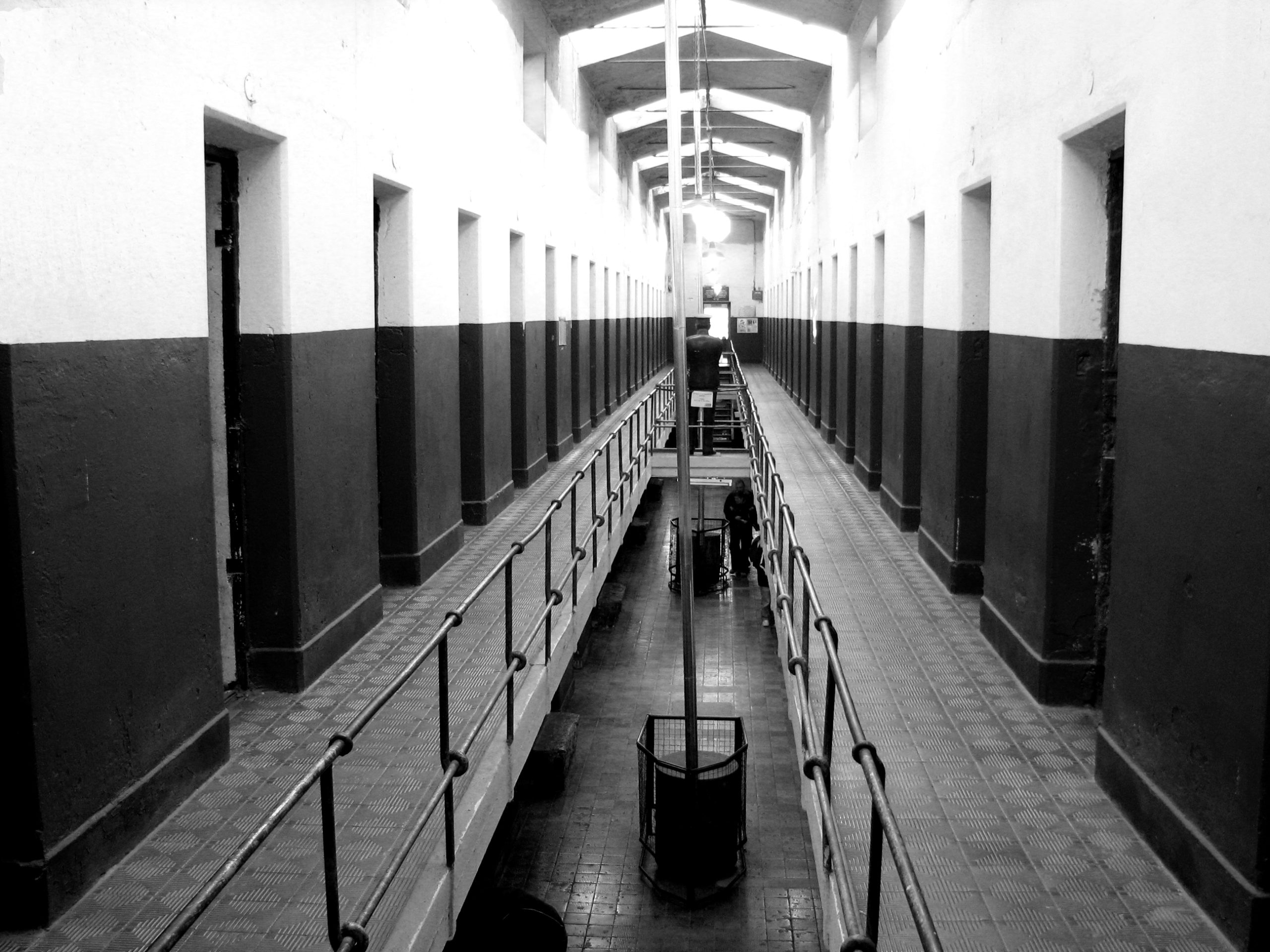

And yet, there is another section of society which is at great risk. Prisons have been left to sustain themselves on a diet of overcriminalization and underfunding in recent years. This makes it difficult to keep prisoners apart. A prisoner described his ordeal as an infected inmate, saying the staff “don’t want to talk to you, they just want you to shut up, be in there and get well or die.”

In Columbia, twenty-one people died in a protest over unsanitary prison condition due to coronavirus fears. One prisoner said he felt they’d been “abandoned like dogs” in the midst of the outbreak. Prisons are a haven for transmission, and now, not only deprive people of liberty but safety too.

The coronavirus is not a ‘grand leveller’ of inequalities. It does not pose the same risk to everyone, and it certainly won’t be going away without taking an even greater toll on life. When it sweeps through refugee camps and overpopulated, poverty-stricken cities, there will be hugely detrimental repercussions. For now, we must wait it out, and hopefully, when we emerge, we will not be so blind to the divisions across the country and the world.

Amy Ramswell

Image: Wikimedia Commons.