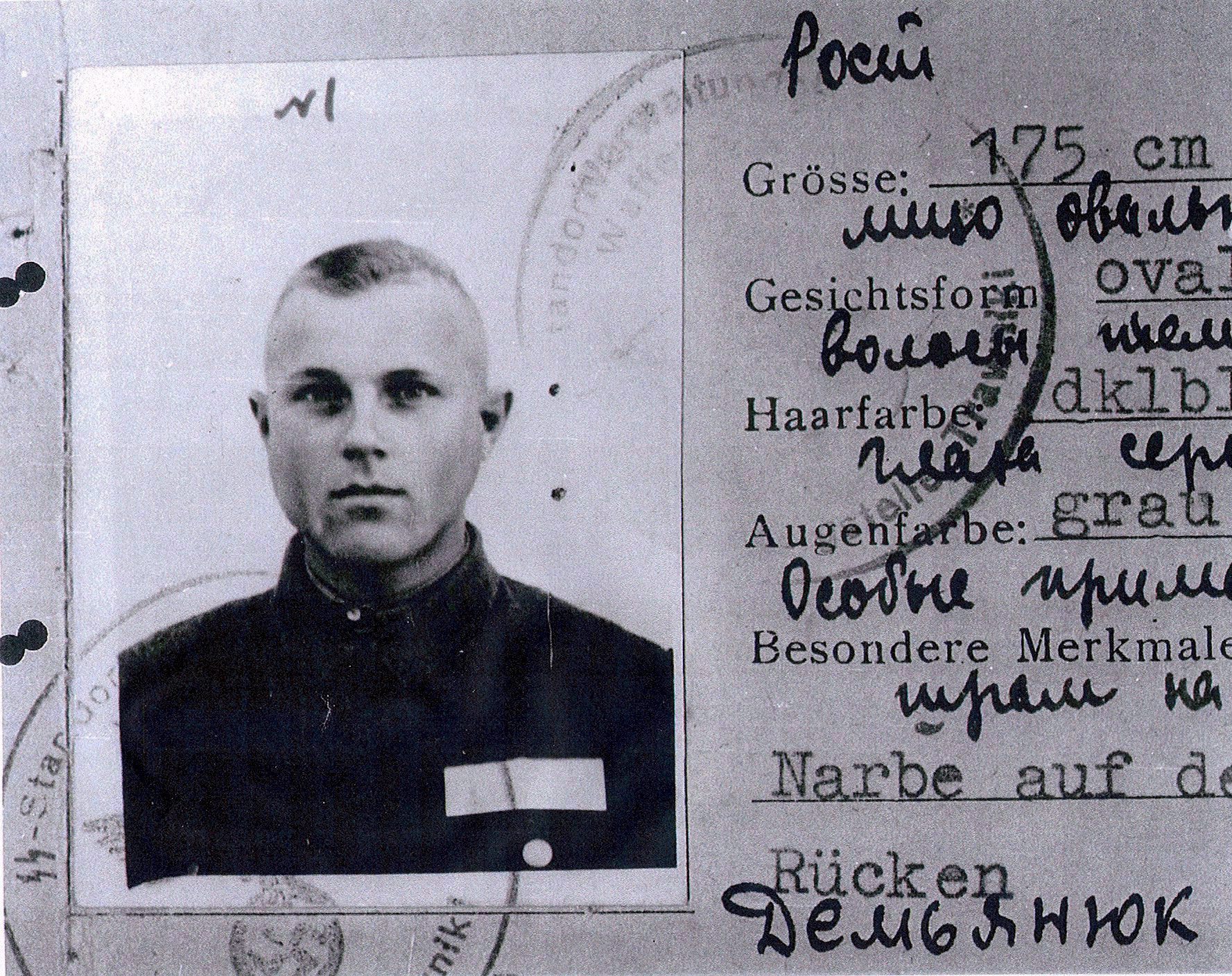

After the Second World War, John Demjanjuk emigrated to the US in search of the American Dream. He was able to live there as a ‘normal Cleveland guy’. In 1986, he was accused of being the infamous ‘Ivan the Terrible’, an executioner who operated the gas chambers at Treblinka, a death camp in Poland during World War Two. Demjanjuk denied these charges, claiming it was mistaken identity. Despite this, Treblinka survivors were willing to testify against him and he was extradited to Israel to face the death penalty.

In March 2020, HistSoc organised for Eli Gabay, a member of the Israeli prosecution team for Demjanjuk’s case, to visit the University of Leeds to discuss the extradition and prosecution of Holocaust war criminals. After watching the Netflix documentary series, The Devil Next Door, about Demjanjuk’s case, it is clear that Demjanjuk was guilty of being a Nazi guard during the Holocaust. Despite this, it is less clear as to whether he was ‘Ivan the Terrible’.

The documentary brings into question whether these war criminals should still be being prosecuted at all. In 2009, as the OSI in the US continued to pursue Demjanjuk for his actions in the concentration camps, some felt that it was no longer worth anything. He depicted himself as an ill, elderly man, causing some members of the public to doubt his ability to carry out these terrible acts he was being accused of.

Many Nazi War Criminals went to live in the USA after WWII with the US government’s knowledge, but no action was taken because they were seen as an asset against the spread of Communism. However, both The Devil Next Door and Gabay’s talk demonstrated that the actions of these criminals left victims of concentration camps scarred for the rest of their lives. Therefore, why should these war criminals, who inflicted pain and suffering on innocent individuals, be allowed to retreat into the American Dream without consequence?

Even if he wasn’t Ivan the Terrible, he was still guilty of being part of the Holocaust. He may have been an old man at that point, but to simply do nothing and let Demjanjuk live the rest of his life with no retribution would be criminal. As Gabay argued, anyone helping to run the concentration camps was a participant in murder, rendering them guilty. Time doesn’t absolve people of guilt.

Another question arose from Gabay’s talk, concerning the survivors. In Demjanjuk’s original trial, these survivors were brought to the stand and once they had given their testimonies, they were questioned. It seems inhumane to question whether they’re sure of what they went through. This intense questioning was clearly an attempt to certify that they hadn’t misremembered, were senile, or that they were lying. This unrelenting questioning was tortuous, but it was the only way to identify Demjanjuk as ‘Ivan the Terrible’. It was clear that if survivors got up on the stand, pointed at Demjanjuk and said that the man sitting in front of them was ‘Ivan the Terrible’, which is what Rosenburg, one of the survivors, did, then there was no way that anyone could argue against them. To this end, the prosecution team had to advise the survivors from a legal point of view. Lawyers are not historians: they were there to collect the most damning pieces of evidence necessary in order to convict, or not convict, accused war criminals.

This case revealed more than just one man’s guilt. It also demonstrated that though time has passed, these crimes continue to affect survivors. Their lives could not be lived in the same way afterwards, so why should the war criminals who inflicted emotional and physical damage on them be allowed to continue as though nothing happened? Many have now died, but the argument remains. Any crime against innocent people, no matter how long ago, still happened. The victims deserve more than for people to ignore crimes which will never disappear.

Demjanjuk died in March 2012 at the age of ninety-one, before the verdict for his appeal had been heard. His guilt was revoked. Under German law, he remains innocent.

Ana Hill Lopez-Menchero

Image: Wikimedia Commons.