Following months of campaigning and media coverage, you might be forgiven for thinking that we must be a fair way through the US Presidential Election process by now. In actual fact, things are only just getting started.

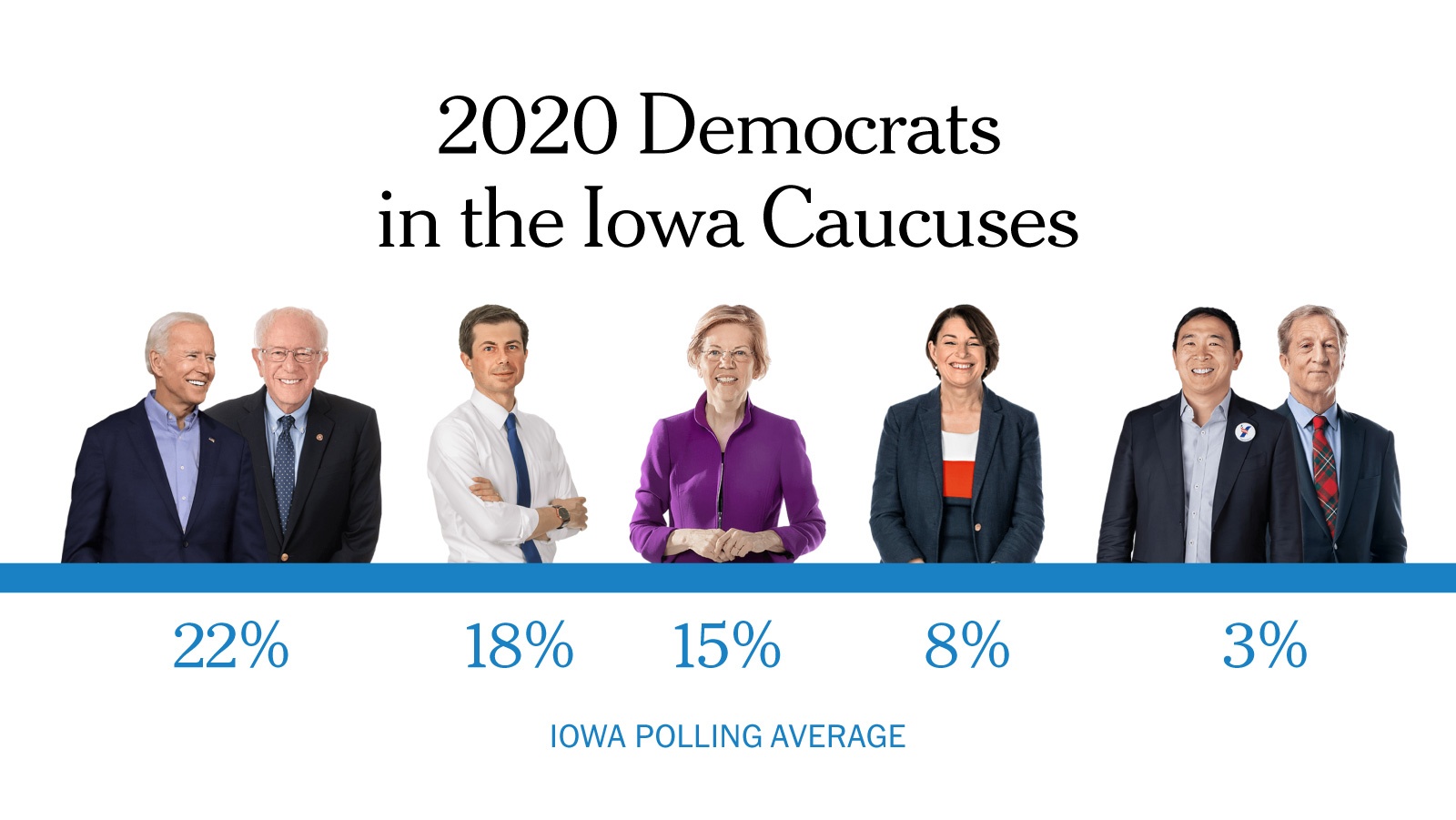

Tuesday the 4th of February marked one of the biggest days in the Democratic election calendar – the Iowa Caucus. The party is currently in the process of choosing the candidate that will run for Presidency in the latter half of this year. Starting with 28, 12 candidates now remain in the running, though only 4 of these are really considered to be in with a reasonable chance of victory.

Despite its relatively small size, Iowa is considered to be a pivotal location in electoral terms. Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden have near enough established residency there over the last month in order to focus their campaign efforts on the small Midwestern state.

Iowa has a long history of being a significant indicator of electoral success – with the last four winners of the Iowa Caucus having gone on to secure the Democratic nomination for presidency. Iowa has been the first stop on the nomination trail since 1972 and not once in 48 years has anyone who finished fourth or worse in either party gone on to achieve success in the overall nomination contest.

Analysts propose that the Iowa phenomenon arises because winning the first caucus vote gives candidates valuable momentum that propels them forward in the lengthy contest, which ends with the official nomination announcement in Wisconsin in July. It also gives candidates a chance to review in the early stages of campaigning what elements of their strategies are resonating with voters and what it is that they need to change.

On Tuesday, a fault with the introduction of a new mobile app designed to improve the caucus voting process resulted in mass chaos and confusion, as the results were significantly delayed and multiple candidates began claiming victory before any official numbers were actually released. Following the considerable delays, the former mayor of Indiana – and potential dark horse of the race – Pete Buttigieg came out on top in the preliminary results, with Bernie Sanders following in at a close second.

Donald Trump was quick to capitalise on the chaos, declaring the night an ‘unmitigated disaster’ for the party and declaring that the ‘Do Nothing Democrats’ could hardly be fit to run the country if they could not even successfully administer one small caucus vote. However, beyond the frivolous jibing on Twitter, the incident also brought to attention a much bigger question over the continued significance of the Iowa caucus in today’s political environment.

As a cross-section of the electorate, Iowa is far from representative of the general US voting population. Delivering 41 out of 1991 delegates, Iowa’s population is 86% white and largely rural. It is difficult to find a convincing justification for an electoral process that places so much importance on a state as small and unrepresentative as this. Candidates spend a huge amount of time and effort campaigning in Iowa; potentially raising the worry that they might amend their campaign priorities to suit Iowa voters, at the expense of other demographic groups who do not reside in the Midwest.

It has also been suggested that the Iowa obsession may discriminate against minority candidates who cannot garner the votes they need in the almost all-white state. Kamala Harris and Cory Brooker – two ethnic minority hopefuls for the Democrat nomination – both recently dropped out of the leadership race after failing to rally the support they needed to progress in the nomination process. If the first caucus had been held in New York, California or somewhere even slightly more reflective of the hugely diverse US population, perhaps the same thing may not have happened.

Iowa is one part of a much bigger question about the suitability of the highly complex US electoral system – which favours candidates with big budgets, affords advantages to incumbents who can redraw district lines in their favour and frequently results in the candidate with the most votes losing the fight for presidency. Famous for being set in its ways, the US seems a long way off from reforming its electoral process. Moreover, its enduring relevance in today’s modern, multicultural society is highly questionable.

Image: The New York Times