For the last week international attention has turned to China after a new virus, the Coronavirus or nCov, emerged from the city of Wuhan in the country’s Hubei province. Speculation as to the origins of the Coronavirus have been widely debated, but as of Tuesday over 4500 cases have been officially reported across 5 continents with a death toll over 100. This number is steadily rising. Despite these official reports, given China’s history with the 2003 SARS virus (a cousin to the current strain) and its slow response to nCov’s outbreak in December, we in the international community cannot trust China to be transparent as it fights this epidemic.

The virus has spread to Europe, and the British government are currently attempting to track down around 2000 people who have travelled through Wuhan in the last two weeks who could potentially have brought the virus back with them. The government are also looking into plans to safely evacuate the 300 Britons who are currently thought to be trapped in the quarantined city of Wuhan.

Even though official reports of the virus put its spread at just over 4500, with a suspected 7000 cases including the ones currently being tested for, many people believe that the real numbers may be much higher and that China may be covering up the full extent of the outbreak as they did with SARS in 2003. Looking at the timeline of events it’s easy to understand why.

Between the 1st December and the 2nd January, China reported 41 cases of the nCov virus but played down the need for international concern. For the next 16 days no new cases would be reported, though the government continued to promote and host an event in which forty thousand families got together for an annual banquet, giving the virus ample opportunity to spread. In this time it is also claimed that it started putting pressure on the World Health Organisation not to designate nCov a public health risk.

As the number of official cases continues to climb, critics of the Chinese government have accused it of taking a number of actions to suppress news about the virus including lying about the infection rate, censoring the media, and even attempting to remove critical videos from the internet. One such video shows a Chinese nurse claiming that as many as 90,000 people have been infected. Given these factors and their track record, the international community has to operate under the assumption that the Chinese government are being neither transparent nor co-operative and assume the worst in preparing to tackle this problem.

But what does that mean for us in the UK, tucked away about five and a half thousand miles from the source of the outbreak?

Due to China’s track record and behaviour, we probably won’t have a reliable source on infection numbers in Wuhan for a while yet, and as such cannot be certain of nCov’s inability to develop into a pandemic. Nor should we rule out the possibility of it mutating and becoming more severe. Despite this, one thing we definitely shouldn’t do is panic.

At some point in the future the UK will face a major viral threat. Whether it is the nCov virus or something further down the line history paints it as a near inevitability. What we need to be doing in the short term is preparing to face this as a serious threat until we understand the virus better. In the long term we also need to ensure the international community as a whole responds a lot more effectively to these crises as they develop in the future. This means harsher sanctions on countries if they suppress information on new diseases, quicker responses to diseases as they emerge, and better global resources set aside to tackle epidemics as the occur.

Right now, the scariest factor is that there’s still so much we don’t know. What we do know is that thousands of times more people die from flu annually each year than nCov has killed so far. There’s no need to be buying gas masks and stocking up on tinned food just yet. The Coronavirus represents a type of threat that we, as a global society, can tackle.

Matthew Jeffrey

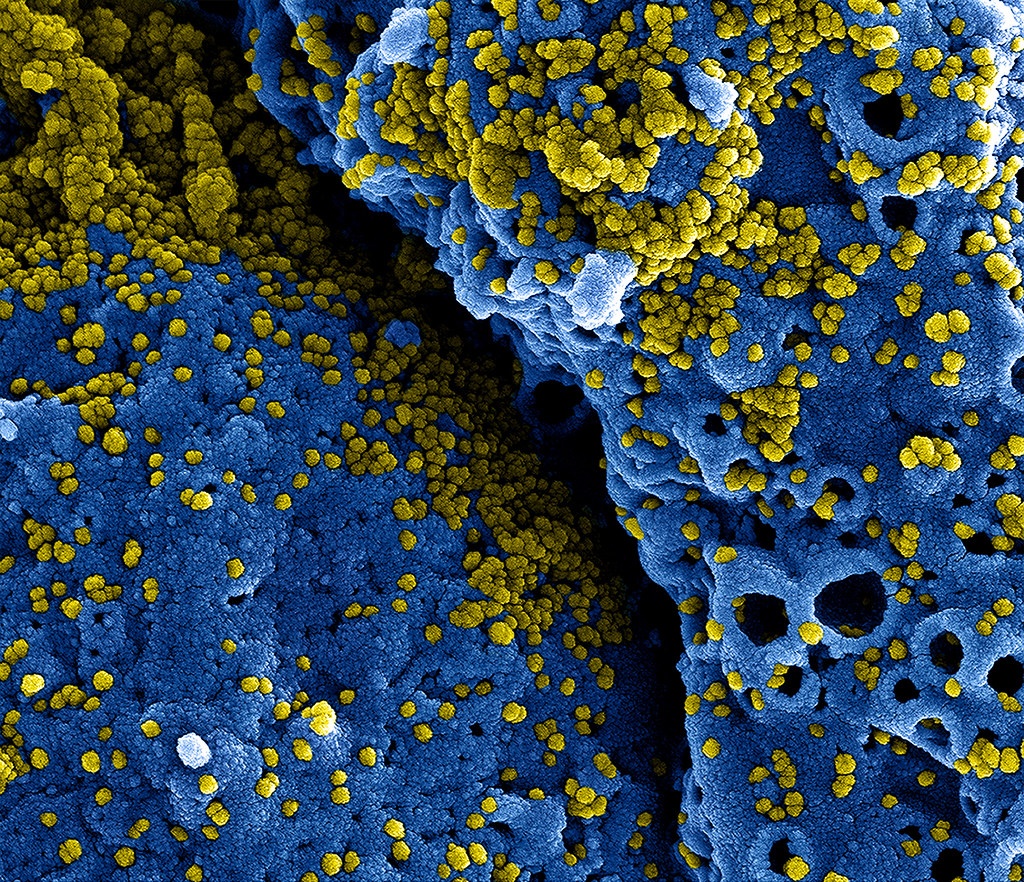

Image: Flickr.