When bringing one of Oscar Wilde’s most recognisable and beloved works to the stage, translating his charm and energy from paper to the physical world is vital to any production’s success. Although the play opened on shaky footing, Eve Walton’s modernisation of the original text kept the play fresh and funny, and then scary and poignant.

For the most part, the play’s plot stayed faithful to original book, with some slight variations and a small twist at the end. After selling his soul and acquiring a beautiful painting of himself, Dorian Gray falls into a life of hedonism, privilege, and moral corruption. This culminates in the death and/or ruin of nearly all the play’s cast, including Dorian himself.

Where the play shined though was when it brought this formula to the modern world. The barrage of voicemails left to Dorian’s phone in increasing urgency really stood out as one of these moments. This modern formatting did a great job of conveying the devastation left in Dorian’s wake in such as way as to make a more modern audience really start to appreciate the desperation of some of the play’s powerless characters.

Unfortunately, the charm and tension that seemed to flow through most of the play weren’t present in the opening minutes, and it was only after characters started spending a bit of time with each other that they seemed to warm up to each other and the play really hit its stride. For example, Basil’s love for Dorian seems almost forced when he’s talking about him in the play’s opening moments. And yet, Toby Oldham’s characterisation of Basil seemed subtle, sincere and genuinely moving as soon as he was given the chance to move about the stage and interact with other characters more.

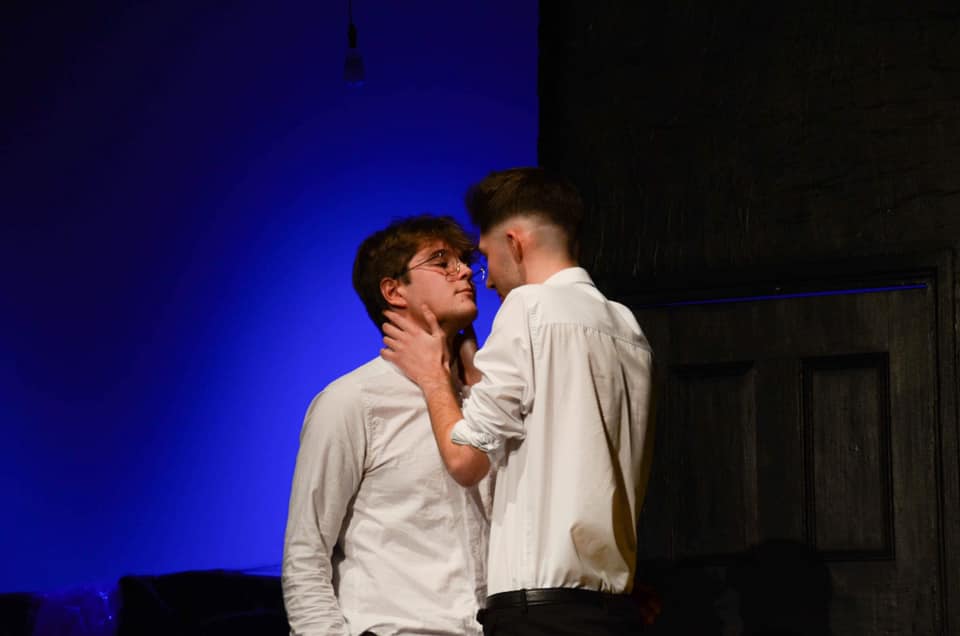

Although the play started with a lack of energy it soon picked up and by the play’s climax, Tom Gibson’s transformation of Dorian from wide-eyed and innocent to a dashing yet grotesque villain was not only believable but also gripping and disturbing. Most of the other characters were not afforded arcs as pronounced as the play’s lead unfortunately, but despite this the smaller arcs many of them had gave actors plenty of opportunities to shine. In particular, Dec Kelly’s fall into poverty as Adrian Parker and Ellen Hardy facing blackmail and shame as Grace Hobson struck particular chords with their respective portrayals of issues that remain very prevalent to this day. And it’s this capacity to remain relevant to modern issues that really gave the play its shining moments.

One character this adaptation explored more was Harry Wotton, played to the full potential of his sneering charisma, upper-class privilege, and general awfulness. Throughout the play, he is able to do what he wants when he wants and he never feels the repercussions of his actions. He is manipulative, regressive, and vicious up until the play’s end and, with much credit to George Marlin, savagely funny even when the play starts to take a darker tone. It is Harry that saves himself at the expense of everyone else at the play’s closing, and Harry himself who almost dictates when the play should end with the shutting of a book. It’s in these moments that Oscar Wilde’s warning of upper-class privilege and corruption seems most poignant in today’s climate.

An Interview with Dorian Grey’s director: Eve Walton

Wanting to find out a bit more about the adaptation process, I managed to speak to Eve Walton who not only adapted the text to the stage but also directed the play.

What made you want to adapt Dorian Gray?

Well, I had this idea of how to do it with all of the homoerotic subtext brought out. So I jumped straight in and enjoyed it and it just sat there for a couple of years because I was never quite happy with it and I could never figure out why. And then I re-read the book this May. I went “I’m not reading the full version I’m reading the censored version”. When it was published at least four chapters were removed for being too explicit, too graphic, too hedonistic.

So I read the full version and I thought “This is perfect, I want to work with this”. And there wasn’t an adaptation of the full version, only of the censored version. So I went back to it as soon as I’d read that. Oh, and I wanted to scare people.

What do you think were the biggest challenges you faced adapting the text?

I think I found it quite difficult early on in reading and in writing the first draft. I had someone read over it and they said “Halfway through, it starts to sound like you’re writing it”. When I first started writing it I had the chapter open in front of me and I just pulled out dialogue wherever it was and tried to modernise it. It was more of a translation than an adaptation. It was because I was trying to be so faithful to what Wilde had done, especially when it came to dialogue that I was missing my own style a little bit. So I then had to stop looking at the text word for word and start reading the text first and then re-writing the scene myself. There were some quotes, for example “Everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power” which had to be in the show. But there were other times I wanted to write something that was more modern. So there were lines like “There are only five women in London worth having conversations with and two of them used to be men” because it did seem to me, for example, that Harry would definitely be transphobic. So there were times where I did get to put more of myself into the play which at first I was scared to do.

Do you have any other adaptations in store for the future?

I don’t have any particular things I want to adapt at the moment. But I think editing and adapting are two things I really want to get into. Looking at other scripts and the idea of translation and transformation. I think I enjoy adapting more than writing to be honest, I made a joke about how Wilde is a great writing partner. Even though I’m obviously not writing with him it feels like I am because I’m working with his text. So I would like to do some more in the future.

Whatever the cast and crew of Theatre Group’s Dorian Gray have for us next, we’ll certainly have high expectations.

Image Credit: Abby Swain