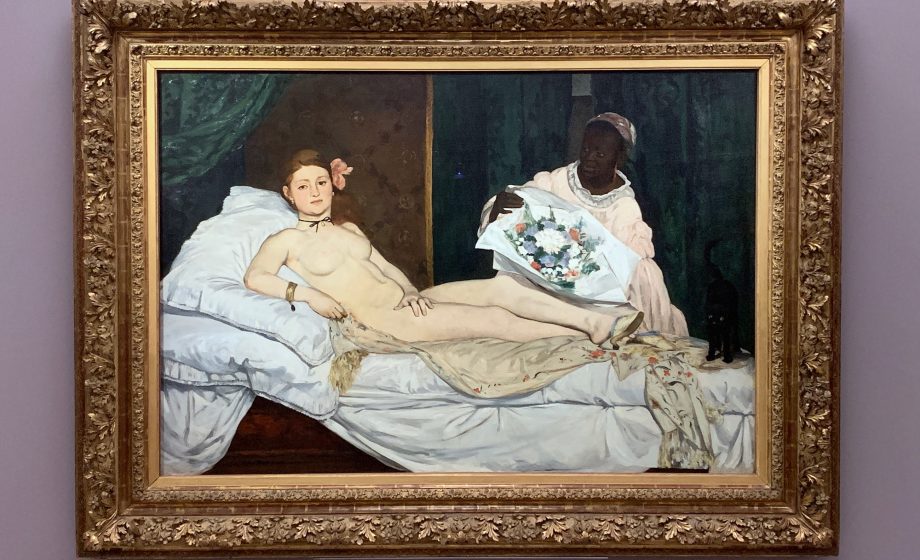

A new exhibition taking place at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris is challenging conceptions of fine art, due to the mainstream art scene often excluding people of colour. The exhibition is called “Le modèle noir: de Géricault à Matisse”, meaning “Black Models: from Géricault to Matisse” and will feature a number of French masterpieces, renamed after their black subjects. For example, Edouard Manet’s famous ‘Olympia’, which depicts a white naked prostitute and a woman of colour posing as her maid, has been renamed Laure, after the black model.

People of colour feature throughout modern art, and yet have been systematically ignored and uncredited. Where they have been referenced in titles it has often not been by name but solely through racial labels such as ‘negresse’. Lilian Thuram, president of the French foundation for education against racism, explained that at the time an image of a white woman would never be called ‘portrait of a white woman’, but ‘portrait of a woman’, whereas models of colour were exclusively defined by their ethnicity. By renaming the artwork in this exhibition, the museum seeks to present the models as individuals. In doing this the exhibition also shines a light on the deep rooted issues in art history. For example, the identity of the woman who modelled for Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s ‘Portrait of a Negress’, now renamed ‘Portrait of Madeline’, was never sought until now, over 200 years after it was painted. American scholar and co-curator of the exhibition, Denise Murrell, explained that “this is emblematic. It was art history that left them out. It has contributed to the construction of these figures as racial types as a opposed to the individuals they were”.

Further to this, ignoring the role people of colour have played in the development of Western art plays to the unspoken narrative that the field predates multiculturalism. Whilst contemporary art is more open to diversity, there is an image of empire which the world of fine art needs to shake. This is not only as a result of prejudices from the periods in which major artists were working, but due to contemporary curation which plays to this narrative. By renaming these paintings after the black models in them, this exhibition showcases to visitors that Western fine art couldn’t have developed without people of colour. It is an important example of how the context in which we view art can play a major role in how we perceive it.

Thus, context plays a major role in the exhibition; visitors can appreciate the art, appreciate the subjects of the art, and yet acknowledge the history of the piece. The people of colour depicted in the artworks are almost exclusively painted in subservient roles. Does the exhibition of these pieces therefore aid to perpetuate the colonial narratives of the period in which they were painted? I would argue no. These images chronicle the history of oppression both within the world of art and more broadly. We cannot erase the oppression, and by drawing focus onto those being oppressed, the exhibition forces audiences to think more carefully about the stories behind the artworks.

The question arises of whether is it enough to simply ‘rename’ past artworks; would it not be of more value to exhibit works by artists of colour, so that they may actively present their own experience? That is not to say that the Musée d’Orsay is not taking some steps in the right direction; the exhibition does include reinterpretations of paintings by contemporary artists, such as Congolese artist Aimé Mpane’s Olympia II. Mpane reimagines Manet’s Olympia but with a woman of color being served by a white maid. Furthermore, the Musée d’Orsay is not alone in taking strides; The Museum of Modern Art in New York has announced an extension, dedicating 40,000 sq ft of new space for women, Latino, Asian, African-American and other overlooked artists. Its board says this is an acknowledgment that there is no single or complete history of modern and contemporary art and that many of MoMA’s holdings have historically been overlooked. Hopefully, the progress in these institutions may signal a change in the exclusive bubble of the world of art.

Image Credit: Musee D’Orsay