With last Thursday marking ‘National Coming Out Day’, Tom Poole reflects on ‘queerness’ within the music industry, and how artistic output has served to challenge conventions in recent years.

I had just turned 13 when I heard Macklemore’s ‘Same Love’ for the first time. I wasn’t yet into music all that much, but following the success of ‘Thrift Shop’, Macklemore in 2012 was as inescapable as ‘Gangnam Style’ had been the same year. I adored the tune, and the contrast in style between its relaxed piano chords and the more upbeat likes of ‘Can’t Hold Us’ intrigued me. It was only after having it on repeat for weeks that I really heard the lyrics.

At the time, I knew my older brother had a friend who he had described as ‘gay’, and as a 13-year-old, ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ are hurled across the playground as wrongful and ill-understood insults all the time. I don’t think I had a strong grasp on what being gay really meant, though. I certainly had no idea about what being queer was.

Essentially, ‘Same Love’ opened my eyes to the LGBTQ+ community – a community which, at the time, I had only had fleeting interactions with, or at least nothing to make me think too deeply on the subject. ‘Same Love’ was my first proper interaction with any sort of discourse on being queer – and it was coming from a straight bloke.

If this is the impact one song from one artist – an artist I didn’t really relate to all that much, and who identifies as heterosexual and binary – can have on somebody, just imagine the impact any LGBTQ+ artist may have on young listeners who identify as queer or are confused about their identity.

The reality for a lot of young people in the UK is that a serious lack of queer representation in most media means, for many, their first impressions of LGBTQ+ life is from snippets of pop culture. Often, queer representations are limited; reduced to stereotypes, plot devices, or comic relief. There are some more positive representations, but often LGBTQ+ characters fail to be fleshed out fully, and rarely transcend their sexuality with any sort of alternate personality traits other than that they are simply queer.

Queer people seeing themselves represented well in their interests is essential, just as for anyone seeing themselves represented is. Even reading Frank Ocean’s open letter or seeing Brendan Urie perform at the American Music Awards is enough; enough to tell them that queer people can be successful in the media; enough to tell them that queer people can move past the social barriers often put in their way.

Take Sam Smith, a modern gay icon, and the first openly gay artist to perform a James Bond soundtrack – a franchise criticised for being tediously hypermasculine and heteronormative. Smith planted the flag somewhere it had never been before. He’s achieved multi-platinum albums, and even won an Oscar.

Alternatively, think of Janelle Monáe, whose music focuses on sexual empowerment. Monáe tells her listeners not only that they are above those who insult them, but that they shouldn’t care, both with tongue-in-cheek lyricism and by exuding massive confidence in her own sexuality. Smith inspires queer audiences with popular music; Monáe inspires with empowering music.

Modern queer artists empower queer sexuality in a way that those of old could not. LGBTQ+ musicians strive to become respected in their own right, rather than simply using queer iconography to promote any sort of brand. Queer listeners can hear this music and really connect with it; they can feel like they share an experience with someone, belonging to an identity that goes ignored all too often.

Think Bowie, the great icon of androgyny, famed for the sexuality of his Ziggy Stardust alter-ego. His look was popular because of how strange it seemed – not praised for pushing the boundaries of gender and sexuality that it did. The 1972 The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars album, especially tracks like ‘Starman’, allude to the idea that Bowie was alien.

Even if Boy George and new wave may have temporarily popularised gender exploration in men and women, this music wasn’t for queer people – it instead utilised queer identity as a stage trait, made it a symbol of ‘alternative’, further confusing mainstream ideas of ‘queer’ and otherwise.

But it’s Monáe and Smith, and the new army of queer creators, who are leading the way for great, positive LGBTQ+ icons. They aren’t ‘queer musicians’; they are musicians who are also queer. Integrating their own identities into their music is an incredible experience for those that may follow it, and it brings something fresh to otherwise stale genres by celebrating identities previously gone ignored.

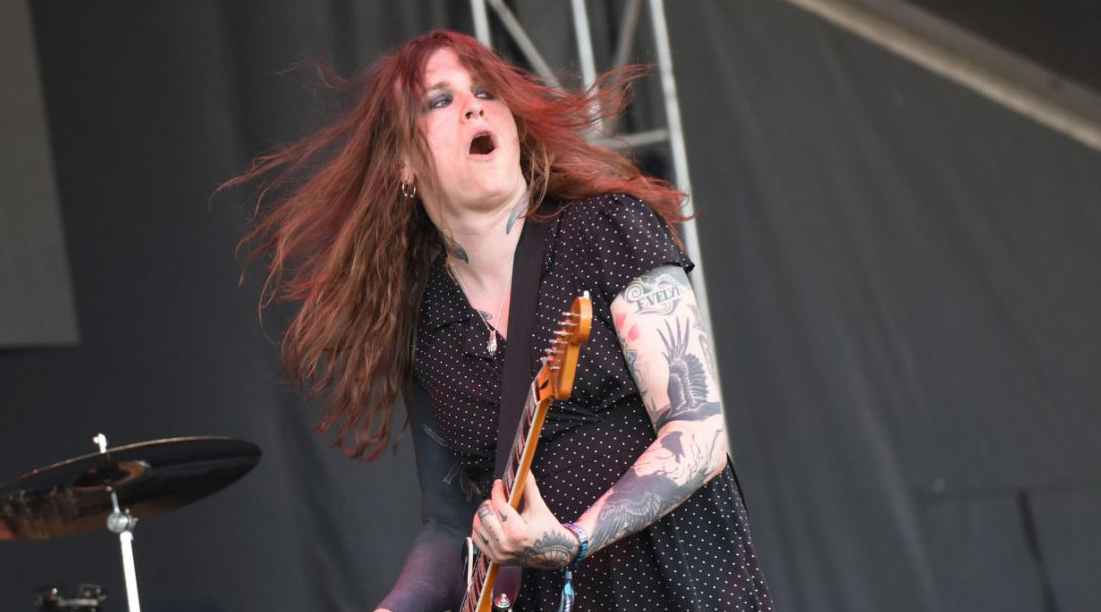

For instance, hearing a punk band perform something that isn’t about ‘chicks’ or pining after the girl you spent the summer with is refreshing and novel. This is what the trans frontwoman of Against Me!, Laura Jane Grace, offers. As someone binary, songs like ‘trans dysphoria blues’ makes for a ruminative experience. But for a trans person, it is a power track to them that is in painfully short supply.

The message is becoming so powerful that it transcends queer music for queer people; music from LGBTQ+ artists bleeds into the mainstream and drives forward progressive ideas of gender and sexuality. It helps break down the binary. These industry leaders don’t only pave the way for more queer artists behind them, but create room for straight and binary musicians to play with ideas of gender. Could Joe Talbot of IDLES – a gruff looking, middle aged, straight white guy – ever have torn apart toxic masculinity in his songs even ten years ago?

The beauty of modern queer artists is that they make music that everyone can listen to; a privilege that LGBTQ+ audiences couldn’t and cannot always enjoy with hetero/binary musicians. But for these LGBTQ+ audiences, hearing queer artists on the radio and in the charts is offering them connection. For queer listeners, the saturation of songs around heterosexual, binary relationships and/or breakups doesn’t provide that incredible feeling when a song is perfectly relatable. But what might is hearing Tyler, The Creator sing “You don’t have to hide,” in ‘Garden Shed’.

Music has been a majorly formative part of my sexual identity. It is from listening to queer artists and the personalities they emanate and ooze that I found a safe and comfortable space to question my sexuality, and certainly question my own role in perpetrating conventional gender roles. For myself, not only did ‘Same Love’ call out casual homophobia, but it also established that no one could tell me what I was. And, most importantly, it told me that I didn’t have to be queer to support queer people – a concept that, even now, people seem to struggle with.

When The Heist was released in late 2012, the album with ‘Same Love’ on it became the first CD I ever purchased.

Tom Poole

Feature Image Credit: Chris McKay