The Gryphon Features look at the prominence of fake news and the art world’s capacity to question it.

Recently one of the most prominent buzzwords in current affairs, bandied around by everybody from readers of the Guardian to angry politics students, is ‘fake news’. This is the notion that what we are being told by the media is false in order to dilute the representative zeal of the media as an irrefutable conveyer of the world’s events. Conveniently enough it’s only been alternative media stories that have been frequently subject to this outrage. This ‘fake news’ label has consistently been a label applied with substantial bias, steering clear of the papers that are supposedly ‘accepted’ and reputable institutions.

Within the art world however, the increasing blurring of distinctions between truth and fiction, particularly in relation to the media, has been a subject of several projects and exhibitions. Art’s role in the current political, sociological and general global climate is one of absolute paramount importance. I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to suggest the rapid slicing of funding for the arts, all over Europe and America, is deliberate. Creative subjects foster the ability to question the world around you and think in an individual and resistant way. Cutting off the ability to explore such subjects is the government, who are as a result stunting our ability to question and challenge them. This is why artists seem to be fervently reminding the world of their importance. From William Blake in the Romantic period to Bacon’s nihilistic and gloomy portraits, revolutionaries in the art world have never shied from being a readily available social commentary. Those with influence are reminding the world of just how blurred that line between truth and fiction is in politics.

FACT Liverpool: How Much of This is Fiction?

Ranging from 3-D printing to an exact replica of Julian Assange’s office at the Ecuadorian Embassy, David Garcia and Annet Dekker have created a space that traces this idea of ‘fake news’ a lot further back than the arrival of Donald Trump onto the political landscape. Following in the footsteps of ‘Tactical Media’, a movement that Garcia himself helped coin and theorize, ‘How Much of This is Fiction’ looks at the ways in which alternative media functions as a challenge and a critique of the readily accepted media of the establishment. Drawing on the Dada movement, the new set of works also attempts to do exactly the opposite of what its critiquing, offering up an interesting and challenging antithesis. In an interview with New Tactical Research Garcia said that ‘I hope that the exhibition opens up a degree of scepticism around current narratives and many clichés that we are living in a post-truth/post-fact world’ attempting to show that this is not a new phenomena, but a long standing symptom of the political sphere as a whole. Garcia also mentions in the interview ‘Tactical Media’, an activist tool which functions as ‘a new category that occupied a no man’s land between art media and politics’. One of the motivations for the show was to reinstate ‘the value of this cultural positioning’ claiming it ‘should be reclaimed and maintained’. Garcia’s motivation, along with his colleagues, seems to be tracing this idea of misleading media and manipulation of the public much further back than one might think. ‘Tactical Media’ shows the importance of alternative media sources and the danger of conflating them under the definition ‘fake news’.

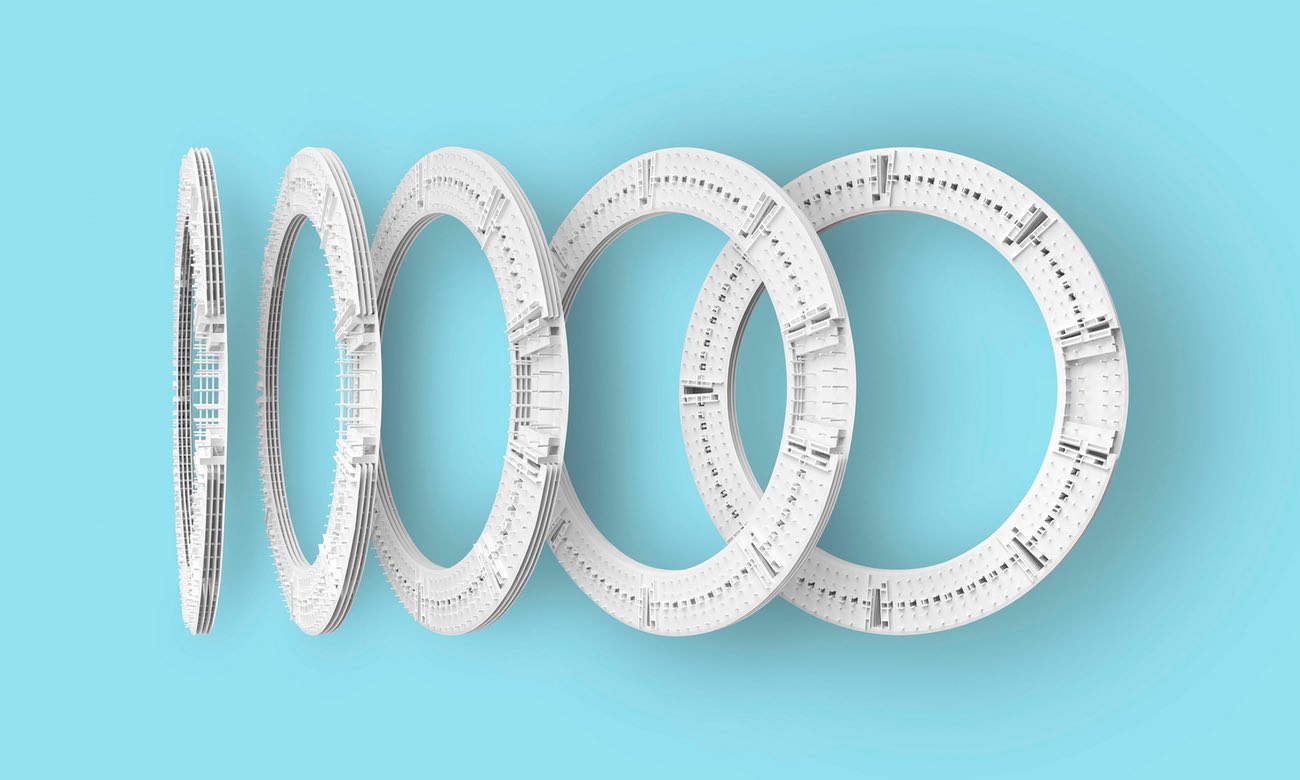

Alan Cristea Gallery: Langlands and Bell: Infinite Loop

This artist duo, now in their late fifties and sixties, have created a variety of constructions aiming to replicate and reveal the secrets of the monolith powerhouses of technological companies in Silicon Valley. Nikki Bell, in an interview with the Guardian, describes the structures as a ‘fantasy of total control’ that ‘oozes strategy, ambition, globalisation and technology; it so thoroughly embodies what these companies are about’. Though not explicitly a challenge to the mainstream media, these works nonetheless question the trust we readily give to these companies and the shocking influence and manipulation they have upon us. Having previously constructed replicas of banks in Frankfurt and the headquarters of Nato, the pair have a long history of probing and questioning the power and supposed impenetrability of such global influences. Showing the structures themselves in dissected detail, the pair seem to reveal the way in which the buildings themselves reveal their influence outside of their walls. In this way the pair seem to be exemplifying the same critique that Garcia and his team are: looking at the public versus private representations of the world’s power structures. On the surface, as Nikki states in the interview, these companies are still projecting the ‘casual start-up jeans-and-T-shirt culture’. In reality, once the surface is penetrated as it is in their work, the underbelly and messy innards of these corporations is much darker, murkier and far less happy-go-lucky than Mark Zuckerberg would have you believe.

Something seems to be happening in the art sector to remind us all of something important: the significance of our ability to question. With a wave of alternative news sites being banded together as equally fictitious, anything outside of the given mainstream will start to suffer. What both of these exhibitions cleverly reveal is the importance of what lies beneath the surface, looking at the implied rather than the explicitly outlined. Both shows use art to remind us of art’s role in shaping, questioning, challenging and often even dismantling the political landscape. In a time when art programmes and funding is being sliced almost imperceptibly thin, those with influence are here to point out the motivation for this. So perhaps, in a time when violence, war and supposedly democratic politics is abound, the best weapon to equip yourself with is a paint brush, a pencil and a brain full of questions.

Jessie Florence Jones