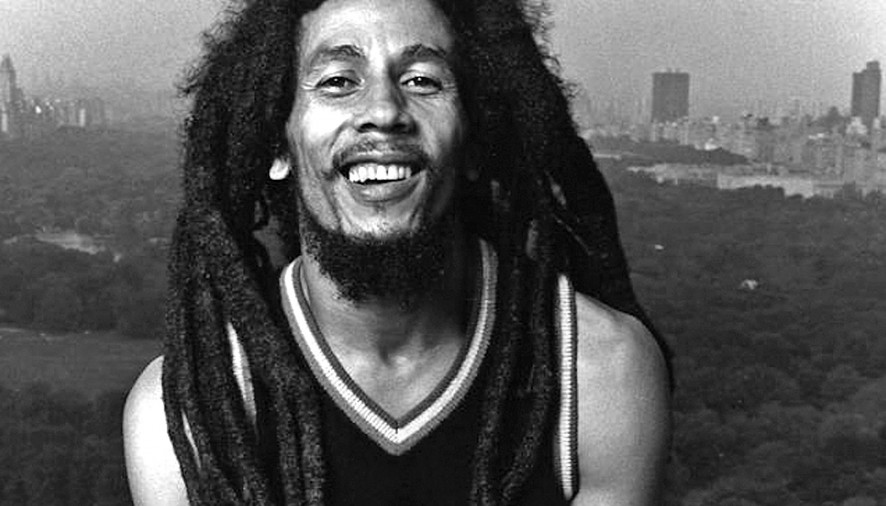

Celebrating what would have been Bob Marley’s 71st Birthday, Jemima Skala looks back over the career of the reggae icon.

Bob Marley has been so influential, throughout his life and even throughout the decades after his death. His is the name that immediately springs to mind whenever you mention ‘reggae’ or ‘rasta’. He is the touchstone for everyone looking to get into reggae and has spawned a whole cult of followers, copycats. and total admirers. His legacy has survived him, and shows no sign of fading.

His music is a point of connection for everyone, whatever your musical leanings. My dad is a huge reggae buff, and would play the most obscure reggae and dub tracks around the house whilst I was growing up, but I knew Marley’s name long before I knew Peter Tosh, Lee Scratch Perry or Bunny Wailer. I listened to Bob Marley in every guise; my favourite song for years was The Fugee’s cover of ‘No Woman, No Cry’. We even used to sing ‘One Love’ in music assemblies at primary school in lieu of the more traditional songs. A friend of mine professes to detest reggae in all its forms, because “it all sounds the same”. Aside from the fact that he is simply wrong, he concedes that the two reggae artists he will actually listen to are Desmond Dekker and Bob Marley. It speaks volumes of Marley’s ability to reach even the most dedicated rock and roller. Perhaps this was because Marley was able to express universal emotions very simply, succinctly, and in a way that would speak to the most amount of people.

Although, in the grand scheme of the reggae scene of the Caribbean in the 1970s, Bob Marley is only a thread in a rich tapestry, his position as the figurehead of the movement was never in doubt. Marley was as politically involved as he was musically active. In 1976, Michael Manley, head of the Communist-leaning People’s National Party (PNP), asked Marley to play at the free Smile Jamaica concert he had organised to relieve the tensions between the warring supporters of the PNP and the Jamaican Labour Party (JLP). In spite of declaring his support for Manley in 1972, Marley made a point of setting up an entirely neutral standpoint for his performance; he dissuaded Manley from staging the concert on the lawns of the Prime Minister’s official residence. He was infuriated when he found out that the government had coincided the concert with the elections, saying, “dem want to use me to draw crowd fe dem politricks.”

In spite of suffering an attack from armed gunmen two days before the concert, Marley still performed, justifying this with, “the people who are trying to make this world worse aren’t taking a day off. How can I?” This whole episode has become somewhat ingrained in the folklore of the Kingston ghettos, and is the subject of Marlon James’ Booker Prize-winning novel A Brief History of Seven Killings.

After this incident, Marley spent two years in England to get away from the political hotbed that Jamaica had become. 1977-1978 was spent recording Exodus and Kaya. The former remained on the British album charts for over a year consecutively. Again, we are reminded of Marley’s universal ability to speak equally to people living in the Jamaican slums and the townhouses of Kensington.

While it’s not always desirable to remember the more negative aspects of our idols, it’s important to remember them for the person they were, as well as for the influence they had. In this light, it’s difficult to remember Bob Marley without remembering his rather unattractive habit of chronic adultery. After marrying Rita Anderson in 1966, he had relationships with several other women throughout his lifetime. Rita claimed that Marley was abusive towards her at points in their relationship, both physically and emotionally. Marley’s estate recognises that Bob Marley had eleven children: three with Rita, two from Rita’s past relationships, and several others from other women. However, it is likely that there were more.

Marley converted early on in his career from Catholicism to Rastafarianism, a sect of Christianity that rejects all material and earthly pleasures, which they term Babylon, and proclaim Zion, a reference to Ethiopia, as the Promised Land. In 1970s Jamaica, Rastafarians were on the receiving end of a lot of persecution as a result of their dreadlocks, which were perceived as dirty, and their religious and ritualistic use of cannabis. Marley, however, was responsible for showcasing Rastafari music and culture on a global stage, taking it from the ghettoes of Jamaica and bringing it to the world. Whilst this may have had the cringe-worthy side effects of causing numerous young white stoners to grow dreds, Marley was responsible for the popularisation of Rasta culture.

Marley made seemingly simplistic statements speak absolute volumes. The lyric in ‘No Woman, No Cry’ of “then I’ll cook wholemeal porridge/Of which I’ll share with you” spans the mundanity of simply cooking porridge; it’s the following line that gives it meaning. Suddenly, the lyric becomes less about domestic tasks and more about the spirit of humanity. Conversely, the nonsense verses of ‘Them Belly Full (But We Hungry) have puzzled listeners for decades (what is ‘a yatta yuck’??) but the words almost don’t matter in the context of the most incredible bassline you have ever heard. It was Marley’s ability to make music speak beyond lyrics that has contributed to his dedicated following. It makes sense, therefore, that he was asked to play in Boston at the Amandla Festival in 1979 to demonstrate his opposition to the apartheid in South Africa: he could make his music speak for every person suffering under the weight of oppression.

There’s no real way to stop talking about Bob Marley. His presence was so great that it spans across a multitude of subjects, of which there are simply not enough words to cover them in the detail they deserve. In spite of his failings as a man, he was a brilliant musician: dedicated, perseverant, hardcore. He spoke for all those who could not speak for themselves, inspiring generation after generation to get up, stand up, and dance.

Jemima Skala