In 2019, Andrew Moffat, an assistant head teacher at Parkfield Community School in Birmingham, created the ‘No Outsiders’ project – an initiative designed to teach his pupils about the 2010 Equality Act and encourage them to “be proud of who they are while recognising and celebrating difference and diversity”.

However Moffat’s good intentions were quickly thwarted. For months, mobs of angry parents took to the streets claiming that a relationships education which was LGBT-inclusive contradicted their Islamic faith and was not “age appropriate”. The school unwittingly found itself at the centre of a very public protest scandal, that was ultimately quelled by a High Court ruling banning the protestors from demonstrating on school premises. Yet Birmingham City Council maintained that the legal action was taken solely on the grounds of the campaigners’ disruptive behaviour, rather than the issues and content of the protests themselves.

The events that took place in Birmingham in 2019 raise an interesting question. Should the curriculum solely concern itself with Shakespeare and sin functions? Or should it be serving a broader purpose; to equip children with the kinds of skills and knowledge that they will actually need in the ‘real world’? And, crucially in this case, to what extent does agreement with the latter infringe on the rights of parents to dictate their childrens’ moral and ethical beliefs?

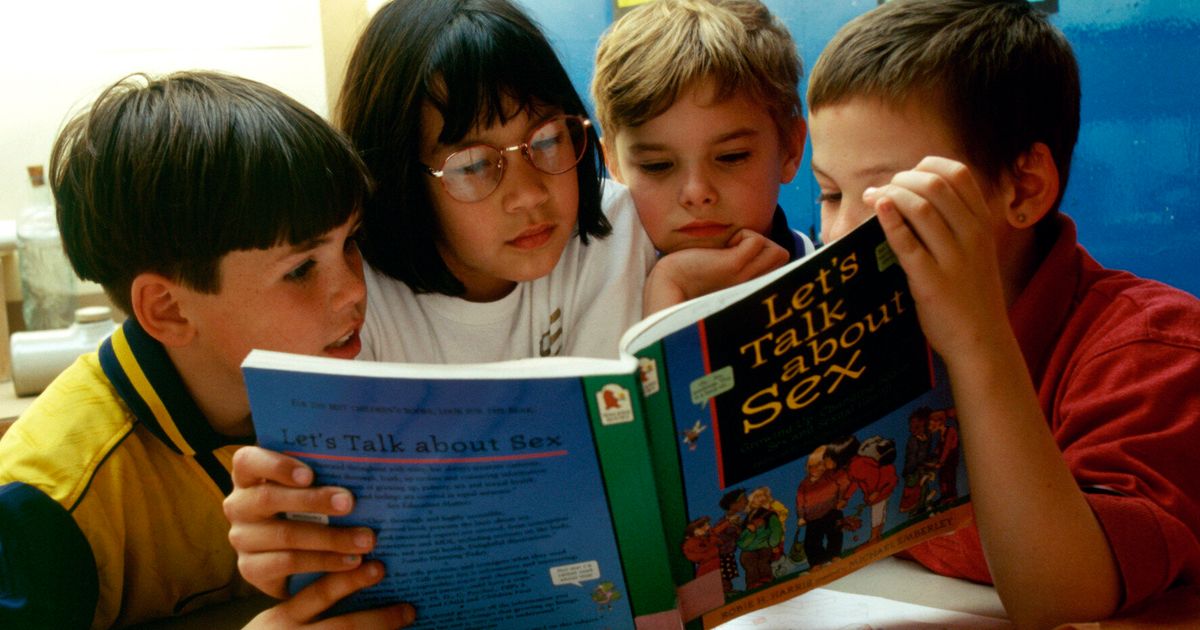

Personal, sexual, health and economic (PSHE) education has historically been under-valued and under-resourced in schools in this country. The memories I have of PSHE lessons, ones I think are emblematic of many others’, are sparse and underwhelming. Pouring a Capri-Sun over a tampon with my girlfriends to see if it would hold (naturally, whilst our males peers were quarantined elsewhere), although hilarious, did little to equip me for the complex reality of actually having a menstrual cycle. Nor did trying to fit a condom over a banana in secondary school failed to educate me on the nuances of sex, contraception, relationships and consent in any meaningful way.

The result of PSHE lessons not being given the respect and air-time they deserve, is that the knowledge of children and young people in such matters can be immensely variable. Although I came out of the education system with some nice grades and a University offer, I was altogether naïve about anything remotely useful when it came to actually operating as a young person in the ‘real-world’. Whilst I had the blessing of being landed with older and wiser flatmates in first-year to thank for my sexual health education, many others are not so lucky, and the results of this can be extremely damaging.

In recent months, shocking allegations against secondary institutions across the UK have come to light with the launch of ‘Everyone’s Invited’ – a website aimed at exposing rape culture through ‘conversation, education and support’. The site offers a platform for individuals to post anonymous accounts of misogyny, harassment and assault and, in the wake of Sarah Everard’s tragic death in March of this year, pupils have been posting testimonies in their thousands. Although some of the posts have come from boys, the majority are tales of sexual harassment carried out against young women by male peers at their school or university. The revelations have prompted outcry about the toxic ‘rape culture’ that appears to have permeated our educational institutions.

Ironically, the origins of such a culture could partly lie in the approach to teaching in the very institutions it pervades. If schools were teaching comprehensive, age-appropriate and well-delivered sex and relationships education, this might go some way to improving attitudes towards consent amongst the young boys and men carrying out the harassment detailed in these testimonies. In its absence, the message is that such matters are not important.

In addition to the patchiness of sex, health and relationships education, financial literacy is another gap that has long been glaring in school curriculums. Although financial literacy has actually been part of the National Curriculum since 2014, recent polling found that just 8% of young people said they learned the most about money skills in school. The result of this is, again, vast discrepancies in how well-equipped young people are to manage their personal finances in the future, and how much they appreciate the importance of doing so.

More worryingly still, is that financial literacy is highly interwoven with privilege, meaning that this disparity often runs down the fault line of class. My – admittedly limited – knowledge of saving, interest rates, shares and mortgages is entirely attributable to the relative advantage of my upbringing and the good fortune of having a parent who watches financial asset performance vlogs as a hobby. For families whose sole focus is making their budget last until the end of the week, such matters are a luxury they cannot afford to prioritise.

The UK government does appear to have somewhat woken up to the significance of these problems; having recently updated the statutory guidance on PSHE education in 2019. Relationships and health education are now compulsory in all primary schools, and ‘relationships and sex’ education is mandatory in secondary schools. The new guidance also reinforces the importance of the teaching of issues ranging from wellbeing, mental health, healthy relationships and internet safety.

Although the new curriculum was due to come into force in September 2020, schools have been given an additional 12 months to turn plans around in light of the pandemic, so it remains to be seen how transformative the proposed changes will really be in practise. There is also the inescapable problem that the effectiveness of these lessons will always be primarily at the discretion of individual schools and teachers and how well they actually deliver them.

A broader culture of acceptance is vital too – and the lesson of the Birmingham protests is that this is not something that is easily achieved. Although the events at Parkfield Community School were extreme, they represent a friction that exists between parents and teachers – the two main sources of ‘education’ in a child’s life. The question of whether ‘real life’ teaching should occur in the classroom, and to what extent this infringes on the rights of parents to take responsibility for it themselves, is not one with an easy answer.

The purpose of schools is to teach. Yet, the rigidity of our schooling system has created a culture where grades are valued more highly than equipping children with ‘real world’ skills. This priority system creates all manner of problems. Despite the valid claim that parents have over shaping their childrens’ belief system, when the consequences are so severe, it does appear that a greater balancing act needs to be achieved.

Image credit: Huffington Post UK