“As the epidemic [HIV] evolves further, rates will continue to rise in communities and nations where poverty, social inequalities, and weak health infrastructures facilitate spread of the virus” – UNAIDS.

What UNAIDS said here in 1999 is still incredibly relevant today. HIV’s impact continues to be felt most heavily in areas with limited healthcare resources, a merciless symptom of global inequality.

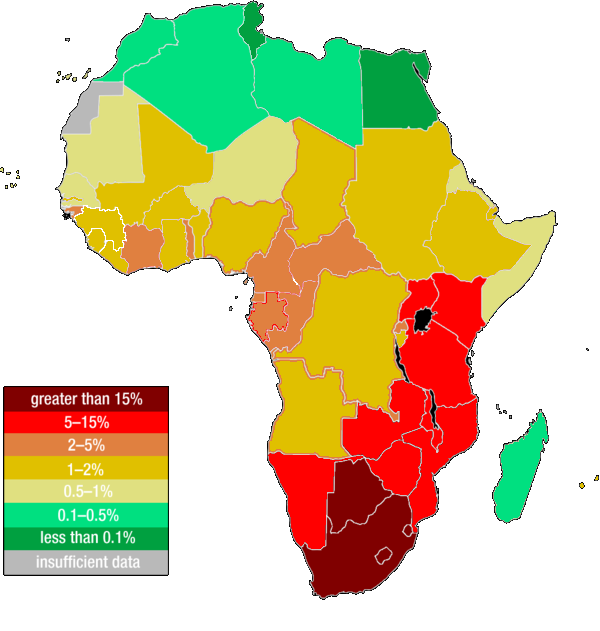

In 1959, a sailor from Manchester became the first person to live and die from what we now know as HIV. Presently, 38 million people are living with the lethal virus, which destroys the immune system if left untreated. Ultimately, this has led to over 32 million deaths across the world. It is important to understand – particularly in a world where discourse would suggest there is just one health crisis raging – that HIV has had a huge impact, particularly in economically developing countries where 95% of the present HIV cases have originated.

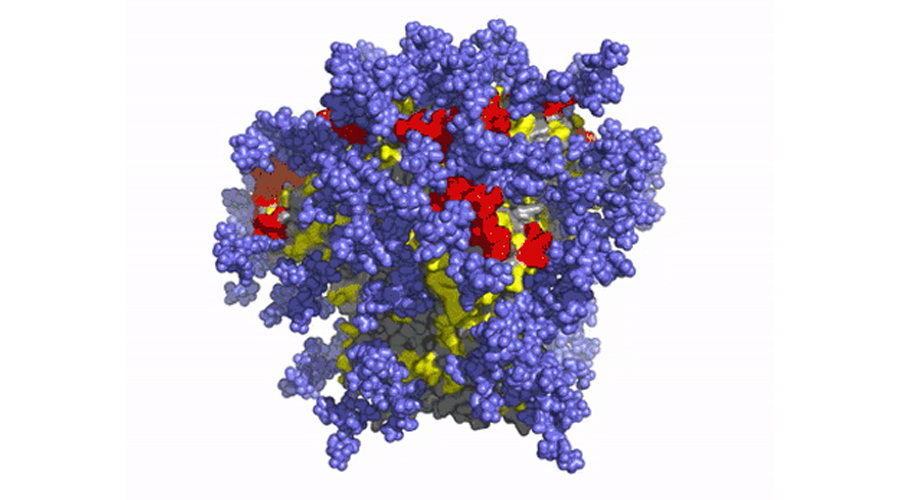

It seems, however, that progress is being made in the pursuit of a vaccine against HIV. Over forty years since the current HIV epidemic began, scientists at AIVI and Scripps Research revealed the results of their phase 1 clinical vaccine trials. This data showed that, in 97% of recipients, the proposed vaccine stimulated the immune system to produce rare immunoglobulin G (IgG) B cells, which form antibodies against HIV.

This is very exciting news. HIV is notoriously complex as it has a huge number of different strains. As William Haseltine put it, “HIV continually evolves – a shrewd opponent seeking ways to elude our immune responses”. This has made the search to find an effective protein to base the vaccination on difficult, because different strains have different protein compositions. It has therefore been necessary to find a protein which is present in all the strains in order to defend against HIV in all its forms.

Why do we need a vaccine?

Finding an HIV vaccine is of imperative importance. Whilst PrEP (antiretroviral treatment) is capable of reducing a person’s viral load to imperceptible levels, this treatment is expensive and inaccessible for many who need it. In the UK, PrEP is given out by the NHS which makes our population significantly more privileged than elsewhere. For instance, only 11% of people living with HIV in northern Africa have access to antiretroviral therapy. Without treatment, HIV is a deadly virus.

The virus works by attacking the immune system; entering and replicating within CD4 cells. These are white blood cells which play an essential role in combating infection. When the cells are killed by HIV, the body loses its ability to identify and respond to other infections. At a certain point in this process HIV becomes AIDS. The proposed vaccine would work by destroying HIV before it enters the immune cells, through initiating the production of antibodies to fight the virus.

This year, many countries around the world have seen more HIV deaths than Covid deaths. That the crisis is still not referred to as a pandemic by the WHO seems very bizarre. They continue to refer to HIV as a collection of epidemics, despite its geographic prolificity. Whilst semantics isn’t everything, this contemplation of HIV is concordant with the disparate way it has been tackled from a healthcare perspective: some countries have efficient and widespread treatment available for HIV. Other areas have failed to supply HIV positive people with medication. The issue with failing to acknowledge that HIV is a worldwide problem is that it enshrines the responsibility for tackling outbreaks solely with the country in question, negating the need for international coordination.

This is why a vaccine is so important: not only could it greatly reduce HIV figures, it could also lead to a cohesive worldwide approach to HIV. Reducing the demand for highly costly treatment could lessen the destructive and circular impact of HIV on communities.

Why has this taken so long?

Another point of contention has been the fact that this proposed vaccine has taken almost 40 years, when the Covid vaccine was found so quickly. Has the stigma surrounding HIV held up the vaccine process? Has the marginalisation of LGBTQ+ communities slowed down the hunt for this?

Ted Ker offers an interesting insight: “The impact of the near-pathological focusing on gay men when it comes to the virus had implications beyond the scope of representation”, he says. “Before 1993, there was no official government definition of AIDS that included many of the people most impacted by the epidemic”. For instance, the fact that HIV could be passed on through heterosexual sex and needle usage took a long time to be acknowledged. This illustrates the way in which public stigmatisation and misinformation formed a gauze around HIV, impacting public understanding of preventative and therapeutic measures. Whether or not the stigma surrounding the virus impacted the quality of research is a question of theoreticals, though it is definitely a question deserving of investigation.

However, from a medical perspective, vaccines often take a long time to find. HIV has posed particular problems due to its unique and multifaceted nature. Most vaccines work by priming the immune system to recognise and fight infection. However, no one naturally recovers from infection with HIV, so the search has been for an antibody that can kill the virus before it enters the immune system. There have been many unsuccessful vaccine trials in the past, such as the RV144 trial in Thailand in 2009. This trial had more than 16,000 participants and took over six years to complete. Whilst the proposed vaccine had 31% efficacy against HIV, this was not deemed sufficient to adopt the vaccine outside of its trial context.

The present trialled vaccine is a source of hope, but still has a long path ahead of it. “A holy grail of the HIV vaccine field is to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies by vaccination, and here we’ve shown in humans that we can start that process,” said Professor Schief at a virtual conference of the International AIDS Society HIV Research for Prevention on February 3, 2021.

However, there is still a way to go. This trial was small and follow up trials will be necessary. The researchers are hopeful that partnering with Moderna (creators of the Moderna Covid-19 vaccine) and using their mRNA technology will help them see the same safety and efficiency in their HIV vaccine.

By Amy Ramswell

Header image from EPM.