In light of the recent Hartlepool by-election result, Alex Howe analyses why the Labour party is losing support.

In the United Kingdom it is rare for an incumbent government to win a by-election at all. It is rarer still for a government to win a by-election in a seat that it has not held since its creation over half a century ago. However, this is exactly what happened on Thursday night, when the constituents of Hartlepool elected a Conservative MP for the first time in history.

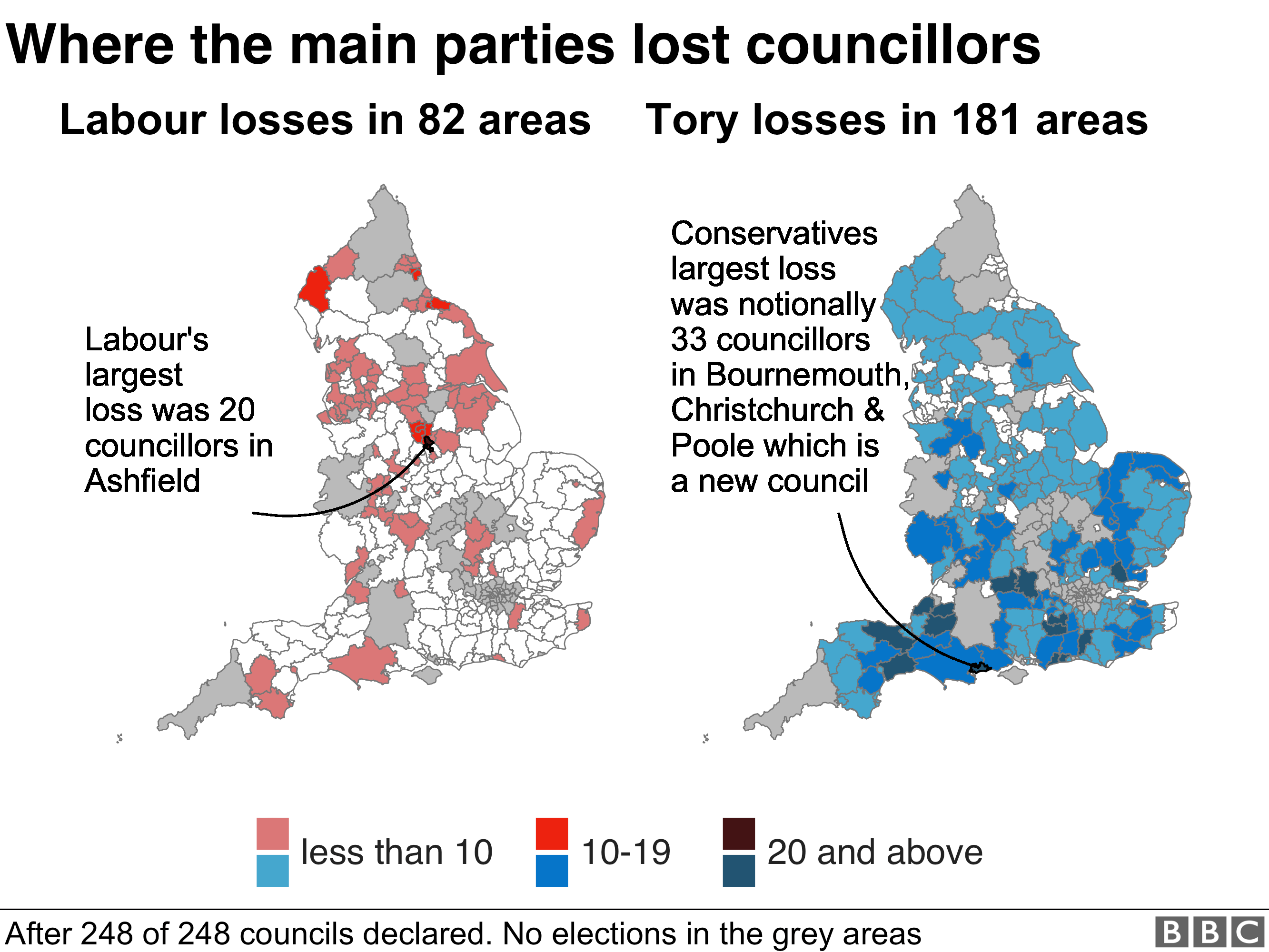

The result was utterly decisive, with the Tory candidate Jill Mortimer winning almost twice as many votes as Labour’s Paul Williams. Hartlepool is of course one of the seats in what was formerly dubbed the “Red Wall”, which collapsed following Labour’s catastrophic performance in the 2019 general election. A similar story unfolded in the local elections around the country, in which the Conservatives continued to make gains in previous Labour heartlands even despite the recent accusations of sleaze, as well as a general response to COVID-19 that many have labelled appalling.

With Keir Starmer’s election as party leader, Labour heralded the dawn of a new era which was intended to revitalise the party after the nadir of Jeremy Corbyn’s final months in power. However, what Hartlepool demonstrates is that Labour still has an extremely long way to go if it ever wishes to govern Britain again. Labour MP Khalid Mahmood, who resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in the wake of the local election results, outlined what many in the political landscape outside of Labour had already realised. Problems that many party members believed to be the result of the leftward swing under Corbyn, and could be resolved with a change of leadership, have been thoroughly exposed for how deeply entrenched within the party they are.

The first issue is clear. Labour, a party which was formed in order to represent the voice of the working class, has lost its support entirely. This was evident in the wake of the results of December 2019, which saw voters in Red Wall seats such as Sedgefield and Bishop Auckland reject the party entirely in favour of lending their vote to Boris Johnson’s Tories. Hartlepool itself was arguably only saved from the same fate by way of a large turnout in favour of the Brexit Party, which split the right-wing vote and allowed Labour to retain the seat. With the Brexit Party’s mandate complete, the way has been paved for the Conservatives to swoop in.

What many political commentators have argued is that the decline in working class support is down to two factors; the politics of Labour under Corbyn, and Brexit. Yet, while these issues have accelerated the trend, the gradual slide in support from the working to the middle classes has been happening since the era of Tony Blair. In the 1997 general election, for example, Labour increased their support to 39% from managers and administrators. Their embrace of high university attendance, mass immigration and the market economy were just a few of the policies that while allowing them to steal swing voters from the Conservatives, also sparked the party’s alienation from the working class.

The difference, however, is that Blair could appeal to the centre ground, whereas Jeremy Corbyn never could or wished to do so. While Blair embraced economic liberalism, Corbyn shunned the free market. But the divide in economic opinion has been replaced since the 2010s by a stark conflict between socio-cultural values. Under Corbyn, Labour’s leftward swing towards Neo-Marxist identity politics became popular with more radical sections of the populace, such as young left-wing graduates and revolutionary socialists, but also attracted a considerable following from socially liberal, city-dwelling middle classes, primarily in London. Corbyn promised a society “for the many, not the few” but his party’s indulgence of fringe ideologies, as well as his own dealings with members of extremist groups such as Hamas and the IRA, demonstrated that the working class were no longer a priority for Labour and only served to further disillusion their old voters.

The 2019 election laid bare the state of Labour’s new support base. While still retaining several historically safe seats in places such as Merseyside and the North East, the red spots in the now overwhelming blue of the country have shifted from the northern heartlands to affluent London locations like Islington and the City, or heavily student-populated constituencies such as Cardiff Central, Exeter or Oxford East. Salford and Preston, two of the few northern local councils in which Labour made gains this year, are student towns. And even Sadiq Khan, who remains relatively popular in London, retained his position as Mayor on a reduced vote.

And we must of course examine the issue of Brexit. 17.4 million people voted to leave the European Union in June 2016, of which a great many were from working class towns such as Hartlepool. It is perhaps the single most significant act of direct democracy for generations. Yet, the next three years of political machinations saw many prominent politicians attempt to reverse it. No party can be blamed for this more than Labour. The once prominent Eurosceptic Jeremy Corbyn and arch-Remainer Keir Starmer constantly seemed unsure of where they stood during these intervening years, finally half-heartedly committing to a “People’s Vote” in 2019. By contrast, while under Theresa May the Conservatives looked set to tear themselves apart over Brexit, under Boris Johnson they committed to securing the UK’s departure from the EU, leading those who voted to Leave in 2016 to turn out for them in droves.

What is more, from the selection of Paul Williams as the by-election candidate, it is clear that 2019 was not enough for Labour to learn from their mistakes. Williams, a Remainer, was turfed out of his previous constituency Stockton South in 2019 after defying the party whip six times to vote for a second referendum. 62% of Stockton voters voted Leave, as did almost 70% of those in Hartlepool. Williams’ record, along with his previous ill-judged comments towards the Brexit voters he claimed to represent, arguably sum up his unsuitability for the seat of Hartlepool.

It is the relationship between the party and the Brexit-backing demographic that is key to understanding the demise of the Labour Party. As Paul Embery states in his acclaimed book Despised, over the last few years Labour have consistently failed to recognise the wants and needs of what was once their core electorate. On Twitter and even in Parliament, it is now commonplace to hear Brexit voters being labelled as either ill-informed or xenophobic by members of the very party that seeks to win their vote. Aside from the smaller and more socially conservative Blue Labour, there is not a faction of the party that has truly succeeded in accepting the result of the referendum.

Thus, Labour is now dominated by two groups, both of whom often do a better job of fighting with each other than they do of providing an effective opposition to the Conservatives; the Corbyn-backing socialist left, characterised by highly ideologically driven groups such as Momentum, and the moderate but overwhelmingly pro-EU centre-left who the Corbynistas simply view as Tory-lite. The former are too dogmatic to compromise with the rest of their party, exemplified by recent comments made by the likes of Diane Abbott and Owen Jones who have blamed this week’s poor performance on the absence of Corbynism. Meanwhile, the latter are simply not powerful enough to dominate the far-left threat and offer themselves as a competent alternative to the government. Rather than self-reflection, both tend towards throwing accusations of racism at those who take their vote elsewhere. Both sides are in denial, both are currently unelectable, and both appear to look upon the masses with little more than contempt.

It is testament to the mess that Labour is in that it has been unable to mount a serious challenge against a government that has not only spent the last few weeks under a cloud of corruption, but come under fire from all sides for their response to the pandemic. Therefore, it is not simply a case of a new leader or a new manifesto that will help Labour on the road to electability again. It looks as though they will not be able to beat the Tories again for a long time, and it appears far more likely that the party will collapse rather than recover from near-electoral obscurity.

The Labour Party can no longer blame the electoral system, the vaccine bounce, the delays caused by COVID-19, Russian conspiracies, or the alleged bigotry of the working class, on its failings. If they are even to become a viable opposition again, Labour needs a radical overhaul of its values, a complete purge of its culture of extremist elitism, a genuine embrace of moderate social democracy, and above all, an overt demonstration that it cares for the country it wishes to govern.

Header image credit: The Spectator Australia