‘Girls supporting girls’ proclaims a PrettyLittleThing t-shirt, while another from BooHoo keeps it simple with just ‘International Women’s Day’ on the front in cute pink letters. The proceeds of the former even go to GirlsInc: an organisation that empowers girls facing economic and social barriers through mentoring relationships. However, it is not very ‘girls supporting girls’ when the hands who make these t-shirts face unsafe and dangerous working conditions.

According to the Open Society Foundation, approximately 80% of those in fast fashion factories are women and of these most are women of colour living outside the US and UK. For a poverty-level wage, they work in what Anannya Bhattacharjee of the Asia Floor Wage Alliance describes as “inhumane“ factories, where there is a “norm“ of gender-based violence. Wage theft and a lack of health and childcare are commonplace. PrettyLittleThing’s own labour rating is “very poor“ according to the Good On You directory, and its Fashion Transparency Index of 0-10% starts to make sense given the lack of information that they supply in terms of their supply chain. Are those tops looking so feminist now?

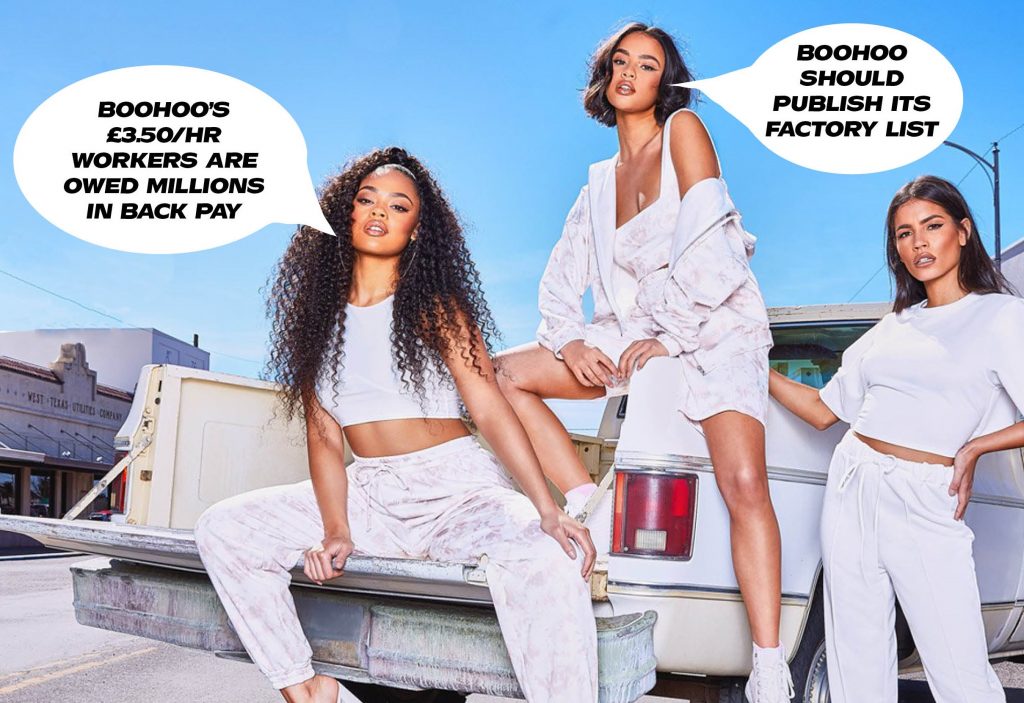

BooHoo, which owns PLT, doesn’t do much better. In the first lockdown, they were found to be paying factory staff in Leicester below the minimum wage. They have since denied any wrongdoing, claiming to have been unaware their clothes were being manufactured there. But if companies don’t know what conditions their clothes are being made in, how can they be held accountable? And without accountability, how will this ever change? Besides, it doesn’t take a brainiac to realise that maybe there is something not quite right about an 8p black dress from PLT in the Black Friday sale or BooHoo’s £3 ‘International Women’s Day’ t-shirt.

COVID-19 has unsurprisingly worsened the situation for these mostly female workers, as Global Labour Justice reported, with gender-based violence increasing in the workplace. In May, PLT orders jumped from an average of 120,000 shipments a week to 400,000, just as workers needed more space, more time and more safety. PLT continued its policy of non-disclosure and still has yet to lay out what it has been doing for its labour force abroad in these challenging and dangerous circumstances.

While donations to charity and the promotion of International Women’s Day are welcome, when it comes from fast fashion brands – whose very existence relies on the forced labour of women – it can leave a bitter taste in the mouth. The lip service they are paying to this day, rather than actually helping and aiding the women that work for them, displays the hollowness behind their consumerist approach. As BooHoo expands, seen in its purchase of Nasty Gal, these work practices are going to continue as their success displays how it clearly ‘pays off’. Again, white feminism is shown to be lacking: the middle-class Europeans and American women who purchase these items remain unaware of the damage their relationship with fast fashion causes. But, after all, what can you expect from a brand whose very name denotes the objectification and infantilisation of women?

Header image: Pretty Little Thing