Trigger warning: sexual assault, violence.

Whilst in the midst of tackling the Covid-19 pandemic, we are simultaneously experiencing another “global health problem of epidemic proportions” according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Director-General Dr Margaret Chan. The difference is the second global health problem has been raging for millennia and there’s no miracle vaccine rollout insight. The epidemic? Violence against women.

In the wake of Sarah Everard’s disappearance and subsequent murder, many disheartening statistics have come to light. WHO has found that “1 in 3 women globally experience violence”, whilst YouGov polling revealed that 97% of young women aged between 18-24 had experienced sexual harassment. And this doesn’t account for the disparity of experience for BAME, LGBTQ+, or disabled women. One thing is clear: The statistics and data demonstrate that this is undoubtedly a gendered issue that skews decisively towards women who bear the brunt of victimhood. Women are disproportionately likely to experience some form of harassment, almost always at the hands of cisgender men.

Whilst eagerly awaiting the return of Sex Education (featuring University of Leeds’s very own Emma Mackey) many of us are still ruminating on that standout plotline of season 2 that boldly commanded our attention and spoke to the personal experience of most – if not all – women.

A detention task (invoked by the slut-shaming of Miss Sands) has the women of the series question what unites them. Initial suggestions include fantasy gaming, cosplay, shopping and chocolate but none seem to hit the mark. Ultimately, the revelation that not a lot unites the women “other than non-consensual penises” provokes the unravelling of each woman’s individual experience of harassment. The quip delivered by Simone Ashley is a moment of relief for viewers – a light-hearted breath of humour to alleviate (without negating) the gravity of the serious discussions surrounding violence against women. The scene of solidarity amongst and between women raises important questions of bodily autonomy and restricted freedom that so many of us face.

The ongoing, horrendous story of Sarah Everard has gripped the UK as a culmination of gendered violence that resonates with fellow women. Unfortunately, her disappearance, despite being emotive and visceral, isn’t surprising. For women across the country, fear for our personal safety is at the forefront of our consciousness every single day. For most, it has been drilled into us for so long that it has become a ‘normal’ routine to implement precautions and strategies to protect ourselves. In conversations about sexual harassment, most women will be able to list the precautions they take daily: not going out after dark, not walking alone, sharing locations with friends, avoiding dark and badly lit roads, crossing the street to avoid unwanted interactions, taking detours to avoid being followed, carrying keys in our hands, not listening to music, not dressing ‘provocatively’ and watching our drinks to name a few.

Our lives centre around keeping ourselves safe in spaces where we shouldn’t have to fear for our lives. Women (and other marginalised groups) had already been living under restrictions before 2020. What was ‘normal’ to us was a novel experience for the rest of the population. Perhaps that’s why studies have shown that women are more likely to adhere to coronavirus restrictions – because we’re used to our freedoms being curbed. This is simply an extension of a reality we already existed in and, unlike everyone else, those restrictions won’t be magically lifted as coronavirus subsides.

Whether you’re aware of it or not, women have been conditioned from an early age to avoid and deflect. We’re taught to nervously smile when strange men stand too close and perfect the art of smiling enough to not be called a bitch but not so much as to invite further unwanted contact. So ingrained are these practices that for most of us they’ve become ‘normal’. It’s not normal. The caring friend who says “let me know when you’re home!” has a cheery veneer but fails to mask the dark undertones of the words that are left unsaid. The words that are silently acknowledged and understood by all women, but are better left lingering in the imagination. Because we all know what fills in the blank of the trailing ellipses. “Let me know when you’re home”… so I know you’re safe. So I know you haven’t been raped. So I know you weren’t followed. So I know you’ve not been attacked. So I know you’re not dead.

Women have long been burdened with the responsibility of preventing violence against themselves. All the actions we take perpetuate the shifting of responsibility away from perpetrators and onto victims. Violence against women seems to be the only crime where the victim can legitimately be asked why they didn’t do more to prevent it happening. I don’t think any victim of burglary has ever been told that they were “asking for it” because they were stupid enough to accumulate material possessions, or that they should have taken more care to protect themselves. It’s not a discussion that is entertained because of its sheer absurdity.

As a society we don’t blame the person who has been burgled, so why do we blame women who are assaulted and place the impetus for crime reduction on them? It would be absurd to suggest that someone would want to be burgled. Yet, when women’s bodies are infringed upon it’s socially acceptable to question whether they were ‘inviting’ an attack by being out alone at night as if being outside beyond sundown is a legitimate reason for a person to be attacked, and as though women begging to be allowed to feel safe on their walk home is such an outrageously audacious demand.

The response to an attack on a cisgender man would never involve the question, “why was he out alone at night?” In case it isn’t blatantly clear: No woman wants to be assaulted. It is simply not good enough to make women’s safety contingent upon self-implemented precautions. Telling women to avoid going out alone (as the Met Police did in the Clapham Common area of Sarah’s disappearance) highlights a dangerous discourse perpetuating victim-blaming. Place the blame on perpetrators. Not victims.

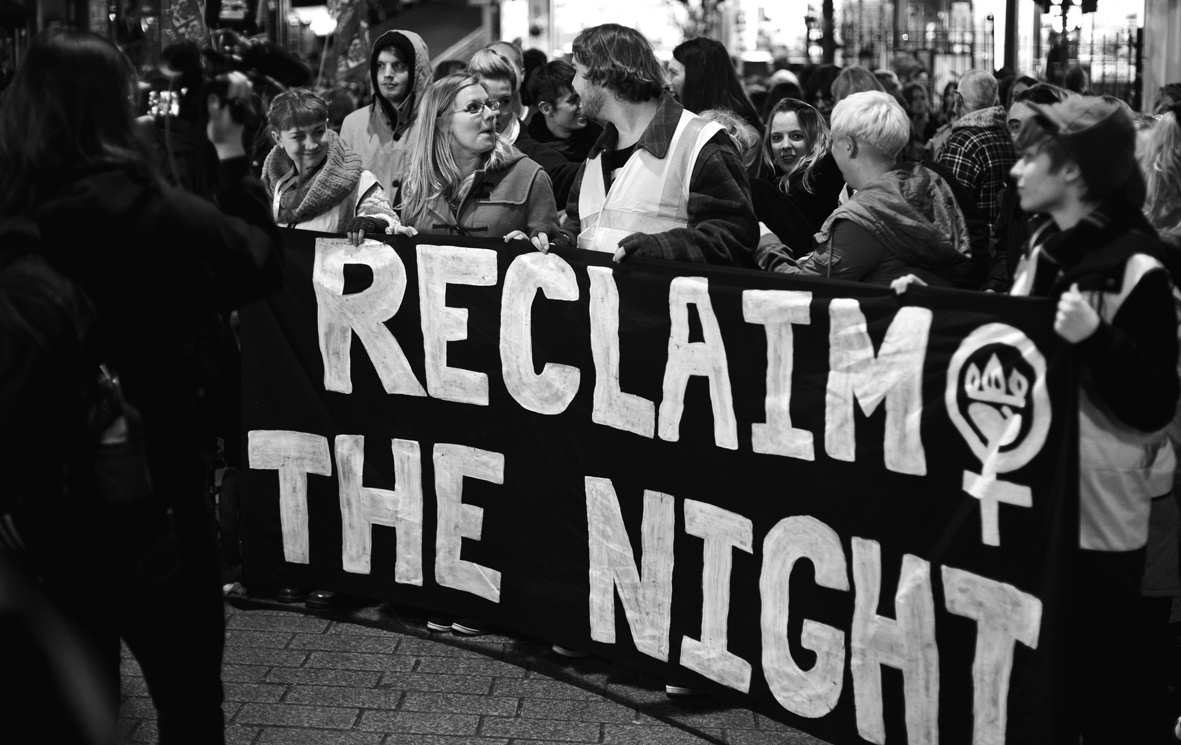

Within Leeds, the Headingley Alley has gained notoriety as an “assault hotspot” to be avoided, with activists calling for it to be closed for concerns about its safety. The Reclaim the Night movement was formed in Leeds in 1977 and served as a powerful rebuttal of the inequality women were subjected to, demanding liberation for women and their safety in public spaces. The issues we encounter in 2021 bear eerie resemblances to those of the 1970s – a time when the Yorkshire Ripper plagued the streets of Leeds and surrounding areas. The fear has persisted into the modern-day. What was seen as an issue of the past remains prominent today. Sarah Everard was simply walking home when she disappeared. She took all the recommended precautions and it still didn’t prevent her murder. Public spaces simply are not conducive to women’s safety. For too long women have carried the burden of crimes which they are the victims of. The women of 1970s Leeds were essentially placed under a curfew after police recommended that they avoid being in public spaces after dark whilst men could roam unrestricted. 40 years on, the women of Clapham Common have likewise been told to avoid going out at night and once again, Reclaim the Streets movements have been ignited.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”. Becoming a woman unavoidably encapsulates the struggle to assimilate safety and freedom. We are not born into the challenges and difficulties of being a woman, rather we live in a society that enables these horrendous difficulties to persist. This is particularly apparent when a serving police officer is the prime suspect in Sarah’s murder. All the women in your life will have their own experiences as the pervasive nature of this issue means we all have a personal story. The ongoing testimonies of thousands of victim demonstrate the need for change whereby women are no longer held accountable for the crimes they are victims of. For many, the stakes are incredibly high. As in Sarah Everard’s case, it can cost us our lives.

Kathleen Bennett

Image source: Wikimedia Commons