Delving into iPhone Notes Poetry is a bit like going down a rabbit hole littered with persistent f*ck boy word vomit, Gabbie Hanna’s crimes against literature (see: Adultolescence), and some genuinely actually quite good stuff.

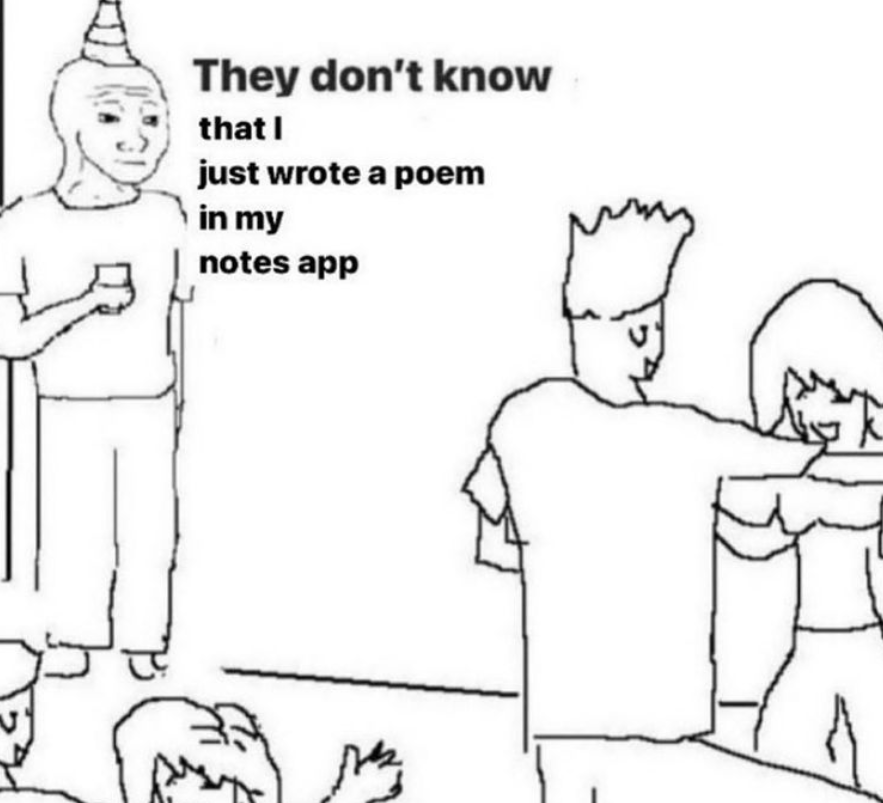

Many of us have, at some point, written an iPhone poem. Jumbled in amongst shopping lists, budgeting, reminders and recommendations can be jumbled paragraphs of incoherency, mini epics, and simply things we think sound nice. iPhone poetry is, perhaps, a matter of practicality. The Notes app might just be the modern counterpart to the writer’s notebook. And, like these notebooks, many Notes poems never see the light of day. If they do, it feels especially revealing – there is the double pronged shame of admitting, firstly, that you write poetry and, secondly, that you write it on your phone. Let it be said, some Notes poetry is genuinely horrible. I’ll be the first to admit my mortification at looking back at something I thought was profound for two minutes once.

However, one of the great merits of Notes poems is that they lack the intensity of a more formally written poem. As a writer, the fact that they will probably never be seen allows you to be more forgiving about your writing. It can be fun to write poetically without feeling you have to adhere to the conventions of supposedly “proper” poetry, and with the proviso that it need never be read again.

Notes-style poems do, occasionally, reach a public audience and can have a mixed reception. Rupi Kaur, known for her Instagram poetry and subsequent books “Milk and Honey” and “The Sun and her Flowers” where she writes candidly about matters such as love, grief, and self identity, is perhaps one of the most famous examples of an iPhone Notes/Instagram poet. Kaur has been influential in disproving poetry as a stuffy discipline belonging to the musty, staling GCSE syllabuses we all move away from as soon as possible by showing that anybody can type a poem (often short form) and publish it to an audience. However, Kaur’s work has also been met with the criticism that it isn’t “proper” poetry”. This argument, quick to assert alleged values of poetry, is thinly-veiled gatekeeping. The assumption that a poem will be bad because it comes from a more casual place than pen and ink discredits the values of Notes poetry. It is just a different type of poetry – and one that is often more encouraging and palatable.

That said, some Notes poetry should never have been published. The fact that you have to pay to read Gabbie Hanna’s “Link in bio” – in which the poem’s words are, simply, “link in bio” – does well to undermine the qualities of Notes poetry. Equally, some of us just don’t want to read weird, pseudo-romantic pick-up lines masquerading as someone’s tortured art or whatever.

Again, though, I would argue that the great joy of notes poetry is its casualness. Its accessible form, and undemanding lifespan (being written, before being consigned to a jumble in a folder) creates the perfect excuse to just write something down, mull it over, and have a bit of fun with it. Although you could elaborate a notes poem into a more formal poem, or cherry pick some words and turns of phrase you like, you don’t need to show it to anybody or scrutinise it. It can be as waffly, and weird, and falsely profound as you like – but you do wish Hanna hadn’t tried the last one. If you do want to publish it, it can be, like Kaur’s poetry, fulfilling for both the poet and audience.

It’s fun to feel a bit profound in your notes. And honestly, if most of us aren’t exactly fond of the Wordsworth Michael Gove bludgeoned us with when we were 14, Notes poetry is definitely just as valid, and more palatable than so called “proper” poetry.

Photo credit: Trista Mateer