In March last year, the government’s decision to cancel GCSE and A-level exams cast a looming uncertainty over UK students – how would grades be awarded? Would qualifications be awarded at all? Whilst 2020 students did receive valid GCSE and A-level qualifications in August, many were left feeling cheated and disappointed by their results, and more specifically by how they were determined. As a result, the Department of Education has decided to allow teachers to seal the fates of their students in 2021.

On 10 August and 12 August, for A-level and for GCSE students respectively, students will receive results based on the opinions of their teachers. These grades will be influenced by students’ coursework, mock grades, class performance and essays.

School minister, Nick Gibb, has declared that this system will be ‘consistent and fair’.

Without knowing the context of last year’s chaos, the choice to allow teachers to choose their students’ grades is naturally something to be sceptical about, considering that GCSE and A-Level are traditionally awarded based on a student’s performance in their summer exams. However, The Universities and Colleges Admissions Service revealed that on A Level results day 15,000 students across the country wrongly missed out on their first-choice university last year as a direct result of The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation’s (Ofqual) algorithm. Although they did end up receiving their offers after a Government U-turn, it comes as no surprise that the government are keen not to change methods on student assessment.

What was the Ofqual algorithm and why is it not being used this year?

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020 the government decided that it would be unfair for students to sit A-Level and GCSE examinations, and so the Ofqual algorithm was selected as a ‘fair’ alternative regarding how students graded. This computer-generated system determined an individual’s grades grade through combining an assortment of different factors including:

- The school’s previous results.

- The average school grades in the area.

- The student’s previous and current predicted grades.

- Teachers’ opinions.

- Mock examination grades.

One major problem was that last year, the algorithm heavily reduced the grades of students in low-income areas, whilst students educated in affluent areas – and those with a grammar or private school education – were generally rewarded higher grades.

Following public outrage, the Government took a U-turn and decided to award students their Centre Assessment Grades (CAG) – teacher predictions. However, because this change was made in the days following A-Level results day, many students with the CAG grades required by their chosen university had lost out on their place. This is one reason the Government have changed their strategy this year.

Firstly, GCSE and A-level results day will be earlier than traditional to provide a ‘buffer’ period in which students can appeal their grades before universities award any places. As opposed previous years, students will not face any financial charges for appealing.

Exam boards will also be introducing both GCSE and A-level ‘mini exams’. Although it is not compulsory for students to sit these exams, schools across the country will provide students the option to complete them so to provide greater evidence of the academic level of students.

How do students feel about teachers allocating grades?

Response is varied. One A-level student told The Guardian that the 2021 assessment method is unfair because “there is a different mindset during the end-of-year exams”, whilst across the year “students tend to not work as well”. Another A-level student told The Guardian that the lack of communication from the Government makes the recent cancellation of exams “too little too late”.

On the other hand, many students view the government’s decision as justified, with one GCSE student saying, “There’s no way exams could go ahead, it wouldn’t be a level playing field.”

The response outside student community is also varied. The Education Policy Institute has raised concerns about grade inflation and the effect this will have on the way universities and employers distinguish between applicants. Alternatively, charity Parentkind has stated that “teacher assessment is the fairest way to test pupils under the current circumstances.”

To quote the National Education Union, the government’s decision for teachers to grade their students is the “least worst option” – especially when considering last year’s controversy.

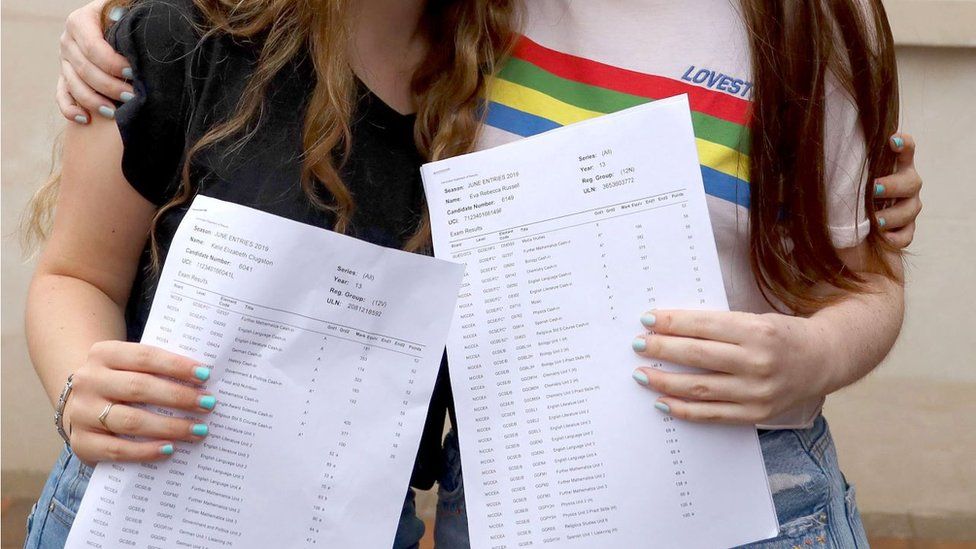

Image Credit: BBC