A UN report on human rights abuses in Iran, released on the 10th February, details “electric shocks and the administration of hormones and strong psychoactive medications” for lesbian, bisexual, gay and transgender children. (Content warning: references to homophobia and transphobia)

The issue was first raised by the UN in 2016 and Javaid Rehman, Special Rapporteur for Iranian human rights, condemned the practices as “torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment”. Rehman stressed that the Iranian state’s permission of such medically unnecessary ‘treatment’ is in violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

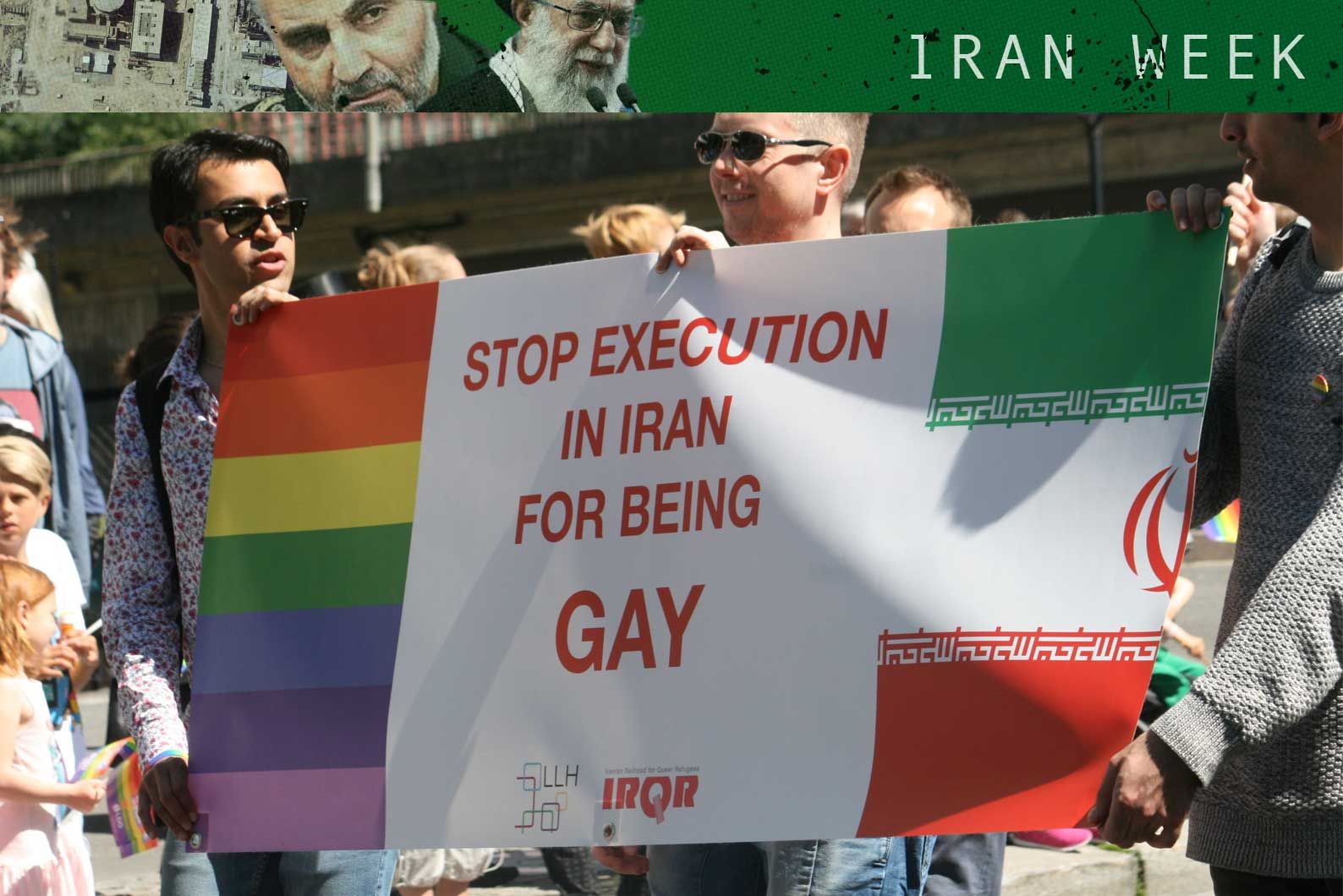

Abuses such as these are common around the globe for LGBTQ+ individuals. Even in the relatively progressive UK, ‘gay conversion therapy’ has not been legislatively banned. It is not, however, medically sanctioned and is widely condemned within our public sphere. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Iran, where homosexuality is currently criminalised – in some cases carrying the death penalty- and transgender existence is only marginally recognised. Cisgender gay and lesbian individuals are often pushed by Iranian doctors to medically transition, in order to achieve a destructive caricature of heterosexuality. These individuals, along with those who are transgender, face widespread social stigma and discrimination. Conversion attempts are no less abusive or traumatic, wherever they take place, but the extreme risk to Iranian youth is no doubt much higher than that faced by those within the UK.

There are many other countries with similar practices: homosexuality is currently illegal in 70 UN-recognised states and punishable by death in 6, including Somalia, Mauritania, Sudan, Saudi Arabia and northern Nigeria. As is usually the case in Iran, non-capital punishments such as lashings or imprisonment are often used instead – but thousands of repeat offenders have been killed in just the last 50 years. In Iran, homosexuality only became criminalised in 1979, following the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini. Before this relatively recent cultural upheaval, same-sex relationships were taboo but generally tolerated under the regime of the Pahlavi dynasty. The right for transgender individuals to have gender-affirming surgery was addressed by Khomeini’s government in the mid-1980s but the state’s account of trans identity is a medicalized “gender identity disorder.” Outright Action International’s report, ‘Being Transgender in Iran’ condemns this as having “reinforced the stigma rooted in the notion that trans individuals suffer from psychological and sexual disorders and require treatment to become ‘normal.’”

In response to this abuse and suffering, what should the LGBTQ+ community and allies in more privileged situations be doing? Many issues that are of concern in Western countries, such as marriage equality – though important in their own right, seem less of a priority when compared to the overt violence that others face due to extreme regressive governmental policies. Is it unfairly interventionalist for I, or anyone without cultural ties to Iran, for example, or Nigeria, Somalia or even famously homophobic Russia, to criticize without an intimate understanding of the religious and cultural basis of these oppressive policies? Having grown up in the Church of England, is it easier for me to criticize Russian homophobia than Iranian, because of its Christian, rather than Islamic justifications?

It is important to look to activists who do have intimate knowledge of the policies and societies in question for guidance and an example of how to help. Arsham Parsi is an Iranian activist living in Canada, who founded the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees and is also a part of the Toronto-based Rainbow Railroad group. These organisations provide material and emotional support to queer individuals, and fight for asylum for those who need to leave their home countries due to homophobic or transphobic persecution. Obviously, support for these sorts of organisations, particularly from those with legal knowledge, is a great way to help the victims of the most severe LGBTQ+ rights violations globally. Simply addressing the issues and putting pressure on governments can be of use too, though. Lesbian activist Saghi Gharaman was forced to become a refugee in Turkey, after fleeing Iran, and now also resides in Canada. She believes that the current regime in her country of birth will bow to international pressure if applied correctly. According to Gharaman, Khomeini’s government doesn’t “care much about Sharia; only staying in power counts for the group that is ruling Iran.” She then asserts that “Islam allows for many different meanings and interpretations of its rules” and reminds us that legislative homophobia only became criminal with the 1979 revolution.

The UK decriminalised homosexuality in 1967, at a time when it would not yet have even become a criminal matter in Iran. Many activists and writers have drawn attention to the homophobic legacy that colonial Europe spread globally, particularly in Africa. Val Kalende asserts in the Guardian that the European Penal Code system imposed on Africa in previous centuries introduced the criminalisation of homosexuality and “the Bible became the credo of African morality, disordering African sexuality to missionary positions of heteronormativity.” It would be too simplistic to blame the West for global homophobia, but I think that any anxiety Western LGBTQ+ individuals have about overstepping our responsibilities should be dismissed.

Though the issues currently focused on within our discourse, such as marriage equality and bathroom rights, are not in any way trivial, the scope of the conversation should be widened as far as possible to comprehensively address LGBTQ+ rights globally. Systemic torture, murder and oppression are not acceptable in any context and should be at the forefront of our minds when it comes to activism. We should follow the lead of activists with experience in the relevant matters and look to learn how and where our help and enthusiasm can be best put to use.

Header image credit: tabletmagazine