If you ever partook in the Duke of Edinburgh Award at school, you should be familiar with the workings of a compass, which uses the Earth’s magnetic field to point us in the right direction. Well, humans are certainly not the first or the only organisms to harness the Earth’s magnetic rays. In recent years, giant magnetic fossils have been found that date back to over 56 million years ago. Whilst the exact organism that produced these unique fossils remains a mystery, scientists have been using them to unlock the secrets of Earth’s past – in particular, its climate history.

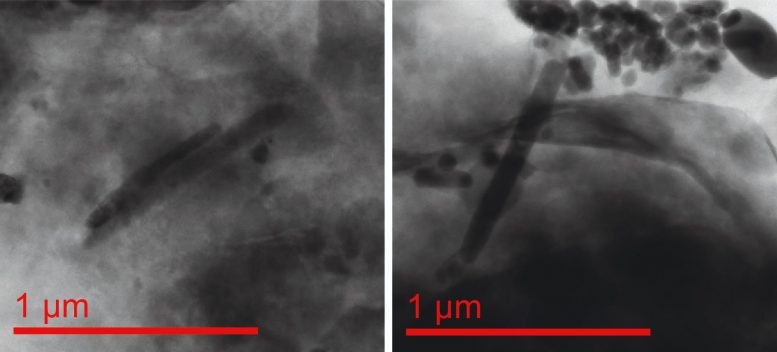

Today, some bacteria have been found to produce small particles of iron oxide – only 1000th of the width of a human hair. When combined en masse, these particles can align along the Earth’s magnetic field and act as a sort of compass to these organisms, helping them find the optimal conditions in their watery environment.

Remarkably, giant versions of these magnetic structures have been found deep beneath the Earth’s surface in recent years, similar to the ones produced by modern bacteria today. These ‘magnetofossils’ date back to over 56 million years ago and were formed at the beginning of a time called the Eocene.

This is of great interest to climate scientists as the rise and fall in abundance of these fossils in the fossil record coincides with that of global temperatures. They reached their greatest size and complexity during Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, where 3-10’000 gigatons of carbon were released into the ocean and atmosphere in less than 20’000 years. As its name suggests, this period saw the last great rise in global temperatures before that of modern times, though this rise was 170 times slower than what we are seeing today.

Scientists can use these fossils to map Earth’s climate history, but the process is costly. Analysis involves a technique called electron microscopy which is incredibly expensive and the whole procedure destroys the unique fossils. As such, their use is limited.

However, a new study published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of America) revealed that researchers have developed a way to study these fossils without destroying them. The researchers used first order reversal curve (FORC) measurements to analyse the fossils, which, in short, involves subjecting them to magnetic fields in order to identify the different types of particles they contain. This helps scientists recognise the occurrence of these fossils without actually seeing them.

Like all great discoveries, the study of these fossils only raises more questions. The iron oxide particles produced by modern day bacteria in no way match the size and complexity of these fossils and no other organisms alive today produce anything like it. So, what created these unique structures, and what happened to them?

The answer may lie in the fossil record itself. During known cooler periods, ‘magnetofossils’ were seen to disappear and the end of the Eocene is marked by the formation of the first permanent Antarctic icesheets. Is it possible that cooler conditions made the Earth uninhabitable for these mysterious organisms, as the water no longer provided the conditions and nutrients they needed to survive? It is questions like this that provide new and interesting avenues for researchers to explore in the future.

By Catherine Upex

Header image: Pixabay