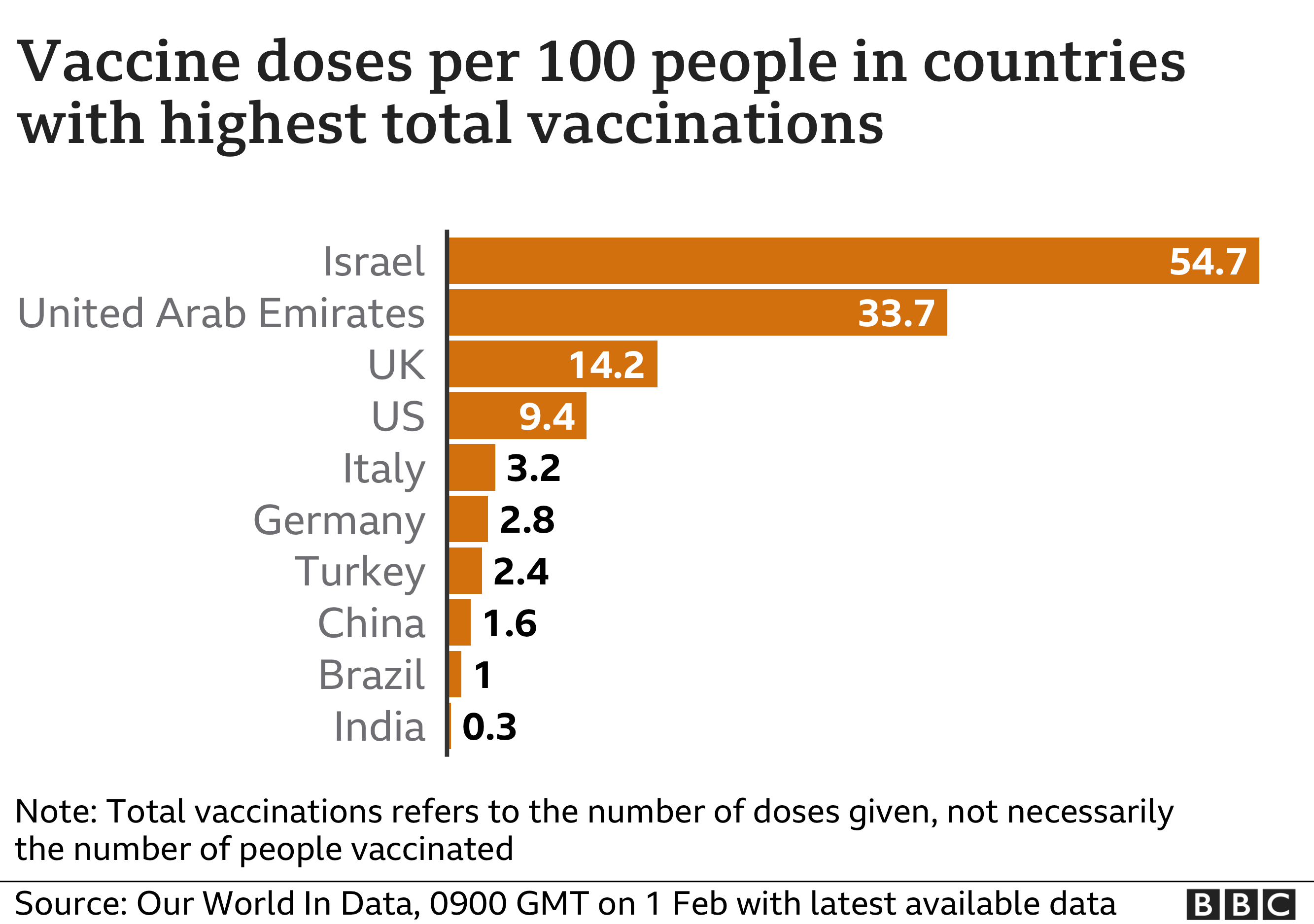

Almost a year on since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the UK, people are finally getting vaccinated. As of 3rd February, a total of 10 million people in the UK had received their first dose, putting the country in an amazing position in terms of vaccinations by population. With the vaccines being prioritised for the most elderly or frontline health workers, most students are yet to receive the vaccine, however it is likely that students will get their first dose in the coming months.

Working out what’s what with all the vaccine information can be extremely confusing – with most people getting their vaccine not really knowing much about it. So here is a compilation of the most useful information to know:

What are the different types of vaccine available and what is the difference between them?

From 330 vaccine candidates there are only a few making it into people’s arms. In the UK at the moment, most people are being offered either the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (approved early December) or the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (approved late December). Another vaccine called Moderna was also approved in January, and the UK has placed an order of 17 million doses that are expected to arrive in the Spring.

Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccine

This vaccine was developed jointly by the companies Pfizer and BioNTech. BioNTech is a German company that developed the vaccine under the program ‘Lightspeed’ in January 2020. Pfizer is one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world and, among other investors, funded the project with about $2 billion.

It is an RNA (Ribonucleic acid) vaccine; meaning it is made with the genetic code specific to the coronavirus antigen – located on the spike protein on the surface of the virus. When injected into a person, the RNA tells some of the body’s own cells to make the same antigens as the coronavirus. The immune system then kicks into action to make antibodies that help destroy these cells; these antibodies stay in the body and are ready to destroy the real coronavirus if the person ever gets infected.

One of the problems with this vaccine is that it has to be stored at -70˚C and, once out of the freezer, it must be stored in a refrigerator (at 2-8⁰C) and used within 5 days. Most GP practices or vaccine centres do not have this kind of storage equipment; adding complexity to an already difficult logistical operation. This cold temperature is needed as the RNA components are fragile and break down in warmer environments, making the vaccine ineffective.

The Moderna vaccine is also an RNA vaccine and works in a similar way.

Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine

A team of scientists in Oxford designed the vaccine in early January 2020. This uses the more traditional vaccine mechanism of a vector and is different from the newer RNA vaccines. This means that a different virus, in this case a chimpanzee adenovirus (the vector), is modified so that it can’t replicate and is also given the antigen protein from the coronavirus. When injected, the immune system produces antibodies to combat the attached COVID-19 antigens. As the inert vector virus cannot replicate, it is not a danger to the person. The antibodies made for this virus again will remain in the body ready to combat the COVID-19 virus.

This group in Oxford also needed a large company to finance the vaccination programme, who could take on the risk of the vaccine not working and therefore survive a large financial loss. AstraZeneca were chosen due to their multinational network and agreement not to make a profit from the vaccine during the pandemic. The British Government also provided nearly £90 million in support.

The results of two further vaccine trials were announced on Friday (29th January): one vaccine from the company Johnson and Johnson showed 66% effectiveness against COVID-19, and a vaccine from Novavax yielded substantial protection against the new South African variant.

Why do we need two doses?

The UK Government has received a lot of stick for lack of clarity on whether people should receive one or two doses of the vaccine and, if two, how many days apart?

But why would we need two doses? Gary McLean, a molecular immunology professor from the London Metropolitan University, explained:

“The first shot primes the immune response and the second shot mobilises the cells again to respond even stronger – the result being a much better and hopefully prolonged immune response that retains memory. Without the second dose I would suggest that the immunity gained will not be strong enough and will not last long enough – particularly for the genetic vaccines such as Pfizer.”

When looking at the efficacy results for the vaccines there is a lot of obscurity and confusing statistics, but results are clearly showing an improved efficacy from two doses compared to one. However, one single dose is still somewhat effective; 64% in the case of AstraZeneca compared to 90% after two doses. This led to some people, including former Prime Minister Tony Blair, suggesting we give a single dose to a larger number of people; this would potentially mean a closer end to lockdown restrictions but would be against scientific recommendations. At the moment the Government has gone for a compromise approach of pushing the second dose up to 12 weeks after the first dose – contradictory to World Health Organisation advice that this should only be in exceptional circumstances.

What next for the vaccine?

There are a lot of questions and a lot to come regarding news of the vaccine. Of course the main question is: will it work?

No vaccine offers 100% protection but their arrival certainly lifted hopes that the spread of COVID-19 could be slowed or even stopped completely. By vaccinating the most vulnerable people first, the Government aims to drastically cut the number of deaths and people in hospital, making room for routine elective surgeries to take place and keep the NHS from being overwhelmed.

Also, it is unclear how long the immunity will last; will we need to get the vaccine every year like we do the flu vaccine? The answer to this question is not known but could well happen. Matt Hancock, the Health Secretary, said:

“I think it’s highly likely that there will be a dual-vaccination programme for the foreseeable, this is the medium-term, of flu and COVID.”

In terms of whether the vaccine will end the pandemic.. the jury’s very much out on that one. But, with the UK now in its third lockdown and some regions experiencing the highest number of COVID patients in hospital since the start of the pandemic, many are placing big hopes on the success of the vaccine programme.

By Lara Shoesmith

Header image: torstensimon/Pixabay