As 2021 is expected to bring heaps more Nordic content to Netflix, I thought I’d have a look through the Nordic cinematic archives and share some of my favourites—foreign films in a student newspaper, whatever next! As all my favourite Nordic films turned out to be Swedish, I decided to spotlight Swedish cinema and hopefully highlight its underrated contribution to European film.

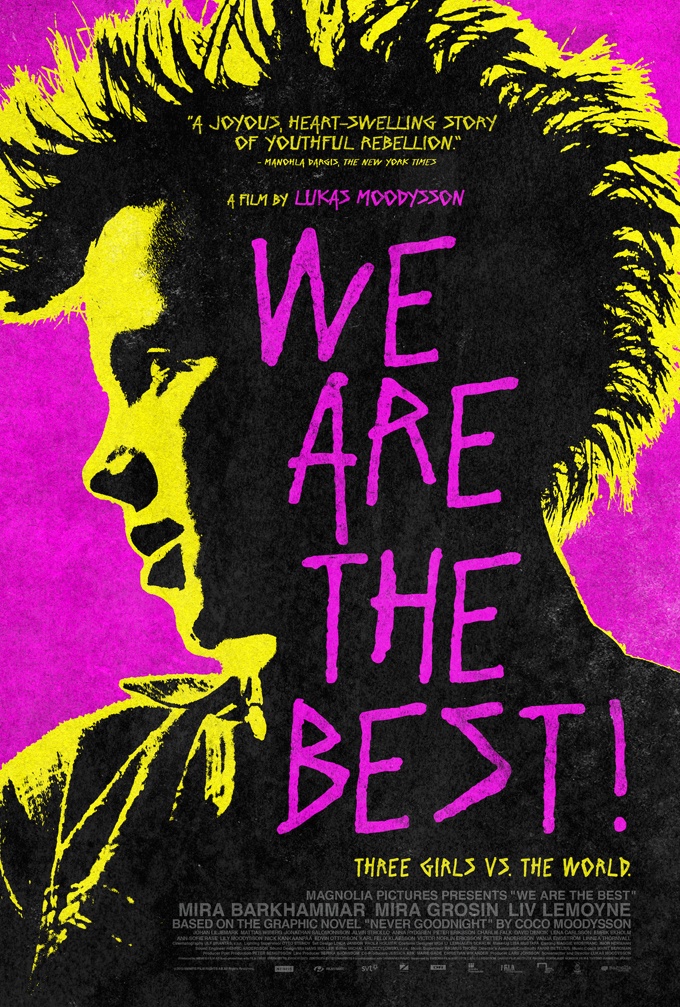

We Are the Best! (Vi är Bäst), 2013, dir. Lukas Moodysson

Stockholm, 1982. Two outcast thirteen-year-old girls, Bobo and Klara, express their anti-capitalism, anti-fascist, and anti-disco views through a love of punk rock. Unable to actually play any instruments, they reel in the support of an equally outcast, church-going, classical guitar playing classmate, Hedvig. I naively expected the film to follow the rough course of a Muppet movie with that Kermit quote, “a bunch of weirdos make a family.” Instead, it was one of the bleakest, rawest portrayals of being thirteen.

Whilst other reviewers have pointed to the film’s lightness and warmth, I was struck by Bobo’s struggles with inferiority, jealousy and envy. Moreover, they all wrestle with the decision to either distance themselves from or to embrace the cliquiness of subculture-culture, its gatekeeping and pigeon-holing used to filter out the “mall punks” and “proggers”.

Bobo and Klara’s sardonic mocking of mainstream ‘80s pop culture was a refreshing break from nostalgia fests like Stranger Things and GLOW. Through a surprisingly nuanced portrayal of the ‘80s, I learnt a lot about Stockholm’s punk scene and highly recommend checking out KSMB and Ebba Grön.

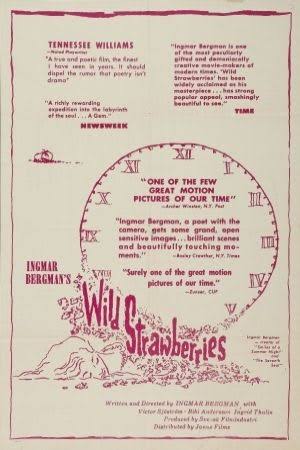

Wild Strawberries (Smultronsträtten), 1957, dir. Ingmar Bergman

A classic of Swedish cinema by Sweden’s most famous film director, Wild Strawberries follows the journey of a 78-year-old prolific but self-absorbed doctor, Isak Borg, to collect an honorary degree accompanied by his Strong Female Lead and voice-of-reason daughter-in-law, as well as an eccentric cast of characters picked up on the way. It’s a film of contrasts; the dialogue-heavy realism, in which the characters each reflect on Life’s Big Questions is interrupted by both Isak’s dreamy flashbacks to woozy, languid summers as a teenager and his present-day nightmares, with their surrealist elements of horror and film noir.

Philosophically, it pinpoints the post-war but pre-60s transition between modernism and postmodernism. The characters discuss themes of gender and sexism (prepare for a lot of sexism), family, Christianity, death, and love, including an uncomfortable amount of cousin-related incest. Isak and his flashbacks to coming of age in the late 19th century represent the “old world”, whilst the characters from the next generation and their cynicism, or perhaps realism, centring on themes like atheism and antinatalism reflect the new. It’s a rather pessimistic take on life, the options seem to be prejudice or despair; a young, exuberant, and rather familiar-looking hitchhiker balances out the tone of the film with sweetness and hopefulness.

Force Majeure, (Turist), 2014, dir. Ruben Östlund

Östlund’s less famous predecessor to The Square presents an equally visceral and human dark comedy about modern marriage, written in a bid to increase divorce rates. At an Alpine ski resort, a super middle-class, super nuclear family face a marital crisis after the dad runs away from his wife and children in an avalanche, causing the mum to reassess his values and loyalties to the family, all against the unrelenting pressure to enjoy their holiday and spend “quality” time together.

Force Majeure is not so much a character study but a fully-fledged study of relationships. We meet another two couples, whose age gaps and polyamory contrast the idealised, nuclear family. We spend little time with the individuals in the couples; we know them largely from how they interact with their partner. Brilliantly acted, it’s all about the moments in-between, the silences and knowing looks as much as the dialogue. Like relationships, it’s awkward, cringey, and sometimes close to heart-breaking.

Östlund wants the impossible conversation of how we’d act in a life or death situation to transcend the fourth wall. He wants this film to be a litmus test for the longevity of a relationship; he wants to force couples watching to have difficult conversations, hoping to challenge our how we understand each other, and how we understand ourselves.