Ana Hill López-Menchero investigates the extent of the persecution of Uighurs in China. She heard from Aydin Anwar, who has had 93 relatives go missing.

The Uighurs are a largely Muslim, Turkic ethnic minority group native to the Xinjiang province of north-western China, traditionally East Turkistan. It has long been suspected, and more recently, reported, that the Chinese government has been gradually forcing Uighurs into what they call “re-education camps”, but what have been rebranded in the West as ‘Chinese concentration camps.’

There are other rumours of forced sterilisation of Uighur women and high levels of surveillance. It has been alleged that Huawei played a part in this surveillance. These allegations came about after documents were revealed on Huawei’s European website mentioning a “Uighur alarm” system they had developed with Megvii.

However, when asked about this alarm system Huawei told the BBC that they “do not develop or sell systems that identify people by their ethnicity, and we do not condone the use of our technologies to discriminate against or oppress members of any community.”

In 2019 the US put Megvii on a trade blacklist in 2019, and 13 UK MPs and members of the House of Lords published a letter over fears that Huawei was “facilitating a programme of ethnic repression”. Footballer Antoine Griezmann ended all association with the ‘Chinese tech giant’ after the scandal became more widely reported.

There are also deplorable rumours of China harvesting organs from Uighurs. ‘The China Tribunal’ is an “independent, international people’s tribunal” looking into these allegations, which China strongly denies of course. In an article in The Guardian it is revealed that analysts have called the situation a ‘cultural genocide.’

“93 of her relatives have gone missing due to Chinese oppression. She told me that ‘one of the most terrifying things is the fear of the unknown’”

The Chinese government has remained adamant that these camps are for education purposes. This is further claimed in ‘glossy reports’ and photos distributed by the government, as explored in a 2018 BBC investigation. Initial evidence of these camps was seen from satellite images of desert land outside of the town of Dabancheng. In mid-2015 the images showed empty desert land, but almost three years later the land was no longer vacant, and the images revealed a ‘highly secure compound’ with 2km of exterior wall and 16 guard towers.

This is not the only piece of evidence of camps. In 2019 official documents were leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). In the documents was a nine-page memo from 2017, sent to the officials in charge of running the camps from Zhu Hailun. At the time Zhu Hailun was the deputy-secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official. In the memo, there were various orders, such as “never allow escapes” and “[ensure] full video surveillance coverage of dormitories and classrooms free of blind spots”. From the leaked documents, it can be understood that these camps are not simply educational facilities.

Moreover, recently Dr Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, Washington, uncovered documents with evidence that half a million minority workers were being forced to pick cotton. Zenz says himself that “for the first time we not only have evidence of Uighur forced labour in manufacturing, in garment making, it’s directly about the picking of cotton, and I think that is such a game-changer.”

The relationship between the Uighurs and their modern-day political masters has long been as fraught as it is distant.

The uncovered documents included online government policy papers and state news reports from 2018. These documents had information that the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps had sent 210,000 workers to pick cotton; what is suspected is that it was not their choice to go. The Xinjiang region produces 84% of China’s cotton and 20% of the worlds, creating dire decisions made by countries receiving cotton from Xinjiang.

Chinese officials deny any claims that Uighurs and other minority groups are being sent to ‘Chinese concentration camps’ or forced to pick cotton. The foreign minister defends the cotton picking, saying that the “workers from all ethnic groups in Xinjiang choose their jobs according to their own free will and sign voluntary employment contracts in accordance with the law.”

Xi Jinping, the President of the People’s Republic of China, set up a national anti-poverty campaign to eliminate absolute poverty. This has now been used as an explanation for the “re-education camps”.

There is also a deeper conflict between the Communist Party and the Uighurs. Another BBC report claims that there was ‘a history of rebellion and resistance to Chinese rule. The relationship between the Uighurs and their modern-day political masters has long been as fraught as it is distant.’

The Xinjiang province had great investment opportunities as a result of the great mineral wealth in the region. However, the Uighurs have resented the fact that they have not been able to profit from their region for a long time. The 2013 car attack on pedestrians and the 2014 train station knife attack triggered stricter security measures in Xinjiang against the Uighur Muslims.

These measures also included legal penalties ‘to curtail Islamic identity and practice.’ These included ‘banning…long beards and headscarves, the religious instruction of children, and even Islamic-sounding names.’ Suddenly all Uighur Muslims were seen as potential threats to the Communist Party.

“Mainstream religious activity, the mildest dissent and any link with Uighurs living in foreign countries’ resulted in detainment.

Leeds Human Rights Journal hosted a seminar led by activist Aydin Anwar, whose family comes from Chinese occupied East Turkistan, 93 of her relatives have gone missing due to Chinese oppression. She told me that ‘one of the most terrifying things is the fear of the unknown’, there is very little information about what has happened to her relatives. She also made clear that this oppression is not a recent development. Unfortunately, this is not an unusual story for people with Uighur relatives. Anwar’s activism began in college after interviewing Uighur refugees in Turkey, but she was also inspired by her father’s activism long before this.

Initially, some Uighurs were released after spending a few months in the camps, but even then, only some would agree to interviews. In these interviews with the BBC, the Uighur interviewees revealed that ‘mainstream religious activity, the mildest dissent and any link with Uighurs living in foreign countries’ resulted in detainment. More recently there have been fewer stories of released Uighurs.

Like Aydin Anwar, many Uighurs live outside of Xinjiang where there is virtually no information about what is happening in recent years. The BBC article speaks of ‘people being deleted from family chat groups or told never to call again’, as even the slightest connection abroad could end in their detainment. Online there is an alarming number of appeals to find relatives who have disappeared.

Action is increasingly difficult unless something can be done to threaten Chinese power and control, as this has been China’s main concern for a long time, simply shown by the persecution of Uighurs.

The UN Committee dealing with human rights issues condemned China’s treatment of Uighurs on behalf of 39 countries. Even so, Aydin Anwar says that the UN has been ‘complicit’ in the ‘genocide’, as the UN human rights council has China as one of their permanent members. Anwar describes this as the equivalent of ‘hiring a paedophile to babysit your kids’.

Many Muslim states have remained silent on the subject, even blocking the motion at the UN in July 2019 to allow “independent international observers” into Xinjiang. It is thought that China’s “Belt and Road” infrastructure programme has benefitted many of these states and they have therefore ‘been bought off’.

This silence from many countries is down to ‘blood money’ according to Anwar. China has frequently used its economic power to silence countries. Anwar describes the recent block from the US of cotton and tomato products made from forced labour as a ‘huge move’ as ‘it is not until we target China’s economy that…China will start caring about what they’re doing’.

Chinese authorities have now targeted Uighurs for a number of years, but because of Chinese control, the extent of the situation is largely unknown. Action is increasingly difficult unless something can be done to threaten Chinese power and control, as this has been China’s main concern for a long time, simply shown by the persecution of Uighurs.

It is vital to threaten their power and force recognition from state officials of a situation which has grown out of control.

Take further action:

- Raise awareness and keep educating yourself and others.

- Research – https://www.saveuighur.org

- Pressure your local representatives and government to take further action and acknowledge the imprisonment of Uighurs.

- Use your voice to create student organizations, talk to your tutors, and talk to other students.

- Boycott Chinese products.

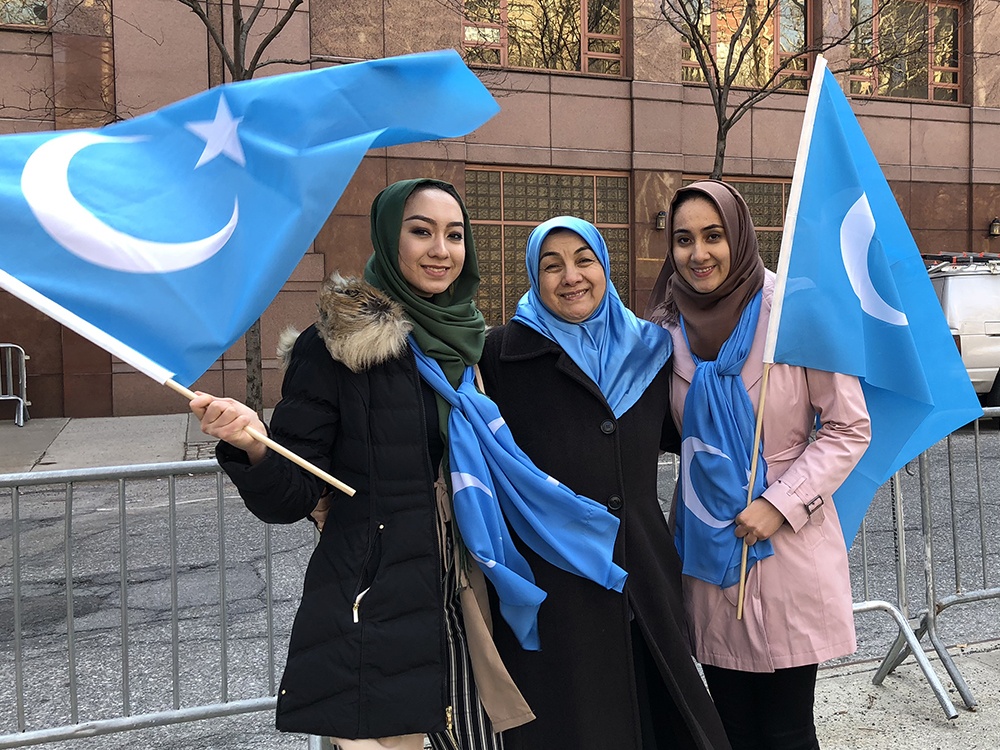

Featured image via Politico