Up until 1958, British publishers could be sent to jail for producing books deemed to have “a tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influence”. Whilst this is no longer the case, it is all too easy for us to forget that such freedom of expression is a relatively new concept, and to take our privilege for granted.

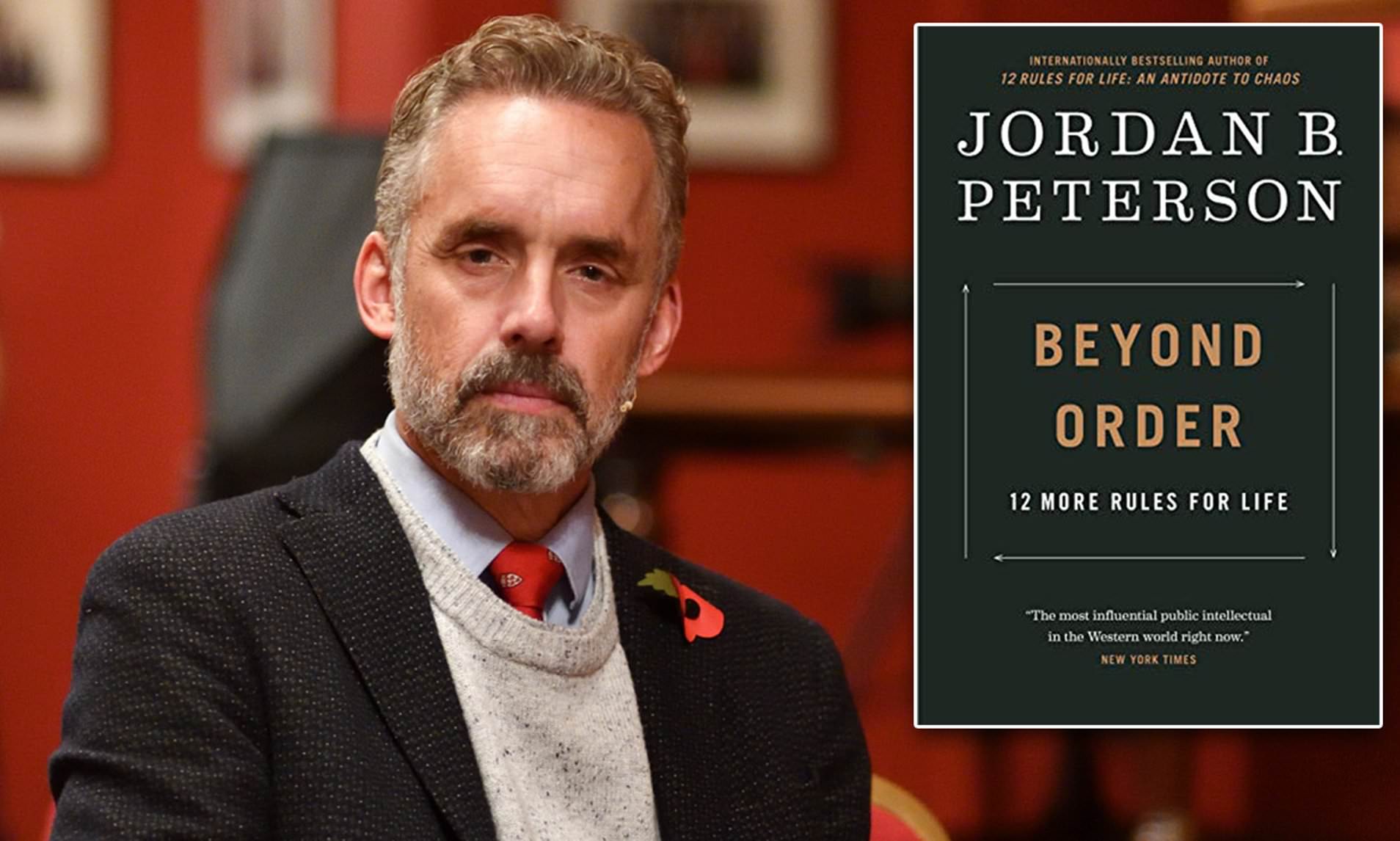

At the end of November, Penguin Random House announced that they would be publishing a follow-up to the bestselling psychologist Jordan Peterson’s hugely successful 2018 book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Whilst externally, the response was largely positive, several employees of Penguin were reported as having serious issues with the publisher’s decision. Bearing in mind the ease at which it is possible to overlook our society’s relatively progressive approach to publishing freedoms, some of this internal reaction was perhaps unsurprising, albeit disappointing.

The employees in question were said to have confronted the management, declaring that Peterson is an “icon for hate speech and transphobia” and “of white supremacy”, some in tears whilst doing so. One complainant stated that “I’m not proud to work for a company that publishes him”, whilst another argued that by taking this decision, Penguin had effectively cancelled out any previous “allyship” they had shown following the death of George Floyd, rendering their words and actions simply “performative”.

It is true that there are people who disagree with Peterson, who throughout his career has tried to tackle some of the most pressing political and social questions that affect our society. Nevertheless, it is also true that there are more people for whom he represents a positive influence on today’s cultural landscape. This is evidenced in the more than 3 million copies sold of his book on his 12 Rules to Life, and of the countless others who turn up to hear him speak at functions – one notable example is a debate held between Peterson and Sam Harris at the O2 area in London. It is also very possible that many of those who oppose Penguin’s decision are not actually as familiar with Peterson’s work as they suggest.

However, whether you agree with Jordan Peterson’s politics or not, there is one thing we should all agree on: if Penguin were to back down now, it would set a dangerous precedent. Whatever your politics, Peterson’s stance on the gender pay gap debate is ultimately irrelevant, as is what he thinks about the Black Lives Matter movement. You can vehemently disagree with him on every issue available, whilst still recognising that the tenets of freedom of expression within the publishing industry have to be preserved.

The focus should always be on the quality of the book, and how economically viable it is as an investment for the publisher. Books such as Peterson’s next work, Beyond Order: 12 Rules for Life, are an editor’s dream, particularly if they are feeling the pressure of a COVID-induced economic crisis. When a book sells as many copies as this one inevitably will, it allows the publisher to fund the salaries of numerous people by approving riskier, potentially less financially successful publications, which otherwise would not be afforded the platform.

It is also worth considering the position of the employees as opposed to Penguin’s decision. One could argue that under the current circumstances, they are very lucky to have jobs at all. The idea that they deserve an expectation of pride in their employer, let alone a say in editorial decisions which could affect the company’s future, is certainly a stretch. Equally, it is important to note that any actions following the death of George Floyd by a corporation such as Penguin will inevitably be performative. By arguing the decision to publish Peterson detracts from any previous ‘activism’ is naive and demonstrates a lack of understanding about identity politics and the marketing ploys used by businesses.

This is not about supporting Jordan Peterson. This is a case of supporting the publishing industry, and the rights of publishers to determine their own agenda. Voicing an opinion on managerial decisions is one thing. Attempting to bully and blackmail their superiors into submission is another. There are plenty of people desperate for an opportunity to get into publishing – if the workers at Penguin cannot respect their employer’s decision, they should stand aside to make way for more open-minded individuals.

The recent news from Hachette that they will no longer be publishing Julie Burchill, after she challenged the integrity of Islam’s Prophet Mohammad, serves as another reminder of the importance of these tenets. We must encourage diversity of opinion in publishing, not try to create a world where we all think the same; that way madness lies.