As morning dawned over Paris on 25 September, the people of the French capital woke up to a brutal reminder that despite the pandemic, the threat of terrorism had never truly disappeared. A stabbing attack in front of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo’s former headquarters was followed by the brutal beheading of a schoolteacher three weeks later, and; most recently, by another knife attack in Nice that brought the total death toll to four.

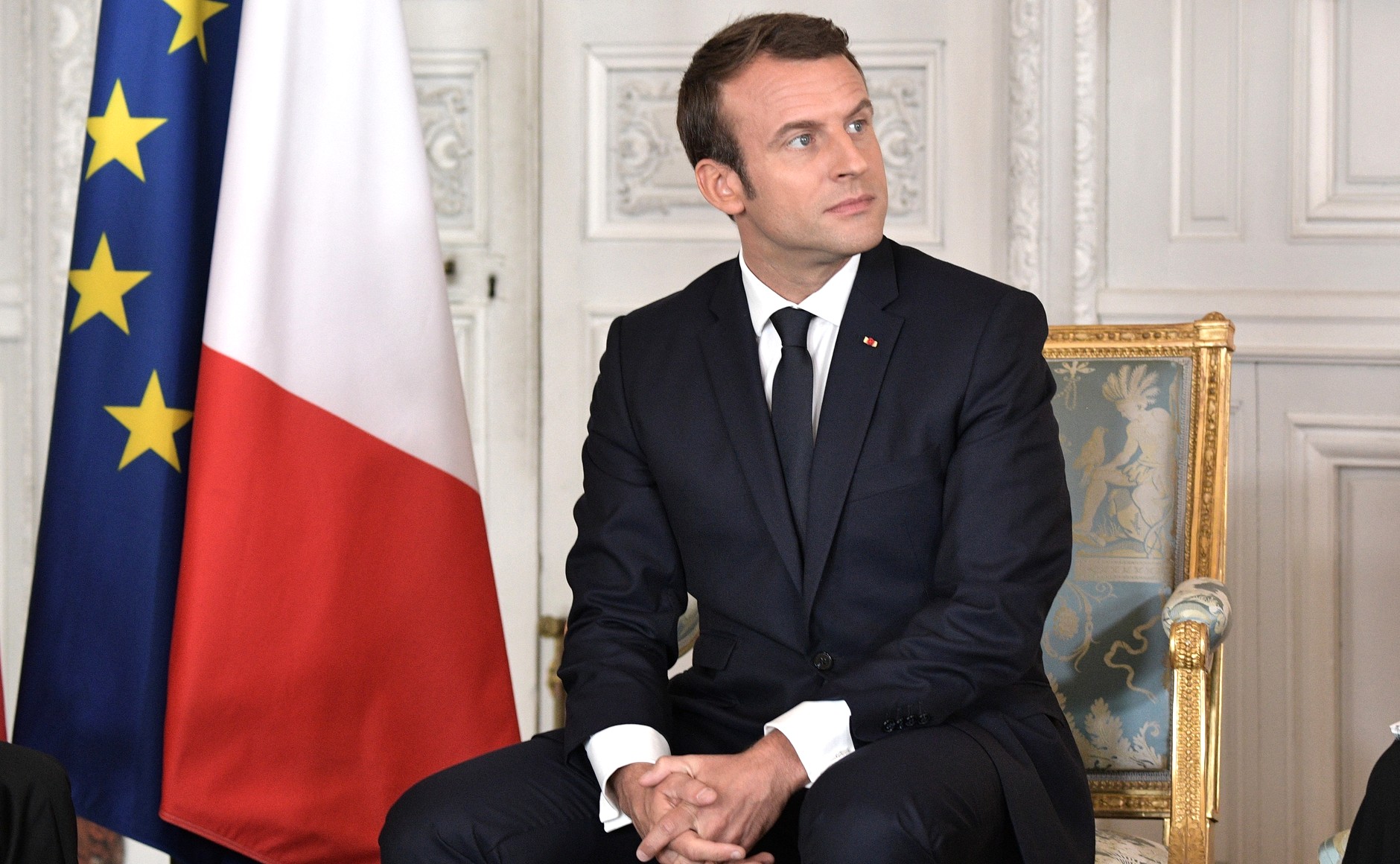

These are hardly the first terrorist attacks in President Macron’s term. The President’s response, however, marks a substantial shift in his rhetoric. His staunch defence of caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed, together with the naming of “Islamist separatism” as the enemy to combat, have triggered worldwide condemnation from Muslim-majority countries. Yet the worst consequences may not be diplomatic.

The French state apparatus has reacted to the recent attacks with remarkable strength: major cities have projected caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed onto their town halls; a grand state funeral was even held for Samuel Paty, victim of the second attack, who was also awarded the highest military honours in France. Macron’s speech during said funeral, while ruthless, was carefully worded to avoid alienating the country’s sizable Muslim community. This tactfulness hasn’t seemed to matter diplomatically: dozens of Muslim-majority countries, led by Turkish President Erdogan, have already called for a boycott of French products. This is no doubt a reference to when the French Interior Minister; Gérald Darmanin, thoughtlessly mused about wanting to see foreign food out of French supermarkets.

It goes without saying that Erdogan’s involvement in this whole affair is purely cynical. He himself is a dictator that crushes both religious and ethnic minorities within his country, but it may not matter. Whilst the diplomatic and economic repercussions of the boycotts remain to be seen, the incident is bound to further inflame the already embittered Muslim community in France. The Interior Minister’s comments do little to help. The far-right Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National) party has already called for a ban on all immigration and spoke of “Islamic acts of war”.

Indeed, it is precisely Marine Le Pen’s looming shadow that likely pushed Macron to take the forceful stance he took. While the president may have staved off Le Pen in 2017, the allure of populism has hardly died out. This year’s local elections across France saw Le Pen’s party eke out a mediocre showing—but so did Macron’s. In The President’s head, the Rassemblement National is almost certainly a beast lurking in the shadows and ready to jump out at a moment’s notice.

It’s little surprise, then, that he spoke the words “Islamist separatism” with such emphasis, similar to how Donald Trump spoke of “radical Islamic terrorism” as if it were some politically incorrect thoughtcrime. In another surprising twist, Macron; a staunch European integrationist, has even proposed to reform the Schengen Treaty to allow for more border controls.

It is hard to determine how sincerely he meant that, or just how much his words are a political calculation to subdue Le Pen’s potential electorate. What’s harder still is to predict what will happen now. In the short term, France may become the prime target for Islamic extremists lashing out against Charlie Hebdo and the state that’s defending it. The resulting police crackdown and rhetoric will only alienate France’s embittered Muslim population further, a vicious cycle with few obvious solutions. Musing about banning foreign food from French supermarkets is not of them.

Whichever the case, one thing is clear: our society must leave no room for intolerance. Speech, even that which we despise, must be met with speech—not with a cleaver.

Thomas Whithorn

Image source: Wikimedia Commons