Have you ever wondered why the little things get to you so much? Or what’s making you so impulsive and hot-headed? Well the answer is simple, it’s the delayed maturation of your prefrontal cortex.

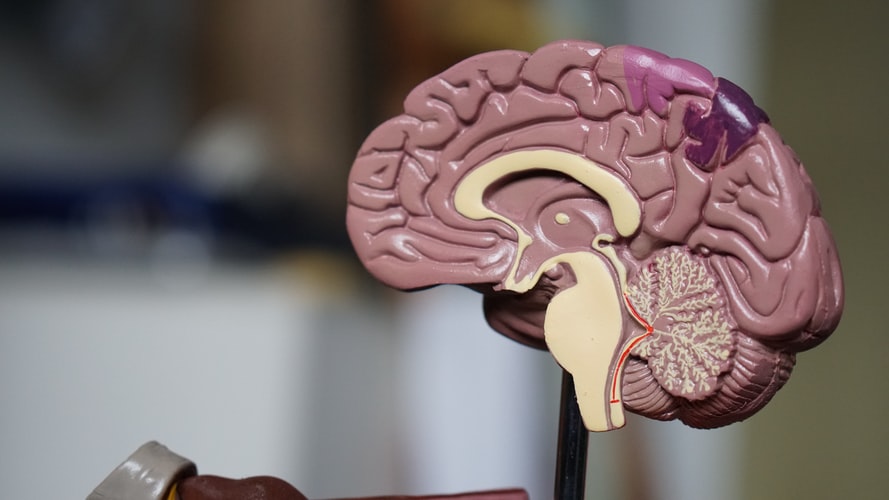

First, it is important to note what your prefrontal cortex (PFC) is responsible for; in a nutshell, your PFC is the rationalising voice in your head. It sits at the front of your brain and deals with conflict between emotion and reason. The PFC focuses your attention on a task, controls your impulses, simulates behavioural consequences and is essential for categorical thinking.

Whilst the other regions of your brain are fully matured and are working at full force, it is your immature frontal cortex that is causing all the problems. The science is simple, in your adolescent years, your frontal cortex has fewer neurones, and therefore synapses, than the adult brain. There is also a large amount of grey matter (unmyelinated neurones) which are less efficient signallers – in fact, your frontal cortex does not fully mature until sometime in your mid-twenties.

So, what does this mean for us? Well, the immature PFC means that it is less successful in rationalising the other regions of our brain that stimulate intense emotion. A brain with a mature frontal cortex will communicate with these other areas to provide emotional context, which neutralises feelings of anger or upset. Unfortunately for those of us with adolescent brains, the emotional response continues to grow in the absence of this rationalising force. Robert Sapolsky – a professor at Stanford University – gives an excellent example of this: imagine you receive a bad grade on an exam, the teenage brain immediately jumps to the conclusion that you must be stupid. The rational PFC, however, focuses on the context: perhaps you were ill that week or didn’t revise as much as you should have.

The good news is that we get better at this reappraisal throughout adolescence. The bad news is that the teenage inability to rationalise is particularly prevalent regarding social exclusion. For both teenagers and adults, when an incident of social exclusion occurs the regions of your brain that stimulate anger, disgust, and pain perception light up. The key difference is that in adults, the ventrolateral PFC kicks in almost immediately and asks the question “why am I getting so upset?”. For teenagers, there is barely any response from the PFC so young people are left with a heightened emotional response and feeling of rejection. This notion that the adolescent brain feels a stronger sense of rejection correlates strongly with the urge to fit in and hence explains why peer pressure is so prevalent in teens.

By Ella Spittall

Header image: Robina Weermeijer/Unsplash