Art has always provoked us to challenge ourselves and the world we live in. It could be argued that art’s main task is to perplex, probe and disturb. However, unlike other means of commentary, art often remains just commentary. Art can require time to be created, to ponder and respond to change. It may not often have the immediacy, or spontaneity, that many social causes often have. Sometimes, the questions that an art piece may explore are posed to a select group of people, behind pricey exhibition tickets. However, art can fight for change in its own right, with people on the ground, ‘out there’ in the world, where it can be socially engaged. The results of taking art outside of a gallery setting, or challenging the nature of systems within these settings, can create real and lasting change.

Direct Action

When the words art and activism are put in the same sentence, many will probably recall the Guerrilla Girls, who are an art group that use humour to publicly expose sexism and racism within places of culture and wider society. Their unveiling of discrimination, via billboards, posters and interventions, has showcased the corruption associated with many institutions. Using creative expression in this way is powerful, because to demand reform, change or abolition, it requires the type of art to be disruptive – often of the institutions that artists and creatives seem so bound to.

Art can, therefore, be a political act within a museum setting, although when it is generally legal or works in cooperation with the said institution, change might be small or non-existent. Manchester Art Gallery caught people’s attention while doing this, as they facilitated a performance to protest and remove John William Waterhouse’s painting Hylas and the Nymphs, due to its depiction of nude young girls.

Challenging Representation

Galleries and museums should reflect culture. However, these spaces are seemingly not representative of all groups of people. In these institutions, exhibited objects are often stolen from cultures as an outcome of the violence and exploitation of imperialism. As well as looted items, there are still portraits on display (as well as statues of them in our town centres) of figures who have caused pain and suffering or facilitated systems of injustice, the consequences of which still affect people’s lives today. Galleries still hang paintings of people, whose depictions are insensitive or problematic, for example the Portrait of Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, as Diana in Tate Britain, which depicts a white woman surrounded by black children and dogs on leashes. Furthermore, artists who come from varied backgrounds sometimes do not have the ability to enter these spaces or are discriminated against doing so. Therefore, work exploring race, gender, sexuality, disability and class might be lacking, with these places seemingly reserved for a certain type of artist and audience. When work from artists made up of people more representative of the population gets a chance to be displayed, with predominately white male critics, it is not able to be critiqued in an appropriate way.

We must remember that art is part of the conversation of representation and decolonising and queering collections must become a priority for institutions. These spaces cannot be reserved for a certain type of person if the society they sit in harbours a diversity of people. Some artists make work that is directly about this, tackling these gazes with an anti-institution stance. Turner Prize-winning Lubaina Himid often plays with contexts, contrasting her large paintings against the backdrop of grandeur in a gallery’s collection. The most recent installation in the Tate’s Turbine Hall Fons Americanus, by Kara Walker, also challenges how art is often tied to institutions, or their colonial histories, within the institution of the Tate itself. However, galleries exhibiting work that challenges colonial legacies is somewhat ironic when these institutions don’t challenge this first, within themselves.

Documentation

The very nature of some art can be political, such as graffiti, which by its creation is an illegal act of defiance. However, rebellious art is not necessarily limited to the streets, with artists like Ai Weiwei known for his provocative artworks that become a form of protest. He often uses documentary to record stories and spread information, or gather people together to investigate and critique the actions of the Chinese government, as well as the wider world we live in.

Gillian Wearing is another example of someone who uses film, as well as photography, to highlight imbalances of power and deprivation in society. Her work Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say involved stopping members of the public in the street and asking them to be photographed with what was on their mind. Not only does this explore public personae, truth and inequality. It also puts power into the subject of the documentation, allowing them to control their representation in the art piece. This, of course, raises discussions around art as a documentary device, which when used sensitively and appropriately helps to draw attention to what mainstream journalism may choose to ignore or not deem to be important.

Public Information

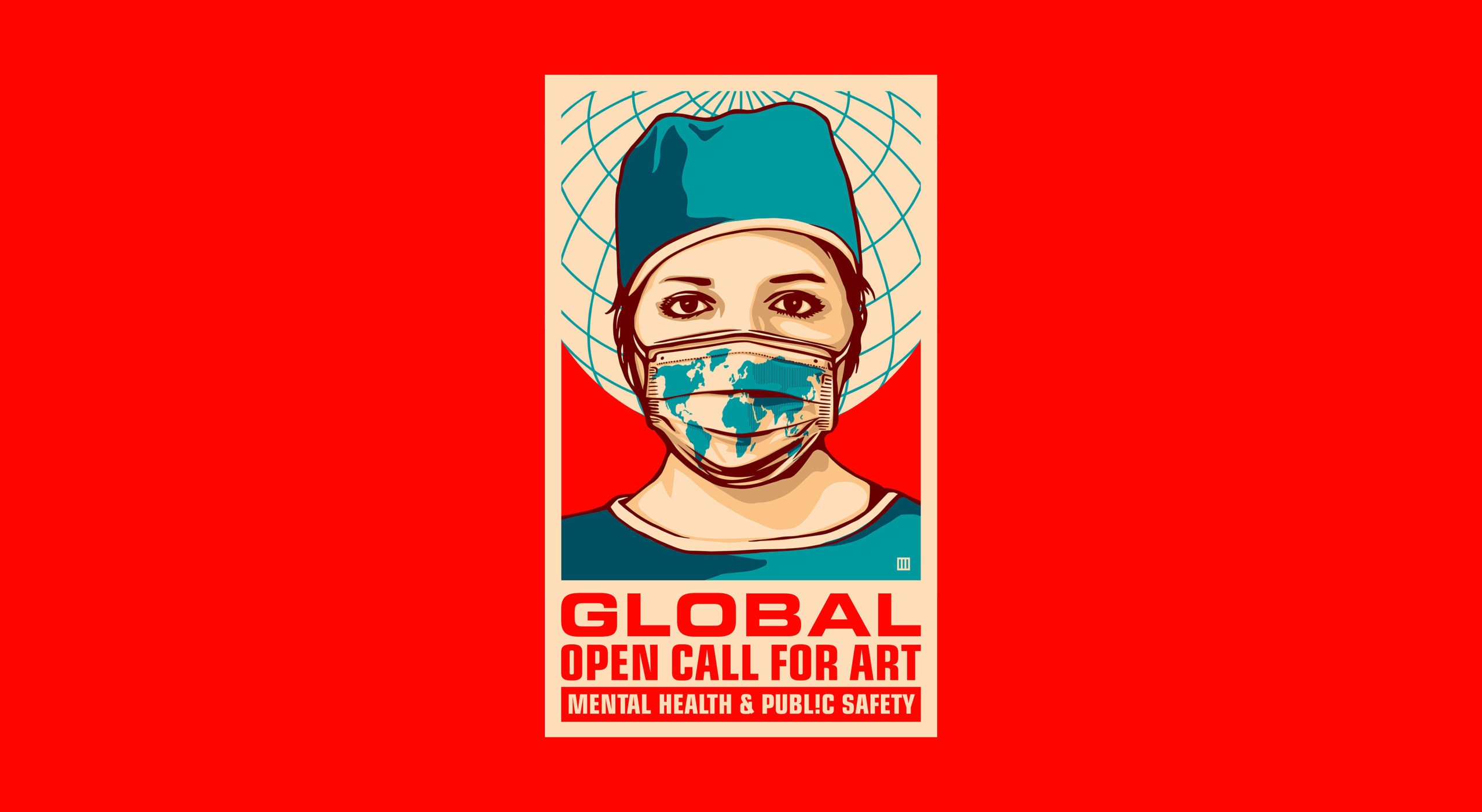

Image-making has a role in informing and educating. This art may include posters, or banners to be used at demonstrations in order to spread public awareness. Some examples include Sister Corita Kent, who dedicated her life to fighting for causes, Bob and Roberta Smith, whose infamous Make Art Not War hangs in every art school and Keith Harring, whose work raised awareness of the AIDs epidemic and helped save lives. Print can be very political, as a statement can be reproduced and spread easily. These statements can challenge authority and help to promote a society that is more just. A Black Lives Matter poster stuck on a lamppost is indeed art, politically engaging with the world around it.

Artists themselves often form collectives, or become members of organisations, that do not necessarily use art as its main means of radicalism, but for the purpose of informing, educating and drawing attention to important issues within a movement. Art can take on an important role within pressure groups or activist organisations, such as contemporary movements like Extinction Rebellion who use graphic art to display and promote messages.

Community

As well as art that demands change, in its own way art can become the change, with ‘community art’ and creativity that has a social focus. Ideas of cultural democracy (creative expression generated by citizens rather than institutions) has taken an important precedence in recent years. However, these spaces are disappearing and require funding to provide something real and valuable. When creating art for and with members of the public, the act of collaboration may be more important than what is actually created. It brings people together and gives a voice to those that are marginalised or oppressed. Producing this type of public art together with people, can in turn help work against gentrification or schemes that disproportionally disadvantage. Assemble is an example of an art collective that creates projects with and for people in certain localities, often by creating ‘environments’ like gardens and playgrounds. Sometimes artworks such as murals become symbols of a place’s identity, with people who live and work there taking ownership of the place and its culture. Which is why, if public monuments celebrate people who did not embody a society people wish to live in today, or actively worked to create a less just society, they are not appropriate to still stand in our streets.

Using art as a means of self-expression can never be underestimated. Organisations like Counterpoints Arts, who work with refugees and migrants, give a voice, as well as inspire inclusion and dialogue. Even arts therapy is a small example of something bottom up and often community led. Artists themselves may create collectives, to support creativity thriving in communities, which might revolve around pushing for space or funding, for example the Creative Land Trust.

These actions show that working collaboratively is arguably art’s most valuable tool. It is the best way to ensure that resources are more widely available and the needs of a community are heard and met.

When we create, we do something remarkable. Art has the power to go against the expected, freeing our minds from the constraints of a society where work and productivity supposedly determine our value. Ultimately, art is there to inform, inspire and sometimes imagine a new world. It should always challenge and unsettle, but it can also ignite change, facilitate change and demand it within its nature. Art should be joyous, to make, consume and be a part of. Sometimes, art may be our only source of information on a subject, because it calls that a group of voices must be heard. Sometimes, art can be the driving force of a movement, or be a vehicle for shared disquiet and collective action. Primarily, it should never stop making us think about the change that is needed or the change that we are capable of, as individuals or a society prepared to challenge, evolve, and progress.

Image Credit: Amplifer.com