Would it be ethical to give a patient suspected of a peanut allergy a peanut to eat to prove this hypothesis correct? To a certain extent, this is how I was diagnosed with vaginismus.

In a previous article ‘Why I feared penetration aged fourteen: Vaginismus’ I explain why painful penetration has been normalised. Vaginismus is a painful condition whereby the vagina tightens up just as insertion is attempted, the individual has no control over this. Upon realising that I owed my body a better explanation then ‘this is normal’, I visited my student medical practice. After describing my symptoms, an internal vaginal examination was established as necessary to deal with the suspected diagnosis of vaginismus. This is despite NHS guidelines stating an internal examination is ‘unlikely’ to be beneficial due to the potential pain and upset it could cause. Physical abnormalities or other conditions such as infections can be ruled out by visual assessment, with doctors needing to ‘take a quick look’.

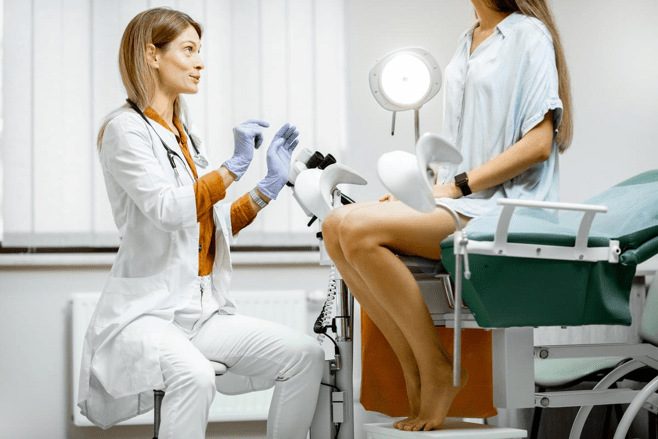

This was not my experience of diagnosis. I gave consent for the internal examination to take place. This decision was made because I thought an examination was mandatory in order to receive psychosexual therapy. I was given the choice of having a female doctor and a chaperone present. She attempted to insert the speculum whilst I was hysterically crying. Gentle pressure was repeatedly applied to my legs as I attempted to close them. When she was able to insert the speculum into my vagina to the smallest extent, she confirmed the muscle tension that she was expecting to detect. I then had to ask her to remove the speculum.

I am not a doctor and am writing this exclusively from a patient perspective. I am extremely grateful to live in a society where I can receive free public healthcare. Despite this, I find it hard to understand why a GP insisted on an internal examination when other psychosexual conditions, such as delayed ejaculation, are diagnosed by GPs listening to the symptoms described. Why did I have to experience insertion in front of a GP to prove it was painful? Why didn’t a trained doctor conclude that due to my obvious distress leading up to the internal examination, that an external examination would be better suited? Why not acknowledge that if indeed I did have vaginismus, that the internal examination could further reinforce my association of pain with penetration? At 19 years old I started worrying about future cervical smear tests. I would often become tearful when asked if I wanted to do a STI swab at the practice. My simple statement of ‘no thanks, I can’t use swabs’ was once replied with ‘oh it only goes in a little bit’.

It is impossible to approach this subject without acknowledging the current context of COVID-19 and the incredible work of NHS staff. I was given exceptional support once diagnosed and am very grateful for the therapy I received. However, this specific experience unearths a systemic issue surrounding how female pain and body autonomy is viewed and valued in modern society. These views have undoubtedly affected the prioritisation of services in the NHS, and the importance of holistic approaches to sensitive diagnoses should not be understated.

It is also incredibly important to acknowledge the privilege I have experienced as a white woman within the NHS. Stereotypes surrounding black female sexuality, of their representation as hypersexual and promiscuous (See Hart’s 2013 article), establishes a power imbalance for black female patients in healthcare systems. It is a common discourse that black women are more likely to have STDs; therefore their pain can often be dismissed. One need only emphasise the case of Loretta Ross- a black female reproductive rights activist who fell into a coma in the 1970s after being wrongly accused of having an STD for months. She was actually suffering from an unrelated infection (See Starkey and Seager’s 2017 article).

Relationships between GPs and patients intrinsically revolves around power. However profoundly wonderful and pioneering the NHS is, it has to be acknowledged that it was built within a society where power has historically stemmed from white men, especially in the context of medical diagnosis. It is this power to diagnose, and the notion that to comply with such a diagnosis means to offer up one’s physical body, that needs to continually be assessed and held to account. To what extent, and why, do certain people have to prove their pain is valid?

Ruby Campbell

For more information on topics discussed in this article see the sources below:

NHS vaginismus guidelines: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaginismus/

Hart, T. 2013. Constructing Syphilis and Black Motherhood: Maternal Health Care for Women of African Descent in New York’s Columbus Hill.

Starkey, M and Seager, J. 2017. Loretta Ross: Reproductive Justice Pioneer, Co-founder of Sistersong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective.

Image credit: Med Brief Namibia