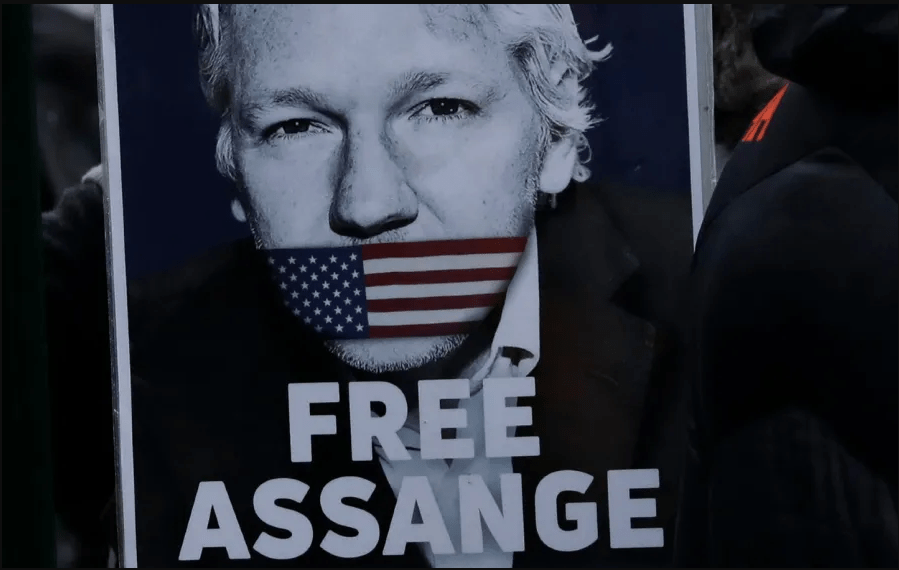

Few figures are simultaneously quite so feared and admired as Julian Assange. The WikiLeaks founder has had a long and tumultuous history in the public eye, as the legal battles and moral debates surrounding him continue to rage on.

Assange’s name was back in the headlines recently amidst rumours that the White House had attempted to broker a deal with him, allegedly offering to pardon him if he would publicly deny Russian involvement in the leaking of Democratic emails during the run up to the last election. Emails released by Wikileaks in 2016 proved hugely damaging for Hilary Clinton’s campaign – though rumours of Russian involvement in the leaking have long since haunted the current serving President. The WikiLeak was conveniently timed in the immediate aftermath of the release of a video that had appeared to show Donald Trump boasting of molesting women, detracting attention on the PR blunder from the Reds to the Blues.

Trump has denied any involvement in the attempt to liaise with Assange; eyebrows have been raised by the accusations nonetheless.

Australian-born Julian Assange founded WikiLeaks in 2006, as a platform that would allow sources and whistle-blowers to anonymously share their confidential stories, documents, images and videos. The website first caught widespread public attention in 2010 when it released footage showing US troops shooting dead 18 innocent civilians in Iraq, alongside a heap of classified documents detailing US military involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan and as many as 5 million confidential emails from US intelligence company Stratfor.

It was this exposure that really sparked the debate over whether WikiLeaks’s role as a whistle-blower was a noble effort to expose the truth and hold politicians to account or a public nuisance, releasing potentially life-threatening information, fuelling conspiracies and distorting views on the basis of what it chooses to publish.

Sentiments swayed more towards the latter point of view when, later in the same year, Assange became the subject of sexual assault allegations from two women in Sweden. In 2012, Assange sought refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy in the UK, in order to avoid his extradition to Sweden to face charges. Assange also feared that he would be extradited to the US on the charge that WikiLeaks had been involved in the unlawful publication of secret government files.

After 7 years in the embassy, a deterioration in the relationship between Assange and his Ecuadorian hosts saw his status as an asylum seeker revoked. In April 2019, he was finally arrested by British police for breaking his original bail conditions and is currently being held on remand in Belmarsh Prison; no longer a serving prisoner, but now a prisoner awaiting extradition.

While the allegations of sexual assault from Sweden have since been dropped, the US have upped the ante on Assange, filing 17 new charges against him under the Espionage Act for publishing classified military and diplomatic documents. Combined, the 18 charges Assange faces from the US could land him up to 175 years in jail. This year marks the start of what is likely to be a long and complicated legal battle, where Assange will attempt to block UK authorities from extraditing him to the US for trial.

WikiLeaks, who continue to market themselves as a modern-day Robin Hood for the truth, labelled the decision to file further charges against their founder as ‘madness’ and a malicious attempt to undermine the First Amendment. Interestingly, WikiLeaks has actually been nominated for the Noble Peace Prize on a number of occasions for its ‘promotion of human rights and freedom of speech’ – though not without controversy.

Assange further claims that allegations against him are politically motivated and part of an unwarranted conspiracy to thwart his efforts to expose the dark secrets of government.

Among the charges against him are conspiracy to hack into US Department of Defence computers, with the help of former US army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning (who, incidentally, is also currently in jail for refusing to testify against Assange). On the one hand, the US government’s anger is understandable, given that releasing classified intelligence could thwart defence efforts that rely on confidentiality to work.

On the other, there are few countries in the world that hold up First Amendment rights to free speech quite so highly and therefore the fact that the government are so keen to waive it in this case may suggest that they might have more to hide than they would really like to let on.

The fairest summation seems to be to conclude that the issue of Assange and WikiLeaks’s moral status isn’t quite as black and white as it is often made out to be. There are certainly cases where whistle-blowing works for the greater good, with its capacity to increase political accountability and prevent human rights breaches. However, exposing classified defence strategies or selectively sharing stories that favour certain candidates over others cannot necessarily always be justified on the same grounds. There is a fine line between help and hindrance when it comes to exposing the truth and, when crossing it can involve putting lives at risk, it is not something that can ever be taken lightly.

Image: Matt Dunham (AP)