Hunter X Hunter. The Seven Deadly Sins. Naruto. Titles such as these bounce from the tongues of eager fans as some of the most engrossing long-time manga and anime adaptations to date. Their plots are well-written, their philosophies complex; the atmosphere tense and action immense. However, if there was anything that could puncture such popularity, it is the aged and drained reality that women are still not approached as they should be.

As of 2020, we women are still witnessing either being hyper-sexualised or else side-lined to support the male characters that hog the spotlight. The stereotypes in anime that spring to mind are the lolicons, obvious fanservice, magical girls, stock shounen heroines and witless fangirls. With these stock characters in mind, it does seem to feel like talking to a brick wall when trying to convince outsiders as to why anime should be given the serious time of day. In terms of the over-sexualisation of anime culture, this may already have an interesting history as to why such representation has persisted. The earliest form of print culture in Japan’s history is potentially the practices of ukiyo-e. Established during the Edo period (1603-1868), ‘ukiyo’ was a concept of places known as the ‘floating worlds’ that encapsulated the paradoxical experiences of pleasure with transience – this being an ample way that one might describe the experience of going to the brothel houses.

The woodblock painting forms that encapsulated this lifestyle, depicting erotic scenes and beautiful courtesans from behind the scenes of Shimabara, Shinmachi and Yoshiwara could arguably be what continues to inspire print culture in Japan so many eras down the line. It becomes understandable then as to how and why female sexuality and sexualisation continues to swell at the heart of Japanese animation, it becoming seemingly rueful that this element cannot be taken away from how women are portrayed as this would cause the entirety of the anime industry to wither and crumble.

It is not a matter of diminishing female sexuality but balancing it. It raised the question why the intelligence and artistry behind the ukiyo-e has not been properly embellished in depicting femininity. Many a competent writer and scholar from Haruki Murakami to Judith Butler, acknowledge how much of female sexuality is about performance and agency; it is a weapon that veers into either misogynistic archetypes of self-gain or more empathetic ideas of survival. It is imperative that in order to value the body, we must also value the brain. We must revise and humanise how we perceive female sexuality, for eradicating and diminishing it only threatens to serve the misogyny surrounding expectations of how women ‘should’ behave. This is what makes the best of the women sketched in the anime frame: this listicle including those that are quick-witted, passionate and determined yet also afforded the scope to be sexually articulate – to know and earn it.

Moreover, just as what often makes the sports genre of anime so popular – such as with Free! And Haikyuu!! – is how we often witness broiling emotions, complex rivalrous dynamics and intense characterisation as a result of infuriating setbacks. This should be the case for women too. Women should be depicted as being allowed to strive for self-improvement and liberation; to not merely be concerned for the men in the game but also to burn for their own achievements and self-improvement. This lack of personal drive and ambition is what scraps many a long-standing anime from being recommended as feminist-friendly – Detective Conan’s Haibara Ai being arguably the only reason why one would give the series the time of day anymore. Even Shingeki no Kyoujin (Attack on Titan) spins on thin ice given how the ace Mikasa Ackerman is depicted as being so overly protective of the male main character as her love interest, these formidable characters being castrated by the idioms of their gender and prevented from fully embellishing their own agendas.

Thankfully, there are animations that are more celebratory of representing female authenticity. Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli productions have long been the centre of discussion for fair and inspiring female representation; Spirited Away’s Chihiro, Princess Mononoke, Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle alongside Nausicaa and Kiki being only a taste of feminine greatness. There are many other anime series that boast women of quick wit, ambition and sensual expertise – this range of the popular and underrated setting suitable examples for the industry to follow as we take on 2020.

GINTAMA

When the title is a play on the lead character’s name and the Japanese word for testicles, it would be understandable for one for underestimate Gintama for its impeccable comedic and dramatic potential. It plays on the crude and slapstick humour that is true to the Edo period in which the series is set, somehow managing to marry its ridiculous adaption of outer-space aliens being the first to discover Japan with a nuanced taste of foreign entities destabilising the security of the homeland. The women fall into and embrace this balance of tragedy and comedy. Kagura Yato poses as the loveable and physically formidable third member of the leading trio, but the ensemble of fleshed-out females is not rooted with her. Other revered names include golden yet temperamental Shimura Tae, protective and perverse Sarutobi Ayame; sexually conflicted yet samurai-hearted Yagyuu Kyuubei and impeccable representative of Yoshiwara itself, Tsukuyo – Courtesan of Death. The ensemble doesn’t even stop there; the anime being more admirable for being able to develop such a carnivalesque ensemble of women that are grotesque yet loveable; easy to invest in and determined to never be stuck in the binary.

THE WOMAN CALLED FUJIKO MINE

You may know her as accomplice, lover and rival to Lupin III, but even before The Women Called Fujiko Mine manifested it has long been acknowledged that the titular character has a whole mind of her own. Fujiko Mine may be a professional criminal, cat burglar, spy and seductress, yet she is far from any stereotypical temptress, with this 2012 series being determined to prove this. Whilst the Lupin III franchise has spanned many series and movies for many years and many audiences, Fujiko’s story is not for the light-hearted. The tone is significantly darker and racier, yet the explorations of sex are fuelled with questions of morality, identity and psychology. The sketchier aesthetic perfectly compliments the sketchy and elusive character, Fujiko being perhaps more fascinating for not having a tragic backstory, instead simply being an embrace of women with adventure and greed as part of their natural arsenal.

GEKKAN SHOUJO NOZAKI-KUN (Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-Kun)

Far more comedic and lighthearted in tone than the last on this list, Monthly Girls will hold a special place in your heart with it‘s charming sense of ridiculousness. This romantic comedy follows high-school student Chiyo Sakura as her crush on schoolmate Umetarou Nozaki leads her into helping him illustrate his weekly shoujo manga. This may not seem such an inviting premise for female representation, yet the main plot acts as a trojan horse for plays on character tropes and genre. Similarly to equally funny and fluffy Wotaku ni Koi wa Muzukashii (Wotakoi: Love is hard for Otaku), this anime embraces the embarrassments and mishaps that comes with experiencing first love, yet allows Chiyo to be so open and inquisitive that she befriends a whole cast of characters outside of her love interest. One might say that the anime then is able to adapt a true essence of love that is platonic – not a relationship between male and female that is ‘purely friendship,’ but rather one that is based on unions of minds, ideas and art rather than diving head first into lustful scenarios that will inevitably fall apart.

YAKUSOKU NO NEVERLAND (The Promised Neverland)

There has rarely been so terrifying and intriguing a depiction of female villainy as within this very anime. Child protagonist Emma is enough of a reason to want to watch the series as her buoyancy and determination are normally the given traits for the male lead in any given sports anime. Regardless, if we had to give a prize for a product of narratorial genius, then Isabella and her uncanny poker-face win with flying colours. The impeccable animation with its focus on scene timings, musical accompaniments and attention to expression make it a masterpiece of tension – an animated equivalent to Parasite if there ever was any. It is no exaggeration to call Isabella a truly terrifying foe – her poker-face and unnerving grace whilst selling off her beloved children causing you to think that she is in fact as monstrous as it gets. Despite this, it is a true credit to the writers that even Isabella can be conceived as a victim in this mess. This is not a story necessarily where there is scope for forgiveness and redemption, but it is understanding that nuance that allows the anime to grab our attention – highlighting women not in the brackets of their gender but as fighters to be the last contender.

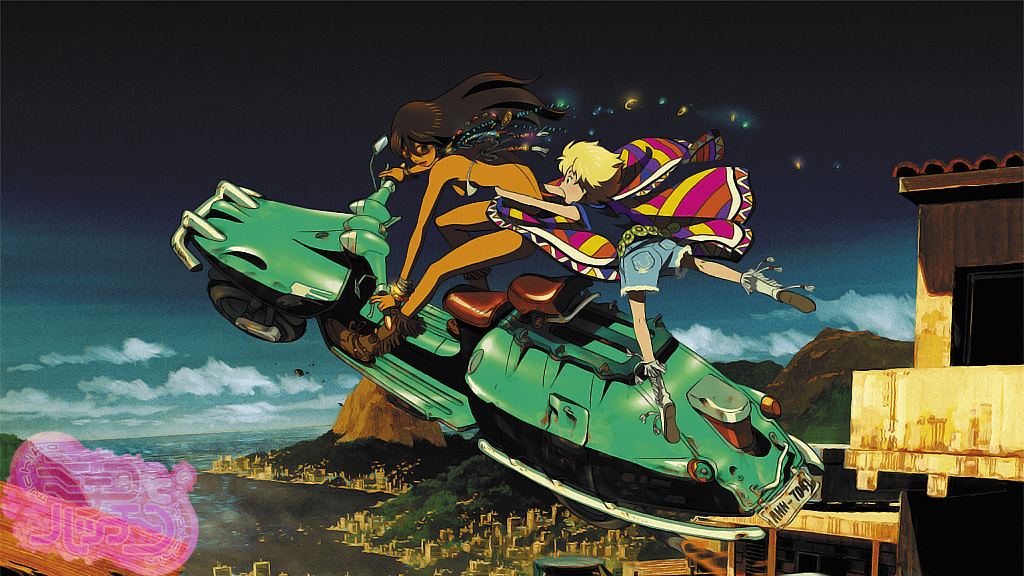

MICHIKO TO HATCHIN

You will be hard pressed to find decent anime that depicts ethnic minorities alongside complex femininity, but thankfully this package deal is available in the form of combo Michiko to Hatchin. Following escaped convict Michiko Malandro on the road with pet-named Hatchin – the supposed child of Michiko’s lost lover – this series upends and usurps everything you think you know about anime. With its gritty tone, focus on crime, bloodshed and embellishment of Latin American aestheticism, the show proves that anime has a cultural range that many studios fear to go. You might compare Michiko to Jessica Jones – each formidably moody and edgy with turbulent emotivity, Hatchin acting as a somewhat bratty foil whilst simultaneously being adaptable to the dangerous world around her. The quarrelsome duo make for an intriguing dynamic as you are never sure whom is the more empathetic or temperamental of the two. Theirs is a gruelling story of abandonment, mistreatment and rebellion, their dauntless partnership however outstanding against a backdrop of bleakness and corruption.

AKATSUKI NO YONA (Yona of the Dawn)

Last but by no means the least, here is anime with such outstanding female potential that the writers of Game of Thrones could take notes in their professional exile. Princess Yona begins as the product of many an irritating female archetype: a spoilt princess caught in the midst of a love-triangle, this being flipped swiftly upside down as her would-be love interest is responsible for her father’s death and taking over the crown. This forces Yona and her childhood friend and bodyguard, the ‘Thunder-Beast’ warrior Hak, into hiding whilst pursuing the myth of the formidable ‘four dragons’ who used to serve King Hiryuu – a member of Yona’s ancestry. Starting off as a typical shoujo comedy, it is remarkable how Yona’s characterisation is able to evolve with such finesse and subtlety. Her narration is like Daenerys meets Mulan – an embrace of the former woman’s insecurities and vitality, but like the latter, she is allowed to embrace her strengths as a warrior queen and embellish her influence over the male characters in her esteem. Yona is constantly haunted by the past yet still manages the strength to be compassionate, her journey allowing her to perfect her own combative skills as a formidable archer outside of Hak and the dragon’s protection. Unfortunately, there are only two seasons of this brilliant series available, yet the manga is still ongoing. Yona’s is a story that many a writer should find enviable – a demonstration of individual and communal power that the western world sees as tyrannical ‘madness’ instead of much needed female courage and independence.