Brexit might just be the most used portmanteau of the modern era; it might also be the most divisive. Nevertheless, Brexit Day has passed.

After three years of political turmoil, three prime ministers and four tense Christmas dinners marred by Brexit discourse, what do we have to show for it? Clearly a slick new word, with 622,000,000 Google search results to its name. And, of course, a Brexit deal and a transformed relationship with the EU.

As we look to the future, though, let’s go back to some of the most significant moments of Brexit that got us to this historic point:

The Big Red Bus, June 2016

This bus was full of promise. It embodies the referendum campaign, which pitted the present situation in the UK against the radical new ground of “leaving”. One side of the campaign presented leaving the EU as a vision of prosperity, the other a dark dystopia of recession. The promise of a better future certainly contributed to the electorate’s choice to venture into the unknown. They wanted change, be that “taking back control” of borders, or reallocating public funds. Therefore, 23rd June 2016 was a day of celebration for the Vote Leave and Leave.EU campaigners, who won over a bare majority of the public (51.9%). What they had voted for was Brexit. What that really meant was yet to be known.

From the start, this was clear. “Getting out of the EU can be quick and easy – the UK holds most of the cards,” said MP John Redwood, in July 2016. Now, over three years later, Redwood has witnessed the real complexity of the situation. Brexit has proven to be multifaceted: hard, soft, somewhere in between – like an ambiguous, ever-ageing cheese. It seems we didn’t even know what the cards in our hand looked like, let alone the game we were playing.

Bidding Farewell to Cameron, July 2016

In response to the referendum result, David Cameron resigned as Prime Minister. The referendum came about because it was made a feature of the Conservative party manifesto in 2015. The party feared that anti-EU sentiment from rival parties could lure their voters away, and there was increasing pressure from within the party to put forward a vote to ascertain the desired relationship with the EU. Cameron campaigned, unsuccessfully, to remain in the EU, and was succeeded by Theresa May. Recently he commented that he thinks about the referendum and its consequences “every single day.” It certainly defined his political career, and also marked the end of it.

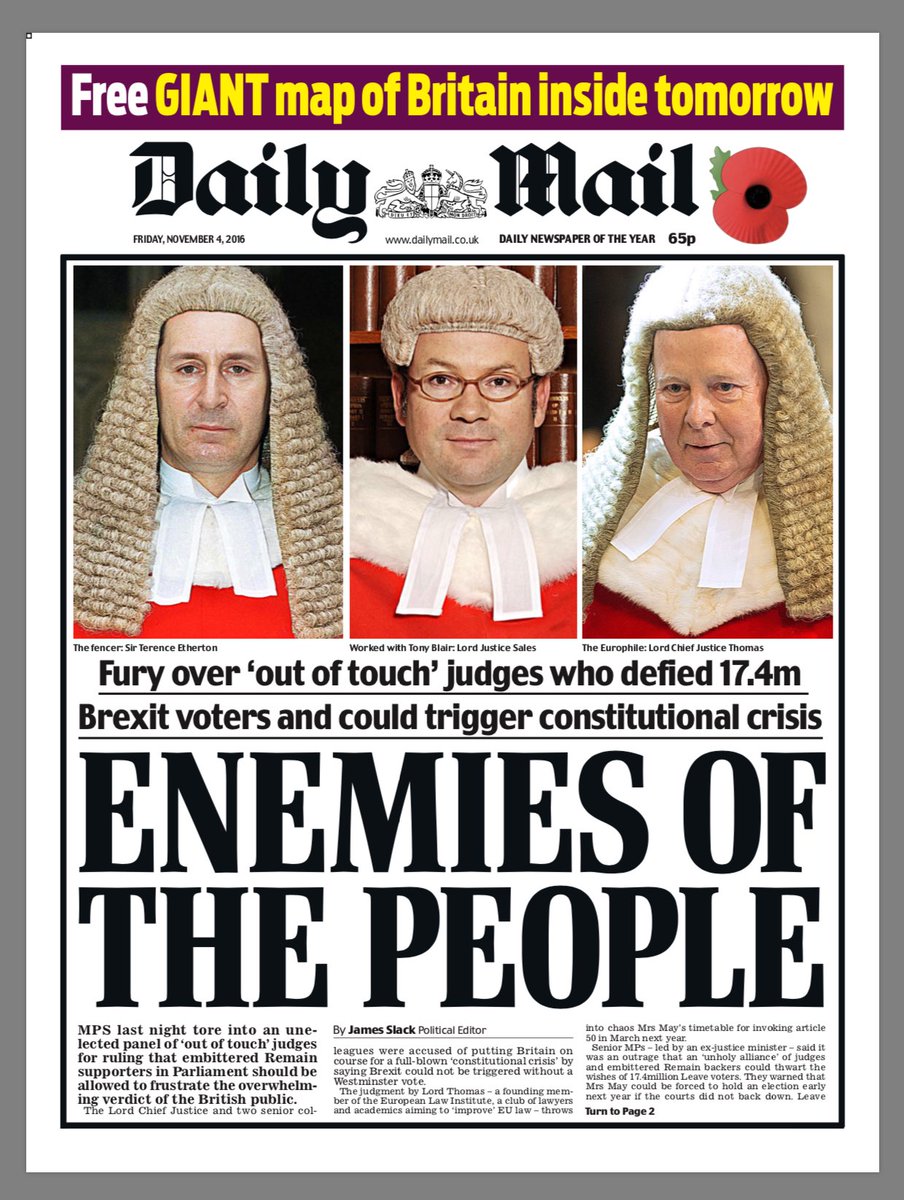

A Supreme Court battle…. and then another

Brexit began with a bang, which took the form of a Supreme Court case. It was ruled that the government couldn’t rely on prerogative powers to initiate the Brexit process, and that triggering Article 50 must be approved by parliament. This Daily Mail headline is poignant, expressing anguish at the judiciary for holding up the Brexit process. Yet it is ironic that they were deemed “enemies of the people” for ensuring the people’s representatives initiated the proceedings.

This wasn’t the only time Brexit related matters would find themselves in the Supreme Court. The 2019 case of Miller v Cherry declared Boris Johnson’s advice to prorogue parliament illegal. This was particularly controversial, as it is convention not to debate parliamentary matters outside of parliament. Some saw it as a judicial overstep with potentially far reaching constitutional impacts. Others saw it as an adequate response to executive domination. Brexit may be the union of two words, but this is the sole extent of its uniting effect. It has even exacerbated divisions in our understanding of the powers of the separate limbs of state.

The Chequers Plan, July 2018

The Chequers plan set out May’s proposals for Brexit in 2018. This included continued access to the common market and a new customs agreement, which did not require a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, nor any border in the UK. The customs agreement treated the UK and EU as if a combined territory. This deal was categorically rejected by the EU who said that May could not ‘cherry pick’ from the four freedoms, these being the free movement of capital, free movement of goods, free movement of people and freedom to establish and provide services.

May continued to pursue a Brexit deal. The Irish Backstop was a particularly controversial aspect of her proposals. It meant Northern Ireland would remain in some aspects of the single market in order to prevent the need for a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The deal was rejected by Westminster, with particularly strong opposition from the DUP, who argued that it diluted Northern Ireland’s UK identity.

Boris Johnson Arrives, July 2019

PM Boris Johnson swore he would rather be “dead in a ditch” than extend the Brexit deadline from 31st October 2019. Nonetheless, with a minority government, his attempt at a hasty exit was thwarted.

After all the talk of a new deal, his Brexit deal is relatively similar to May’s. One key difference is that the backstop has been replaced with a ‘front stop’, effectively creating a border in the Irish Sea, with goods being checked at ‘points of entry’ into Northern Ireland. Taxes will only be paid on goods being moved from Britain to Northern Ireland if they are considered ‘at risk’ of being moved into the EU afterwards.

After 46 years in the EU, we are leaving. Whether you see Brexit as a black cloud of doom or see leaving the EU as beneficial, there is a single certainty: things will change. EU law will no longer apply throughout the transition period, though we will remain in the customs union and single market. The government will pass a body of new laws to replace freedom of movement and EU legislation on environment, agriculture and trade. If a trade agreement hasn’t been reached by 31st December and Johnson has not requested an extension, the UK will then trade according to World Trade Organisation terms.

The immediate change after Brexit may not be overly stark for the average person – turbulence in the value of the pound, a slightly different selection of food in the supermarket, slower border control – but for better or for worse, our relationship with the rest of the world will be reconfigured, and the next 11 months will determine just how.

Image: Matt Dunham / AP