New research for the social mobility charity, Sutton Trust, condemns the new GCSE system for ‘disadvantaging the disadvantaged’ school pupils who are taking the exams in England.

New reforms to GCSE exams were introduced by Michael Gove and the government in 2015 and was enforced partly from 2017, completely from 2018. These included a move toward final exams rather than module focus, as well as a change in the grading system from letters (A*-G), to numbers (9-1).

These updates were intended to improve standards by increasing course difficulty, in addition to more differentiation at the top of the grade range.

Sutton Trust condemns the new system for ‘disadvantaging the disadvantaged’ school pupils who are taking the exams in England.

The report classifies disadvantaged pupils as those “eligible for free school meals (FSM) at any point in the six years up to and including the year in which they reached the end of Key Stage 4”.

The study shows that grades achieved by disadvantaged pupils fell after the new system, compared to their peers, by just over a quarter of a grade across nine subjects. These pupils were also less likely to get a 9 grade – with 1% achieving this compared to 5% of wealthier children. The charity says ministers must monitor the long-term impact of the reforms. The report – Making the Grade, by Professor Simon Burgess from Bristol University and Dave Thomson from FFT Education Datalab – assesses data from pupils at state-funded schools from 2016 to 2018.

It is at the grade 5 boundary where the negative effect of the new reforms on disadvantaged pupils occurs. “Non-disadvantaged pupils were 1.63 times more likely to achieve grade 5 or higher following the reform, whereas they were 1.42 times more likely to achieve grade C or higher beforehand. “This will matter if grade 5 rather than grade 4 becomes the expected standard for progression to post-16 courses or even in university admission.”

The researchers say 2% of disadvantaged pupils got the top grade (A*) under the old lettered grading system, in contrast to just 1% got a 9 under the new numerical system, for non-disadvantaged pupils, this stood at 8% and 5% respectively.

The report says: “Our central finding is that the reform has increased the GCSE test score gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils. The change is small, at an average of 0.02 standard deviations per subject, but is not trivial and is statistically significant. The results showed that the worsening of the gap is found among pupils with middle levels of prior attainment – those who were at Level 4 on average in Key Stage 2 reading and maths tests [Sats]. It concludes by warning:

“The overall result is clear: we find a statistically well determined effect, small but going in the direction of further disadvantaging the disadvantaged. So far at least, and although it could be argued that positive effects may take longer to come through, the GCSE reforms have widened the attainment gap, as young people move into the labour market or on to further study.”

CEO of the Sutton Trust James Turner said: “Our research tells us that the changes have likely had a small impact on the attainment gap, with disadvantaged pupils losing out by about a quarter of a grade across nine subjects. It will be important that the government monitors carefully the long-term impact that the reforms may have.”

The Conservative government defended its actions, saying: “Conservative education reforms are improving standards in our schools, meaning children can get a better start in life.”

Labour’s Education Secretary Angela Rayner, Shadow Secretary of State for Education, promised significant actions: “Labour will provide record levels of investment in our schools and increase education opportunities for every child, regardless of their background.”

Geoff Barton, General Secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said:

“The reality is that the students who struggle the most – many of whom come from disadvantaged backgrounds – have a very poor experience of the new GCSEs and leave school feeling demoralised about their prospects for onward progression to courses and careers. We are calling for an overhaul of GCSEs which improves the prospects of the forgotten third of students who currently fall short of achieving at least a grade 4 ‘standard pass’ in GCSE English and Maths.”

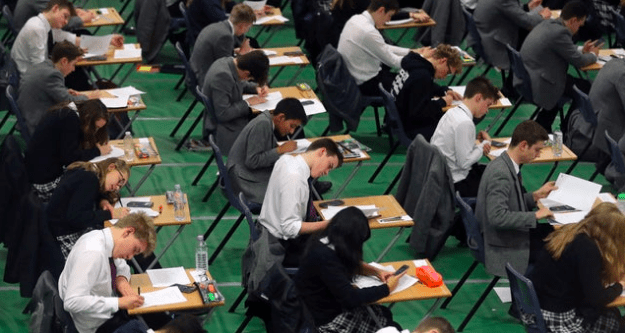

Main image: Gareth Fuller/PA Wire