There is nothing particularly groundbreaking about her style of prose, and the subject of adolescent romance is a time old classic. However, there is something about Sally Rooney’s writing that makes it physically impossible to stop reading. She writes about the adolescent experience with such sensitivity and respect, and is well-deserving of the somewhat crass epithet ‘Salinger for the Snapchat generation’.

‘Normal People’ follows the intertwined lives of Connell and Marianne from their final year of high school in sleepy Carricklea, to their last year at Trinity College, Dublin. Rooney introduces the economic politics of their relationship as Marianne lives in the ‘white mansion’, and Connell’s mother works as their cleaner. Although they are initially thrown together, Connell soon finds peace from their private encounters. Their differences are merely surface level: Marianne is both mocked and feared by her classmates, while Connell is popular but secretly exacerbated with his dreary life in Carricklea. Their relationship balances precariously between friends and lovers, as they come to understand more about each other and themselves. Their first significant rift occurs when Connell invites the popular girl to the school dance over Marianne for fear of his classmates’ reaction to their relationship.

At university Marianne finds her crowd of similarly rich intellectuals, while Connell finds himself isolated, wrestling with his feelings and finding an outlet for them. The two once more succumb to the carnal pull of each other but never quite realise what the reader has known since the first page, that they are made for each other. They merely break each other’s hearts over and over again, never quite managing to express their true feelings. The structure jumps forwards and back in varying intervals of time, adding layers to the narrative by showing it from both protagonists’ perspectives and highlighting to the reader how they always misunderstand each other at the most crucial times.

They are never quite boyfriend and girlfriend in the conventional sense, but they care about each other on a level their other partners fail to achieve. Connell struggles with his love for Marianne and attributes his inferior social class as the reason they can never be together. As such, he ensconces himself with a nice, uncomplicated but invariably dull girlfriend. Marianne, on the other hand, has numerous relationships with men who, unlike Connell, use her as an object for their own sexual gratification. I believe with Marianne, Rooney is speaking to a wider audience of strong-minded, fiercely intelligent women who are pathologically attracted to machismo. She has grown up with an emotionally absent mother and physically abusive brother and believes that is her lot in life. Marianne loves Connell but doesn’t understand how to be in a relationship with someone who respects and values her. Connell similarly struggles with the astonishing closeness the two have and the unnerving feeling that she would completely submit to him if he let her.

These characters are both desperately sad and lonely, who seek comfort from each other as their world bucks and changes before them. Rooney expertly captures the true heart-breaking agony of being in love.

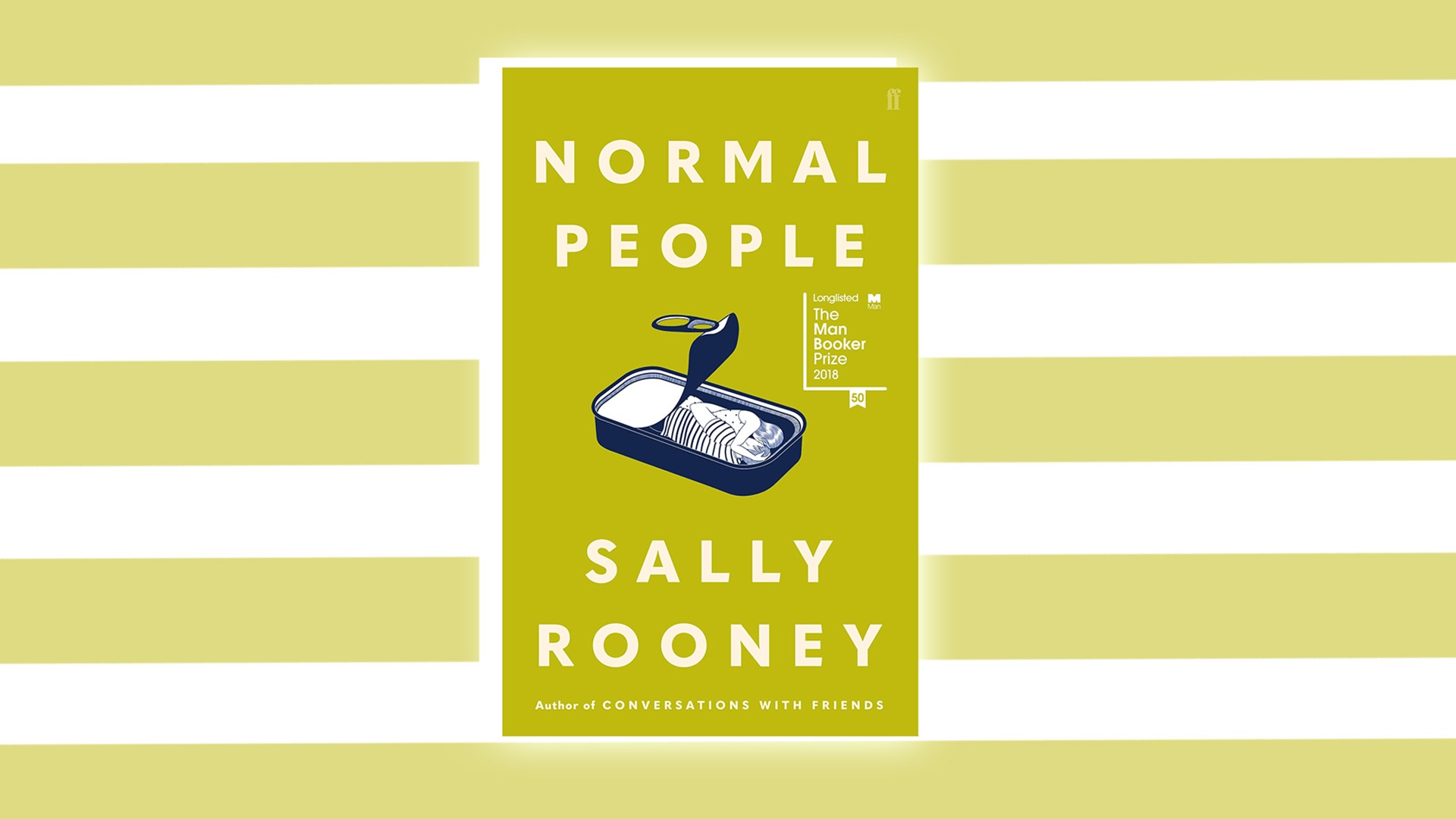

Image Credit: Vogue