The exclusion of the working class from the fields of arts and culture is nothing new. It Is impossible to deny the elitism of the film, TV, and radio industry when only a mere 12.4% of those employed come from working class roots. And so, in a creative industry that aspires to showcase diversity, why are the working class kept under a glass ceiling?

Statistics published by the Barbican’s report entitled Panic! Social Class, Taste And Inequalities In The Creative Industries revealed that less than a fifth of those employed in music, performing arts, and publishing came from working class backgrounds. This is further hampered by the fact that 96% of London’s creative workforce comes from socio-economically advantaged backgrounds. The predominantly middle-class composition of the field perpetuates the image of the creative industry as an old boy’s club, a sentiment that dissuades those outside this elite from breaking through. As 12.4% of the film, TV, and radio sector and only 12.6% in publishing come from lower economic backgrounds it is hard to overlook such a glaring class disparity. Yet the industry is still largely turning a blind eye: for all of the British success at the BAFTA Awards, 42% of winners attended fee-paying schools.

”42% of BAFTA winners attended fee-paying schools”

The lack of working-class presence in the field can be traced to the accessibility of arts education. The Warwick Commission report suggests arts and culture is being ‘systematically’ removed from state-school curriculum. The report highlighted that one third of gallery visitors and theatregoers came from the wealthiest 8% of the country, irrefutably signalling the correlation between wealth and arts access. This contributes to the diminished presence of working-class students at art universities and is particularly evident at dance and drama schools which demand high fees. Drama schools are known to have audition fees of £100 and that is simply to get a foot in the door, something which already prices out students from auditioning to multiple schools or even considering performing art as a financially viable education.

A Labour Party inquiry reported in 2017 that the topic of ‘class’ was often absent from discussions on diversity. The ‘Acting Up’ report concluded that performing arts were ‘increasingly dominated by a narrow set of people from well-off backgrounds’, making apparent there is no clear end to the barriers blocking working class mobility. If the working class cannot secure roles on stage and screen because of their background, then there will consequently be a failure to represent working class actors and industry leaders. This deficit denies relatable role models and continues the disenfranchisement of students to pursue careers in an industry statistically proven to be unwelcoming. Education is central to access and its reduction in less economically advanced areas enables the continuation of an artistic elite, a sector that remains seemingly impenetrable to those on the outside. Since 2010, there has been a 30% drop in arts subjects being taken at GCSE and, as the curriculum focuses upon the importance of STEM subjects, the appreciation of the value of creative education has seemingly diminished.

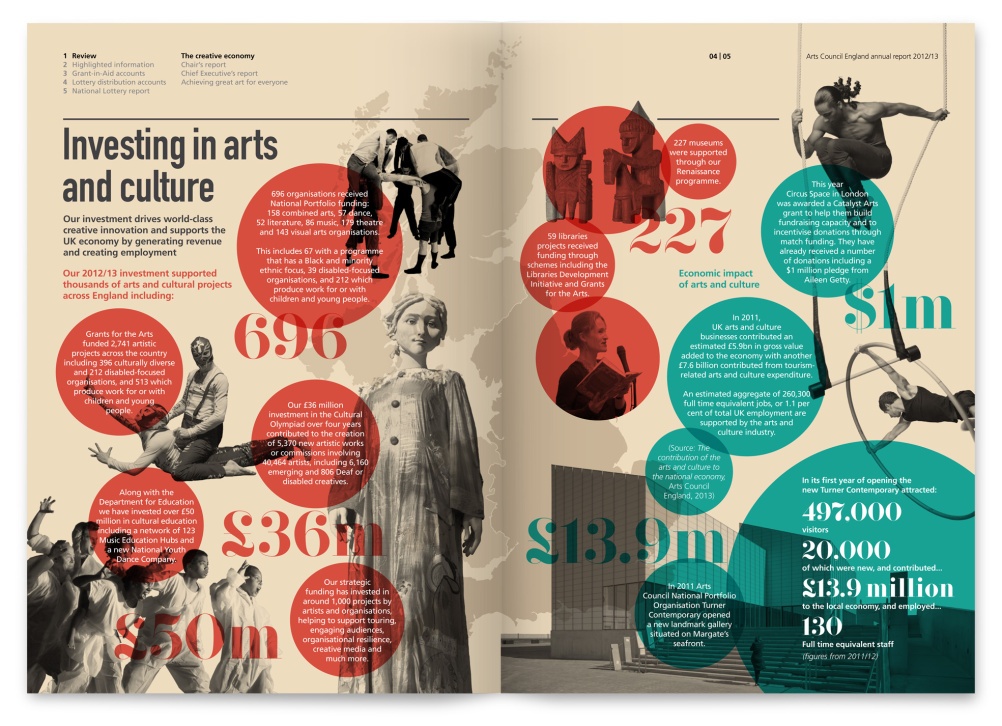

The damning report by Panic! led the Arts Council England, a group which distributes lottery funding to partner with the University of Leeds, in 2018 to investigate social mobility. The Arts Council undertook this partnership to produce an evidence base surrounding the possibility of social mobility as it recognised there was no current metric to measure social mobility. The group encouraged tackling class issues with the same vigour that has boosted the racial and gender equality in industry. As the Arts Council have investigated the evidence of class disparity, it is clear there are initiatives beginning to take social mobility seriously yet there is still a great gulf of accessibility.

With the release of multiple reports proving the relationship between class and access to arts and culture, it is impossible to deny the barriers facing the working class. The creative industry has seen drives for diversity in recent years and, as representation is vital to inspiration, it is time the industry confronted its own elitism and opened its doors to the working class. Changing the class composition of workers is not going to be quickly fixable, it is essential that arts and culture is funded for and encouraged at a school level as, failing this, the creative economy will remain stuck in a cycle of elitism oblivious to the diversity deficit blocking fresh perspectives.

Photo Credit: Design Week