A glorious concoction of musical nostalgia with intellectual intrigue, the Lincoln Center Theatre Production’s adaption of The King and I comes to Leeds Grand and proves a stellar opportunity to indulge in a night out of theatrical magic. Concerning the renowned story of widowed Anna Leonowens (Annelene Beechey) becoming governess to the children of the King of Siam (Jose Llana), Bartlett Sher’s direction evokes all the reminiscence of famous adaptions of the show that one may have fallen in love with in the 90’s and early 2000’s, whilst also channelling an astute sense of individuality that keeps you effortlessly invested in the play for its entire duration. However, it is additionally crucial to admit that it is difficult to enjoy such a show as The King and I without a postcolonial lens. Sher’s production indeed proves an apt example regarding whether we can really enjoy art purely as art without considering its political and cultural impact, and so if one wasn’t hooked to the stage out of sheer enjoyment, it was due to processing the possibly moral complications and questioning whether such a show can fit in our current society.

There were many positive aspects to the production as the aesthetics completely captivate you from the inception – the sight of the ship pulling into the dock of centre stage, the helm carrying the excited yet trepidatious Anna and her son Louis (Alfie Turnball) being a masterful display. The play fully embraces the beauty and sound of Siam through the Small House of Uncle Tom ballet in particular, whilst the veil of tumbling wisteria that sets the scene for the secret meetings between Tuptim (Paulina Yeung) and her beloved Lun Tha (Ethan Le Phong) encompasses an ethereal sense of the romantic with hues of oncoming tragedy. The music and renditions of the infamous soundtrack were impeccable, for whilst favourites like ‘Shall We Dance?,’ ‘Getting to Know You’ and ‘I have Dreamed’ were as emotive as could be expected, it was perhaps ‘Something Wonderful,’ sung by Lady Thiang (Cezarah Bonner), that proved a particularly rich jewel where Bonner’s voice seemed to fill up your soul.

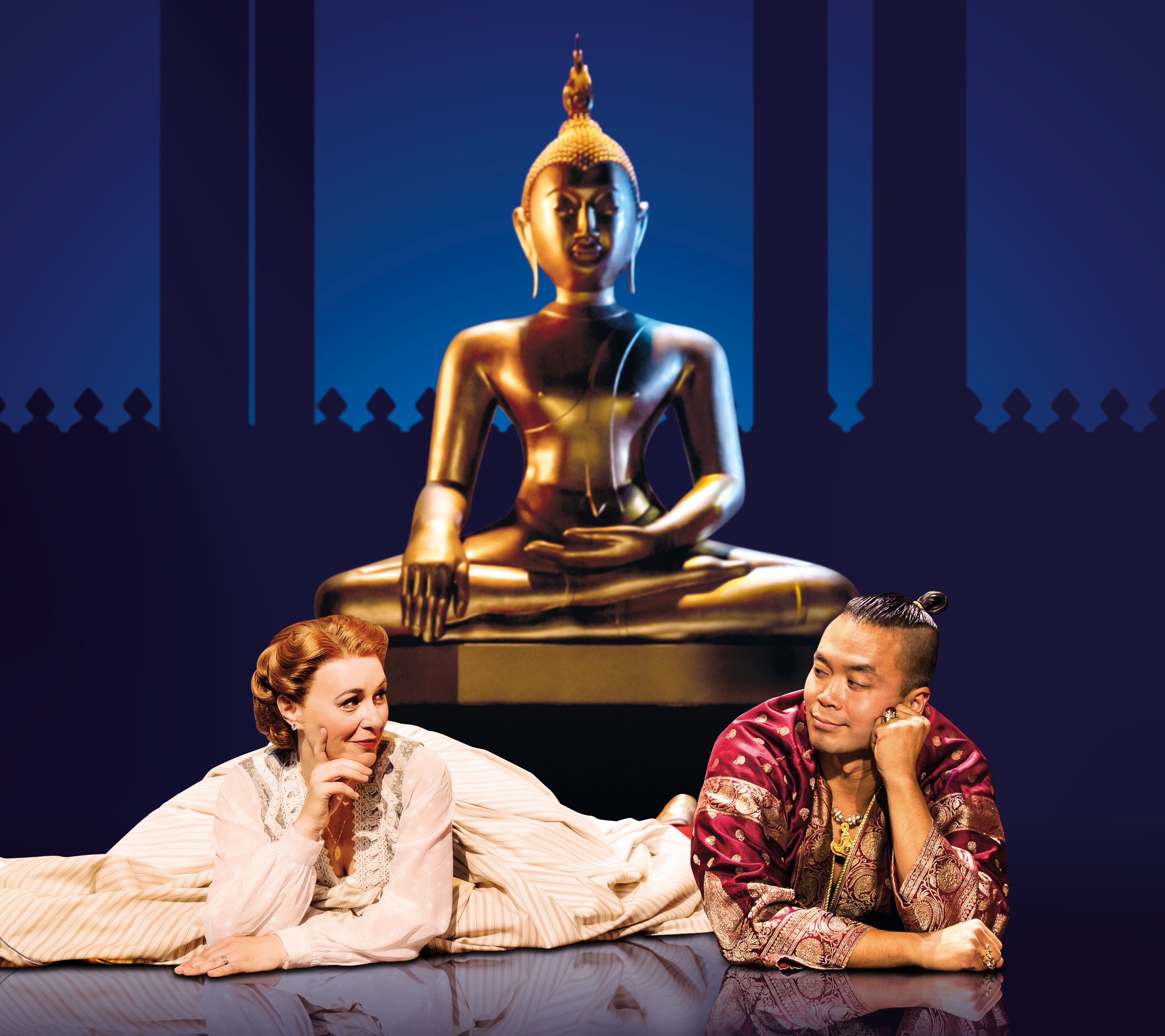

In fact, it is arguable that Lady Thiang is a fairly overlooked character in The King and I, however the way she was adopted by Bonner allowed her to become an outstanding, empathetic presence alongside Beechey’s Anna – so much so that their relationship was as near engaging as that of Anna and the King himself. It is undoubtable then that Beechey and Llana’s chemistry fires the heart of the show; blue and red oni that always titillate somewhere between confidantes, rivals and intimate friends with the promise of something more. Llana in particular stood out in the relationship as his struggle between humanism and trying to bring his country into a state of modernisation is incredibly palpable; the wit, sardonic charm and hilarious impatience that Llana enlivens in the King being what makes his character all the more stimulating.

Having said this however, the second half of the play arguably actively critiques the stereotypes that emerged in the beginning, this being cleverly implied by how it opens with Lady Thiang’s more derisive number ‘Western People Funny’ and the hilariously hyperbolised montage of the King’s wives struggling to adapt to Western make-up and attire. It becomes more evident as the action unfolds that Anna indeed relies on the peoples and culture she has grown to love as much as the King relies on the knowledge and innovation which her presence symbolises, the final scene with her bowing to the new King (Aaron Teoh) and being surrounded by the children perhaps being an image which we should embrace on grounds of equality rather than the potential for it to be divisive. In the same vein we could argue that the House of Uncle Tom sequence may be an inappropriate example of parading the culture of Siam before Western eyes (as that is indeed the situation in the play itself and the audience then becomes implicated in turn), or we can praise the piece for exploring the passions of Siam and creating a sequence that may do justice to the peoples and culture. It is fair to say then that although there is much to be answered for in this adaptation, it is clear that Sher and the cast have done their best with the material they have.

Essentially The King and I causes us to ask whether such a play should still exist on stage at all if it perpetuates potentially offensive messages for the sake of art and aesthetic, especially as it is not clear whether the adaption meant to risk its own validity in order to make a social commentary or was merely focused on the play as a piece of theatricality. Despite this, the play is still an undeniably enjoyable and escapist experience; a showcase of impeccable talent alongside invigorating thought and conversation for those of a more socio-political palette.

By Tanika Lane

Images courtesy of Leeds Grand