The exhibition, ‘Edward Allington: Things Unsaid’, begins with the quote: ‘Sculpture is looking at real things by making real things. It is making poetry with solid objects.’ (Allington, 1997). This quote perfectly captures the essence of the exhibition because Allington’s art is as timeless as it is deceptively simple. At first glance his artwork appears modern and unambiguous, but upon closer inspection, the classical influences and subtly hidden meanings become more clear.

Edward Allington (1951 – 2017) was a man of many talents. He was a writer, sculptor and educator but was chiefly known for playing an instrumental part in the 1980s New British Sculpture movement. This movement changed the British sculpture scene by responding to the changing aesthetic, social and cultural values through a combination of pop and kitsch elements and through exploring how objects are assigned meanings, amongst other themes. Allington’s artwork is exhibited in significant collections including those at Tate, The British Museum and The Victoria and Albert Museum.

The exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute is divided into two sections. The first focuses on Allington’s art and the second, across the bridge in Leeds Art Gallery, presents a selection of archival material pertaining to sculptural progress, works outside of the exhibition and Allington’s own writings. The division of the gallery allows for a sense of progress, a feeling of delving deeper into the art and its meaning, to probe into the behind-the-scenes of Allington’s creative process. It is clear, upon entering the exhibition, that the layout of the artwork is representative of the art itself. Pieces such as Unsupported Support (1987) and One of Many Fragments (1988), both of which resemble parts of classical columns, are placed high on the walls to emphasize the missing parts. The piece Fallen Cornice (1993) is designed specifically to fit into the area and so it surrounds the room, transforming the entire space into a sculpture itself. The layout of the exhibition isn’t its only success, however. The exhibition also contains many quotes by the artist which add a personal touch to the display, illustrating Allington’s artistic intent as well as showing his literary talent.

Furthermore, the exhibition focuses on the relationship between perception and reality which Allington explores through the presence of classical forms in modern life. By utilizing classical iconography, he prompts a question surrounding emulation and authenticity. One of the pieces that perhaps encapsulates this best is Ideal Standard Forms (1980) which is situated to the right as you enter the exhibition, and immediately draws the eye to its simplicity. The sculpture features nine separate geometric objects arranged in a square on the floor, and while seemingly uncomplicated, it actually alludes to the ideology of Plato. Allington echoes Plato’s sentiments by referencing the ethereal forms of his philosophy yet he also rejects his notions of originality. Through creating shapes by plastering over clay forms and then removing the clay he leaves an imitation, something unoriginal. All of Allington’s pieces in the exhibition are similar in this respect. They hint at a hidden depth and ambivalence whilst on the surface remaining resolutely impervious.

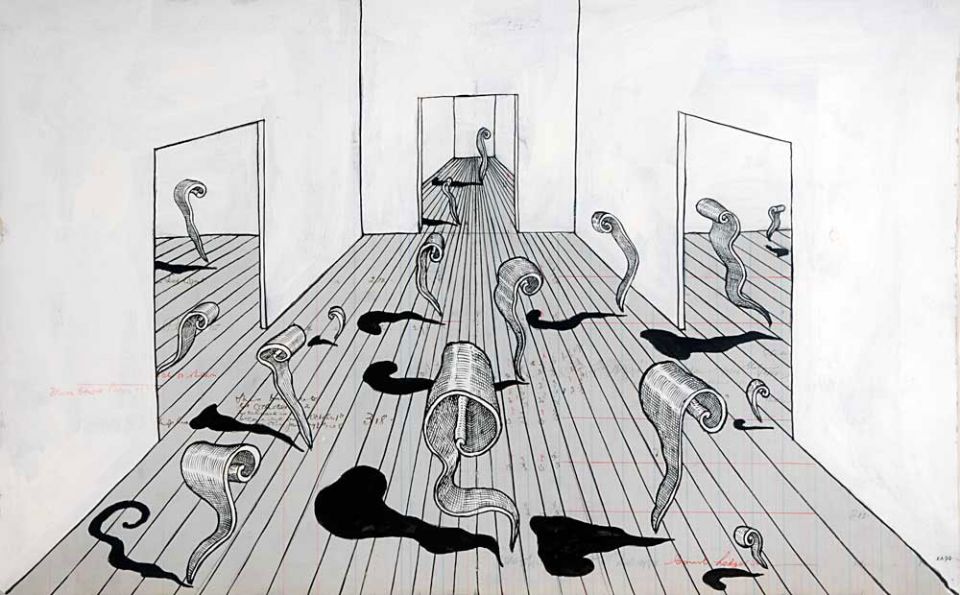

The title of the exhibition is taken directly from a drawing by the artist in the Leeds Art Collection. Things Unsaid (1990) suggests that we know and keep secret more than can be spoken. This is illustrated in the drawing by depicting scrolls of writing as people moving through rooms alone. The piece evokes a surrealist style which is reflected in most of the pieces in the exhibition and emphasizes how, in Allington’s artwork, there is always more than meets the eye.

Photo Credit: Henry Moore Exhibition