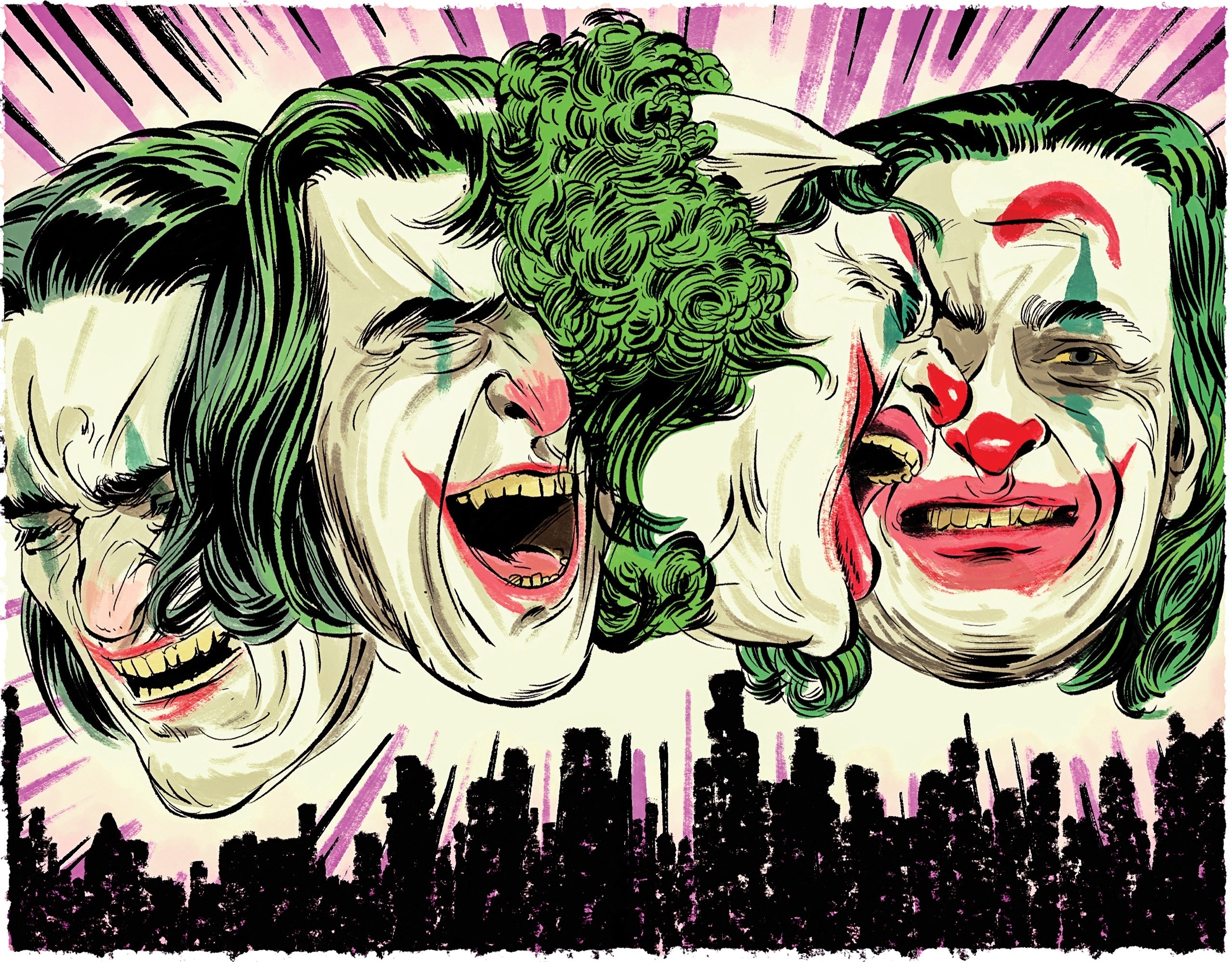

Don’t get me wrong, I loved The Joker. I thought it was a brilliant depiction of what happens when political elites neglect the societies that they are meant to serve – and then for them to have the audacity to turn around and claim that they, with all their wealth and wisdom, have the remedies to fix the system of depravity that they helped pervert. I’m looking at you Thomas Wayne, and for that matter, Howard Schultz. However, even the most extreme interpretations of latest DC comic book film cannot seriously describe it as being truly radical. Yes, the way it deals with the issues of poverty, mental health and INCELiness has been seen as extremely controversial. For me though, it doesn’t break the mould of a normal, albeit extremely bleak, Hollywood film.

Bait by comparison, is nothing like The Joker. Released on the 30th August 2019, Bait is a short production which examines the tensions between a small Cornish fishing village community and its newly immigrated tourist population. Shot on 16mm film with a near ancient Bolex cine-camera, the scratched monochrome production and the dialogue overdubs give Bait a feel of a film not belonging to this century. Moreover, it’s budget would’ve barely constituted a drop of water in Hollywood’s vast financial ocean. So, why bother bringing these two films together to share the same page if they are clearly so different? Firstly, I saw them in quick succession. Secondly, I believe that Bait, with its tiny budget and eerie cinematography has a far more radical and relevant message to our current political predicament.

”Bait, with its tiny budget and eerie cinematography has a far more radical and relevant message to our current political predicament.”

At the crux of Bait is the drama that unfolds within and between a family of village fishermen and a wealthy family who have bought up properties in their village for tourism purposes. In the aftermath of their father’s death, the two sons of the fishing family are divided on whether to use their small boat and family home to cling onto a declining fishing industry or to succumb to the seasonal stag dos and scenic boat tours of the emerging tourist industry. Steven Ward (Giles King) takes the family boat into the tourism game and sells the family house to the newly immigrated residents in order to support his family. Martin Ward (Edward Rowe) on the other hand, stubbornly sticks to his family’s fishing roots and berates his brother for not doing the same. Martin holds the new tourist landlords in contempt, seeing their arrogance and condescension as further encroachments upon his already precarious existence. A melodramatic form of tension and tragedy ensues.

Bait’s social message is a stark examination and critique of the very real crisis’ that Cornwall’s communities and coastal towns across the UK have faced in the past 50 years. The declining primary industries that once formed the backbone of the UK’s industry might have been replaced with seasonal tourism and service jobs with stagnant pay. Meanwhile, Britain’s cities have been booming. A recent BBC study found that workers in Britain’s coastal areas earn on average £1,600 less per year than those living inland. The growing economic inequality between coastal and inland areas has fed an insatiable appetite for the buying up of seaside second homes by a class of wealthy city dwellers. Like many other areas, this has had the effect of raising Cornwall’s house prices and subsequently pricing out younger local residents. With affordable housing and well paid jobs rapidly becoming rare commodities on Britain’s coasts, it becomes almost imperative for those with the right skills and education to move inland, facilitating a brain drain and so further perpetuating the decline of coastal communities. As of 2019, four in ten coastal towns are forecast to suffer a decline in their population of under-30s, with those in the north affected the worst.

Power and autonomy has now firmly shifted from the coastal communities themselves into the hands of the ‘landed and the second-home class’. The essence of this phenomenon is perfectly distilled in Bait’s narrative, with the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw correctly observing that it is now the wealthy outsiders who hold the nets, the community and its beautiful landscape who constitute the bait, and the locals who are caught in between.

Like many coastal communities in Britain, Brexit was packaged and sold to Cornwall on the basis of alleviating many of the issues held responsible for their decline. Frustration with EU regulations surrounding primary industries, namely the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy, as well as a perceived difficulty in accessing EU funding are some of the major reasons why 56% of Cornwall voted leave in 2016. From this perspective, leaving the EU would liberate the area from a politically elitist centralised power structure which was seen to be hampering its development and maintaining its dependence on unstable tourism. However, just as there has been no pledge from Brexit MPs to finance the NHS with the money saved from the EU, there has also been no government commitment to replace the £60 million in EU aid which Cornwall receives annually. It is clear from a recent interview with CornwallLive that the region’s MPs remain optimistic about the opportunities posed by Brexit. However, with the proposed exit date looming, the future of Britain’s seaside towns looks more precarious than ever before.

Obviously, attempting to extract coherent political messages from film, that aptly describe our current discourse, will always be of a limited effect. The majority of film, especially Hollywood blockbusters, are made to entertain and be lucrative. On the other hand, film, music and culture is not produced in a vacuum. I think the line that threads through Joker, Brexit and Bait is simply the sense of anger felt by ordinary people, towards a dismissive political establishment. Whereas The Joker conveys this in a dark fantasy, Bait communicates it in stark notions of political reality.

Image Credit: MovieWeb