In recent years, there has been an increased push for diversity, of all kinds, in the workplace, whether that be in business, marketing, education or public institutions. The public are tired of air-brushed pictures of slender women and images of White, heterosexual families. In a survey, 71% of clothes shoppers preferred retailers to use more diverse models in marketing campaigns, proving consumers want to see more women, LGBT and BAME people represented.

The media has responded to the increased demand for diversity, with marketing campaigns such as Sport England’s ‘This Girl Can,’ Absolut’s ‘Equal Love’ and Channel 4’s ‘Advert Takeover.’ These advertising campaigns include people of all races, sexualities and genders, with a view towards promoting greater inclusion and acceptance in society.

But while the use of diversity marketing is flourishing, it is not reflected in these companies’ workforces. Despite using a range of people in their advertising, the boardrooms of top companies are as White, male and straight as ever. At the most senior level of corporate leadership – Chair, CEO and CFO – 96.7% of individuals are white and 92.4% male. 48% of FTSE100 companies still have no non-White board or executive committee members and there are no non-White women who have ever been CEO of a FTSE 100 business.

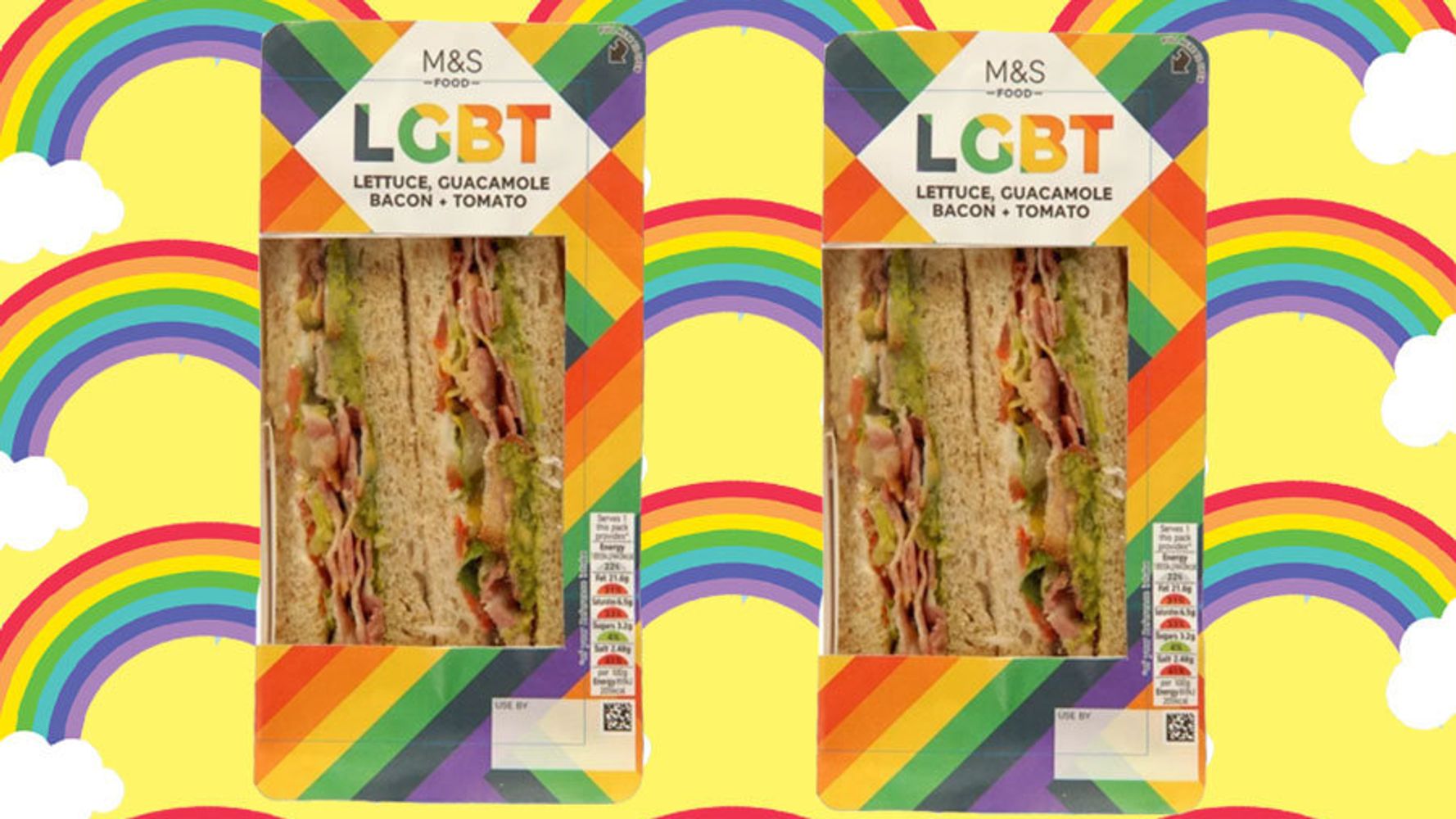

To make matters worse, many companies display solidarity for marginalised groups on social media or in marketing campaigns, drawing attention away from their internal representation. Businesses were accused of ‘pinkwashing’ during Pride, as they changed their logos to the colours of the Pride flag, then quickly reverted once the month was over. More than one in seven FTSE 100 firms who changed their Twitter logos to support Pride month in July did not mention LGBT+ at all in their annual report. LGBT+ staff are paid 16 per cent less than their heterosexual counterparts, and the rate of LGBT hate crime in the UK rose by 144% between 2013-14 and 2017-18.

Companies and institutions are willing to pay lip service to minority groups because they view diversity as a marketing tool. They know that people who see themselves represented in their advertisements will be more likely to buy their products. It is evident that the people profiting from diversity campaigns are not the people that the campaigns represent.

Some businesses, however, do feel pressure to respond to protest over their lack of internal diversity. Google spent $114 million on its diversity program in 2014; yet, its diversity report showed that black people made up just 3.3% of its workforce and held just 2.6% of leadership roles.

Continual failure does not cause many institutions to change their tactics. Lauren B. Edelman, a professor of law and sociology found that courts tend to look for symbolic structures of diversity rather than their efficacy. The diversity apparatus does not have to work – it just has to exist – and it can help protect a company against bias lawsuits, which are difficult to win.

Even if marginalised groups are employed by these businesses, they often function as tokens and are expected to remain silent. Companies do not want to hear their voices and innovative ideas, but their presence is used to prove that the company is ‘progressive.’ 28% of BAME employees have experienced or witnessed racial harassment from managers in the last five years, revealing that inside corporations little is changing.

For people who rarely, if ever, see themselves reflected in the media, any representation can seem like a positive. Representation can be a tool to empower and inspire confidence in marginalised communities but, until change is implemented within the organisations themselves, diversity will just be another promotional tool lining the pockets of the established elite.

Image Credit: HuffPost UK