The Gryphon looks at Blondie frontliner Debbie Harry’s new memoir and its candid discussion of her career, violent encounters, domestic abuse and her status as a sex symbol. Warning: this article contains references to rape which might be disturbing to some readers.

Debbie Harry’s new book ‘Face It’, released earlier this month, is set to be a thrilling memoir of the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll-fuelled rollercoaster ride that was the now 74-year old Blondie lead singer’s illustrious career. In many ways, Harry might be the role model every young feminist dreams of: tough, tenacious and independent. She has sex with who she wants to have sex with, and spends time off from tours residing happily in New Jersey with four dogs for company.

However, being simultaneously a sex symbol and a feminist icon is no straightforward endeavour. Is it really possible to be both? The feminism of 2019 seems to say yes, but the question of how one ought to go about navigating a world where we are told every approach is the right one can be a difficult one to grapple with.

Rape, domestic abuse and violent encounters are all topics that Harry speaks about in the biography with a casualness that verges on being disconcerting. When describing the ordeal she suffered in the early 70s of being chained to her bed and raped while her then-boyfriend Chris Stein watched helplessly, she claims that “In the end, the stolen guitars hurt me more than the rape.”

Harry’s flippancy here treads a fine line between making her a symbol of empowerment, and normalising the atrocity that it is to suffer a rape attack. At the end of the day, her making light of the situation is a coping mechanism – something to do with taking power back from her perpetrator – but it’s a controversial approach to take nonetheless.

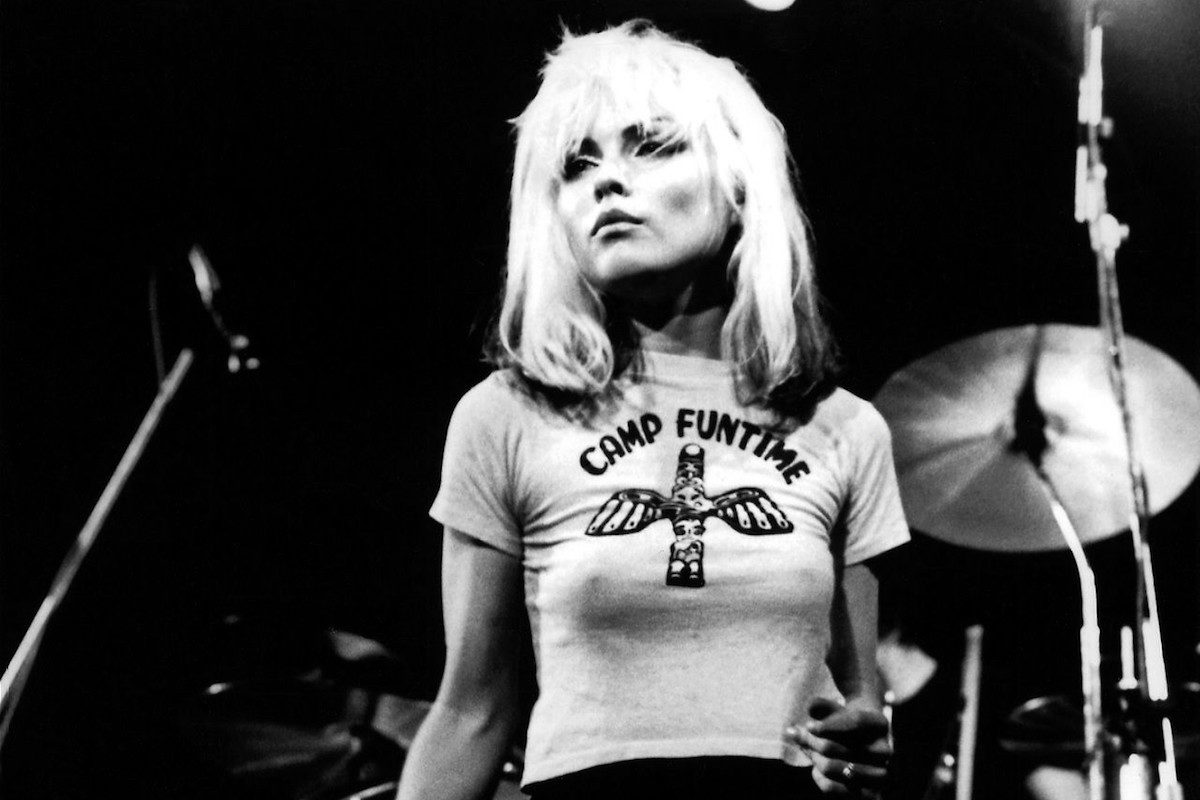

In Blondie’s prime, Harry was very much a lone woman in a man’s world.

Arguably, few women in history have been lusted after and objectified to quite the same extent. Did it bother her? Only if it wasn’t on her terms. A former Playboy bunny, Harry played into the attention she got, capitalising on it, even. Surely there is no better way to take power away from the patriarchy than from profiting off of its misogynistic tendencies?

Where Harry draws the line is the point at which this power is taken away from her. She famously got into a row with her record label after a photo was published of her in a see-through blouse – sans approval. ‘Sex sells,’ she admits, ‘but on my terms. Not some executive’s.’

It’s a tempting position to adopt, but finding the right balance of promoting sexual liberation without fuelling the kinds of objectification and misogyny that led to ‘Me Too’ is no easy feat.

One might worry that Debbie Harry using the sexualisation of her image to drive record sales is still playing into the hands of the patriarchy; even if it is her own choice to do so.

The same questions around sexual freedom arise when it comes to the topic of pornography. In 2017, Pornhub found that a quarter of searches by straight women were for violence against their own sex. Is the preference for violent porn really an independent choice, or is it a consequence of internalised ideas of misogyny that we are subconsciously absorbing from the world around us? Trying to decipher the origins of our own choices is no easy feat, especially when they might be rooted in some sort of strange Stockholm Syndrome.

Today’s feminism holds freedom of choice up above all else. If a woman wants to choose to watch violent porn, feminism says she should be free to do so. But the question of how getting turned on by misogyny fits in with the movement whose primary goal is putting an end to it is not an easy one to answer. These are the sort of complex questions that feminists of 2019 often have mixed views on.

Whilst Debbie Harry’s method of storytelling potentially trivialises sexual violence, the carefree approach she takes when it comes to some of her other choices ought to be emulated. If you want to watch violent porn, shave all your hair off or be a Playboy bunny, then I would lean towards the side of telling you to go and do it – misogyny and toxic gender norms need addressing on a much more systemic level and it isn’t our constant responsibility to use personal choices like these as the tool with which to abolish them.

Unfortunately, setting standards for feminism too high only risks fracturing a movement that ought really to be defined by support and inclusivity. Taking down the patriarchy is tiring, and sometimes you do just have to pick your battles.

Image: The Rake