People on the net may be familiar with the “This is Fine” meme. It is about a dog surrounded by flames yet commenting that everything is “alight.” K.C. Green, the artist, later drew a follow up on 2016 titled “This is Not Fine.” The dog goes about putting out the fire and breaking down into tears. It is reported that Green had never wanted his satirical comic to be treated as a meme to excuse horrible events in life.

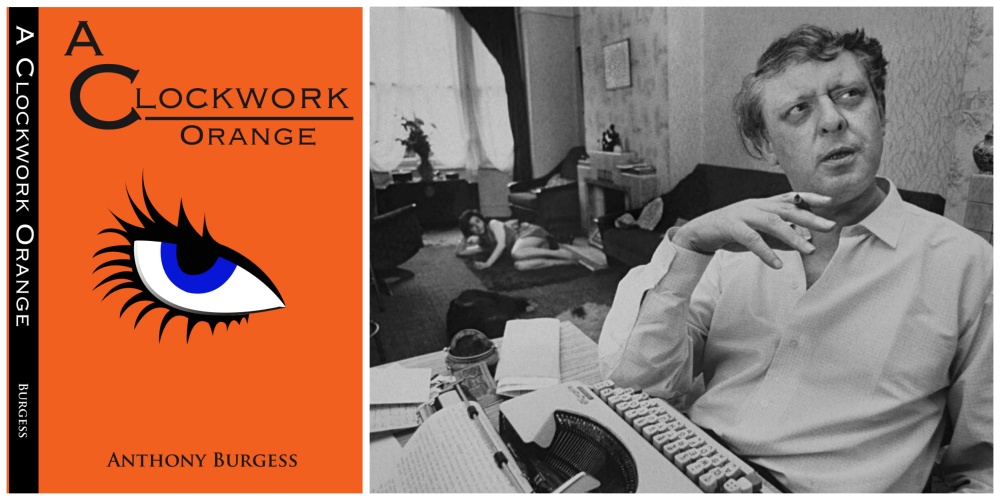

Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962) follows the same suit. A Guardian article, published on 25th April, wrote about the discovery of an unpublished manuscript that served as a sequel to the literary classic. It was a culmination of attempting to respond to the film hype of A Clockwork Orange (1971) and all of its discontents. Stanley Kubrick made the protagonist Alex immortal in cinema; yet the film got a bad reputation, as many TV shows today, of helping to encourage violence and societal disruption. Needless to say, Burgess was not too happy about this as his work was meant to critique societal degradation not heighten it. He had been working on a novel called “The Clockwork Condition” to illustrate aspects of his former book and the responses to the film’s adaptation.

The Guardian reported he abandoned his attempt on the manuscript as he felt the sequel carried too much of a philosophical quality and he simply considered himself an author. The Clockwork Testament (1974), which in my opinion sounds more philosophical than “The Clockwork Condition”, was published as a loose sequel to his famous work. It is part of other novels featuring the character of Enderby, whose predicament seem much like the author himself. A reserved man who is pulled into stardom and later almost killed for it. The novella itself reads as an exaggeration at times. There seems to be no filter and no “devil’s advocate” just plain critics and spiteful people who hate Enderby for scenes in a movie adaptation of a poem that had nothing to do with him.

It is always interesting to see authors publish works in responses to the consequences of a former one. It is not uncommon yet it is not the norm. And, as with movies, sequels tend to be treated suspiciously. Take Harper Lee’s Go Set A Watchman (2014), the following novel to the beloved To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). Critics and fans alike were disappointed that their hero, Atticus Finch, was not who they wanted him to be. Lee’s novel was always about Scout; both novels were to be treated as of coming of age novels for the girl and woman. Yet, Atticus took the spotlight and his eventual “decline” is unceremoniously treated as the decline of Lee’s understanding of the novels.

It is easy to hold onto works or label them as “failures” when we feel certain subjective standards are not held. It is also common for authors not to write follow up works for similar reasons. Nowadays, authors can, if they wish, answer to qualms on Twitter (or block people for asking questions at all as the rest of us mortals). They do not need to labour on a response. Yet how we take novels and their responses seem to usually lie on our preferences rather than holistically taking them as products of their time. Margaret Atwood will be publishing The Testaments later this year, which is a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). The usual fare may presume: some may love it and others may feel that the original work has lost its sheen. Either way, writers gonna write. And, so it goes.

Zarin Rafiuddin

Image: Briff.me