If you’ve had little prior exposure to economics, then the word might conjure up images of fusty, grey professors, wearing tweed and agonising over pie charts whilst using words like ‘hypothecation’. And that’s all (mostly) true. But despite its enduring reputation as the ‘dismal science’,by contrast to ‘cool’ sciences like marine biology, economics has a vital role to play in debates surrounding our use, overuse, and misuse of the world’s resources. The question of sustainability has been on economists’ minds ever since Thomas Robert Malthus suggested that the world’s population grows faster than our ability to feed it, back in 1798. This October, two economists won the Nobel Prize for their pioneering research into sustainable economic growth, and how we might avoid this bleak vision of the future.

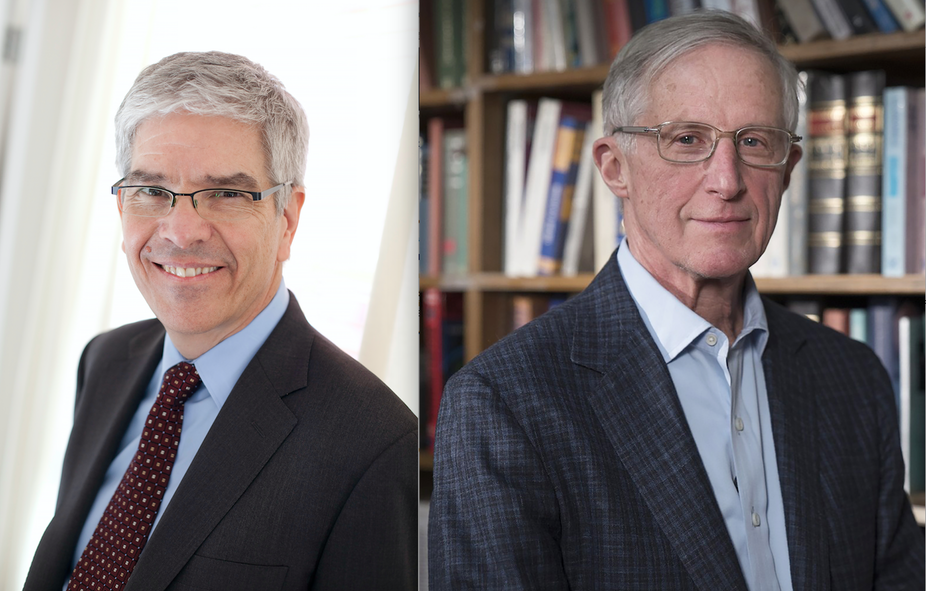

Of the two, it is William Nordhaus’ research which directly addresses the looming horror that is man- made climate change. Since the ‘70s, he has been an outspoken critic of traditional economic models – few of which account for the catastrophic environmental costs that come with increasing productivity. More often than not, building a factory and cleaning a lake after said factory dumps ammonia into it are both labelled ‘productivity’. No distinction is made between the harmful and the good. This is especially true of Gross Domestic Product – the prevailing measure of economic growth. Nordhaus rejected this and proposed an alternative index (charmingly abbreviated as ‘D.I.C.E’) which integrates prevailing climate science, in order to help policy-makers tackle greenhouse warming.

The second winner, Paul Romer, has long been a proponent of technological innovation, arguing that it actually drives economic growth. Luckily, the trend among recent inventions is towards energy efficiency, environmental conservation, and reducing waste. These include such wonders as the KeepCup which you may have seen for sale on the University grounds. Promising to last you no less than three years, as well as save water and energy, it seems like the ideal substitute for a mountain of disposable cups, destined for landfill. Seeing the burgeoning tendency towards these, and metallic water bottles, one might argue that market forces (i.e. student demand for eco-friendly goods) are too volatile for single-use-plastic producers to keep up. But isn’t that the nature of progress?

As a society, we’re more concerned than ever with making sure our actions don’t deplete the Earth’s resources or pollute its atmosphere – even at the cost of ‘traditional’ economic growth. Why then, the endless political clamouring over GDP? Is it because adding another notch to an arbitrary number is considerably easier than tackling the root causes of social hardship? Or maybe politicians are just no good at economics. You be the judge. Suffice to say, we have a lot to learn from both Nordhaus and Romer, who together have laid the groundwork for a science of long-term, sustainable development – though we’d better learn it fast!

Dmitry Fedoseev