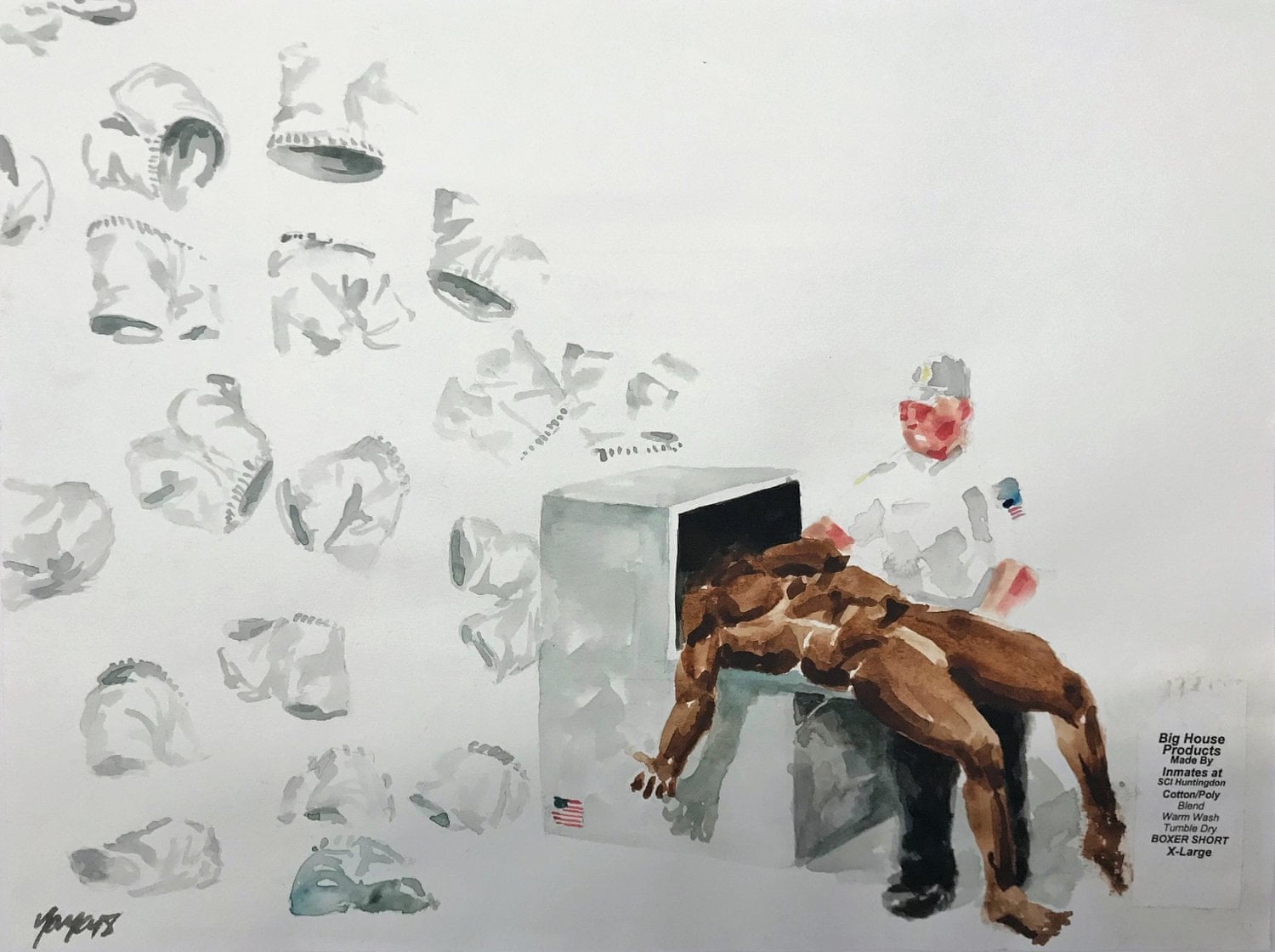

An exhibition entitled Capitalising on Justice has opened at the Urban Justice Center’s exhibition space in Manhattan. Exploring the commodification of incarcerated peoples’ labour, it features artwork made by prisoners for the outside world with a clear cry for help. The U.J.C aims to operate “independently with a common goal of achieving social justice and individual rights…making social advocacy and law reform efforts directly responsive to the daily struggles of those individuals.” The exhibition begins with the following information: “Over the last 40 years, incarceration has grown into an $80 billion industry. One that depends on the human caging of 2.3 million people to extract wealth and resources from the economically distressed, and disproportionately black and brown, communities unjustly targeted by our criminal legal system.” Bianca Tylek, director and founder of the project, wanted “To end the commercialisation of criminal justice and the exploitation of the people in a system that is failing them”.

Companies like Securus and Union Supply charge spouses $3.95 to listen to a voicemail from their partners and a prison labourer gets paid less than 35 cents an hour to make the products that they buy at over tenfold their hourly rate. Extremist capitalism is utilised as a form of punishment, denying prisoners easy access to basic necessities, an ineffective method of “humanising” criminals into becoming more proactive members of society. This exhibition really brings into question what the function of a prison should be; is it to punish? Or should it be to remobilise individuals into a more psychologically sound state where they can function in a life without crime? Ray Dansby, an inmate featured in the exhibition, writes about his ‘Tray of Golden Eggs’, a small sculptural piece depicting hands holding golden eggs. He explains: “The criminal legal system is a goose that lays eggs—each a prisoner, family member, or community adversely affected by the capitalization of justice. Once hatched, they each become a part of the nuclear system, so that even when released they keep coming back.”

In comparison to American prisons, Swedish prisons appear to be taking an opposite agenda; Nils Oberg, 54, director-general of Sweden’s prison and probation service says that “prison is not for punishment… We get people into better shape.” and “Our role is not to punish. The punishment is the prison sentence: they have been deprived of their freedom. The punishment is that they are with us,”. Overall, there is a focus on providing inmates with skills training and mental health support so that they can have another chance to lead better lives. An article published by Global Research in 2008, entitled “The Prison Industry in the United States: Big Business or a New Form of Slavery?” describes how, “for the tycoons who have invested in the prison industry, it has been like finding a pot of gold. They don’t have to worry about strikes or paying unemployment insurance, vacations or comp time. All of their workers are full-time, and never arrive late or are absent because of family problems; moreover, if they don’t like the pay of 25 cents an hour and refuse to work, they are locked up in isolation cells.”. The article goes onto compare the system to Nazi Germany, stating how the imprisoned labour worker dynamic imitates that of a concentration camp, as well as suggesting a huge racial bias in the initial imprisonment of inmates.

John Shine, another artist featured in the exhibition who has served 35 years of his life sentence so far describes how: “Locked away from the public’s eye are the convicted masses society has failed with misdirected funds. They are hidden away and confined in a dark world, a colorless world where, like animals, they are sometimes forced to fight for basic, but seldomly met, mental and physical needs. We should be investing in rehabilitative programs and traditional education informed by applied social science instead of fueling the for-profit prison industry—a booming farce. It’s time for a change.” The majority of prisoners will have to re-enter society at some point, wouldn’t we rather they were more mentally stable after this time rather than making them further psychologically debilitated and more likely to commit further crimes? The artworks in the exhibition are accompanied by highly articulated and insightful captions, not filled with anger but deep emotion and often suggesting conceivable alternative solutions.

This exhibition is no dramatic imagining of distant suffering but real artwork of real prisoners who have in some cases committed horrible crimes, however have an experience of a kind of incarceration injustice we will never know. The exhibition is truly captivating and thought provoking, demonstrating how the prisoners are living under an exploitative, corrupted regime, as they paid slave wages. There is an amazing diverse and disturbing array of art available and if this article has even vaguely interested you do check out the Urban Justice Center’s website to learn more about what they do.

Daisy Elliott

Image Courtesy of James Yaya Hough