The cover-up of workplace harassment by the wealthy was once again brought to the forefront of both parliamentary and public attention last week, with The Telegraph revealing that they had been prevented from sharing information concerning a leading British businessman. Ominously referring to the case as ‘The British #MeToo scandal which cannot be revealed’, they claimed that after months of investigation into allegations of sexual harassment and racial abuse made by staff, the newspaper was blocked from sharing their findings by an injunction against them granted to an anonymous businessman – a man who, like Weinstein, had used controversial non-disclosure agreements involving substantial payouts to silence victims.

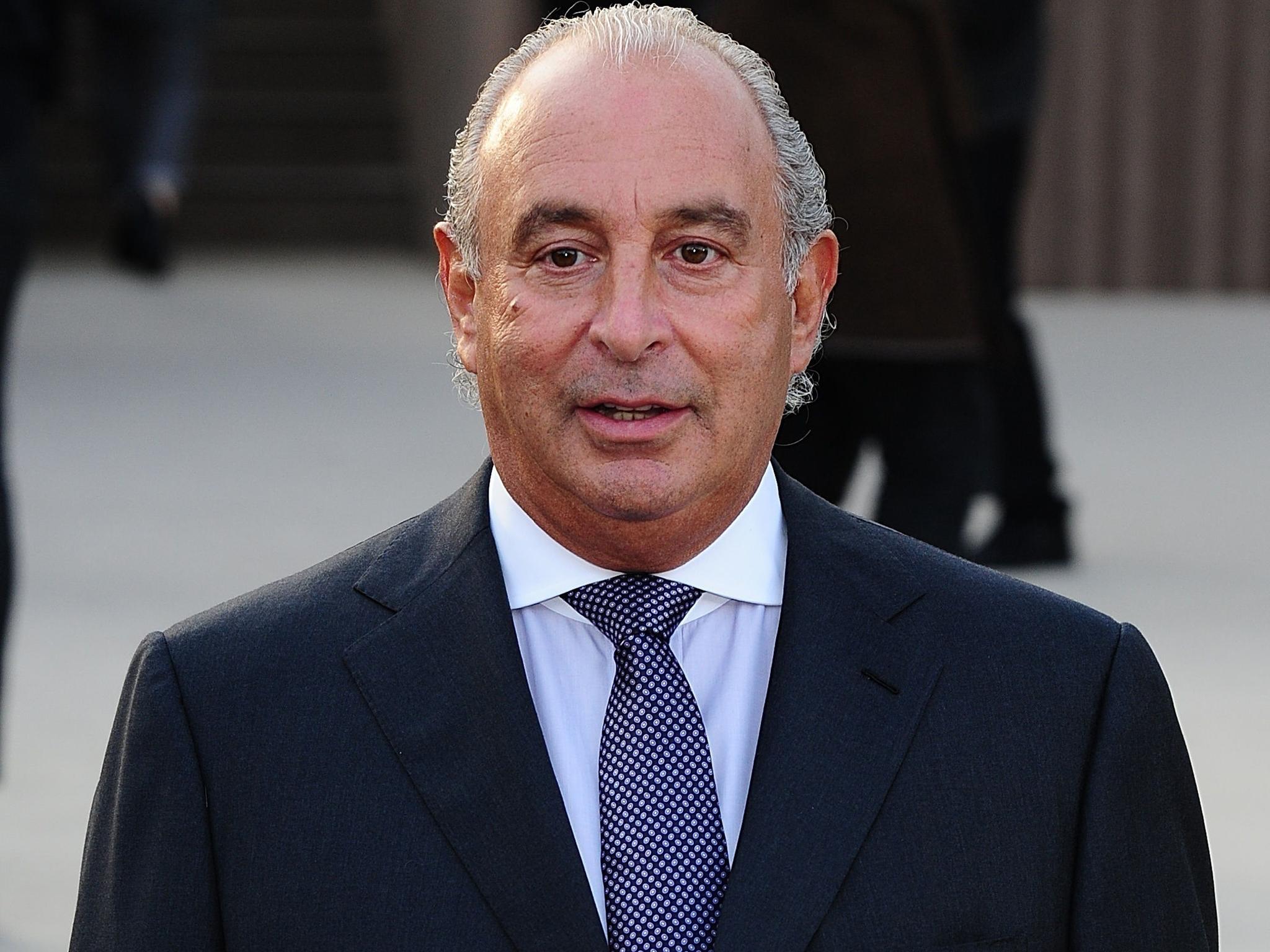

Just two days after the publication of this story, former cabinet minister and life peer Lord Peter Hain used parliamentary privilege – an ancient right that grants certain legal immunities to members of both the House of Commons and House of Lords that allows for free speech without fear of defamation or libel charges – to name Sir Philip Green, chairman of the Arcadia group that owns chains such as Topshop, as the man involved.

Since this disclosure, the ethics of Hain’s overrule of appeal court judges has been fiercely debated, with critics expressing concerns over potential harm to the case and the claimants involved. Defending his decision, Hain described the reveal as the right course of action due to the case being ‘clearly in the public interest’, and because of the concerning influence wealth could potentially have on the case.

To me, however, the burning ethical question is not whether his decision to name Sir Philip Green was right or wrong, but is instead whether an unelected figure such as Peter Hains should have greater power to decide what course of action is right than our legal system. In 2015, Hain was nominated for and accepted a life peerage – a position in the House of Lords appointed by the monarch under the advice of the Prime Minister – despite previously saying he supported a fully elected second chamber.

As a prominent Labour MP and noted anti-apartheid campaigner, I am not denying that Hain’s commitment to politics and social justice both in the UK and worldwide is impressive, but I struggle to agree that within a democracy the past actions and achievements of any individual should entitle them to a lifetime of the kind of power this reveal demonstrates. Of course, the involvement of such immense wealth in the case of workplace harassment is concerning; we have seen money and influence used as a means of avoiding accountability often enough to be aware of that. There is no doubt that, with the abuse of NDAs and the legislation surrounding their use set to be debated and reformed by Parliament, the general public deserves access to the information required to foster informed democratic debate. However, this does not change the fact that the decision to disclose this information was made not by an elected representative, but by an individual granted power through a system that is fundamentally outdated and in dire need of reform.

In a letter appearing in the Guardian this summer, Chief Executive of the Electoral Reform Society Darren Hughes revealed that the House of Lords is (perhaps unsurprisingly) largely dominated by ex-politicians and peers living in and around London, with the North and Midlands remaining under-represented. There was just one peer whose main background was classed as manual or skilled work. Thus for many, Peter Hain’s decision will remain bittersweet. On the one hand, this is a commendable case of someone in a position of power empathizing with and standing up for those who do not have a voice. It sends a message to individuals like Philip Green, (who has spent an estimated £500,000 on legal fees to protect the identities of himself and his company) that there are those who will not allow money to guarantee protection from accountability.

However, I will always struggle to celebrate an act that so blatantly highlights the abilities of an unelected few to lawfully undermine our representatives and our legal system within the constitution of UK Government.

Connie Lawfull

(Image Credit: The Independent)