With the Marvel film Venom hitting the cinemas on 5th October, now seems the perfect time to get the message out about just how much of a neglected danger venom is in the real world. What I mean by venom here is not the symbiotic alien in the film, but the toxin which is injected into the body through means of fangs, stingers and sometimes spurs. All manner of animals are venomous, from Komodo dragons to the adorable slow loris. Venom is mostly used for taking down prey, but can be used for defence if the animal feels threatened.

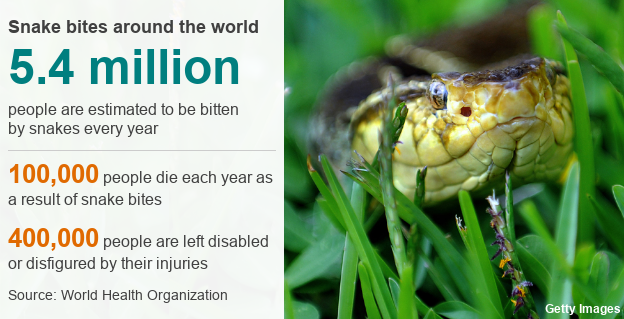

This can be a huge issue when humans come into contact with snakes as their camouflage makes them difficult to spot and some of the most venomous ones, like the Russell’s Viper, commonly occur near built up areas.

This can be a huge issue when humans come into contact with snakes as their camouflage makes them difficult to spot and some of the most venomous ones, like the Russell’s Viper, commonly occur near built up areas. You can imagine that this leads to many snakebites from accidental close contact with the snakes, which is a huge issue in tropical developing countries. In the UK, however, the worst snakebite we can get is from the adder, a species of viper which, although still venomous, is unlikely to kill you due to our excellent medical response to bites. In fact, the last death from snakebite in the UK was in 1975.

In fact, the last death from snakebites in the UK was in 1975.

This is in stark contrast to the state of affairs in developing countries where snakebite envenomation is listed by the WHO as a neglected tropical disease. Imagine you are in a rural Indian area, where most snakebite deaths occur, and you accidentally step on and get bitten by a venomous snake. In rural areas, even if you have a phone and signal, help is unlikely to get to you quickly due to lack of infrastructure. Identifying the snake that bit you is difficult but essential for the antivenom treatment. For a Russell’s viper, bleeding from the mouth can occur within 20 minutes, though many people faint within the first 5. It is not uncommon for 30 vials of antivenom to be needed in order to survive a bite from this viper, but in developing countries access can be difficult. Antivenoms lose their potency quickly and so the logistical challenge of supplying all the medical centres with antivenom is usually too great for most rural areas to be effectively equipped. Recovery from Russell’s Viper bites is rare as they cause acute renal failure, leading to thousands of deaths per year.

It is not uncommon for 30 vials of antivenom to be needed in order to survive a bite from this viper, but in developing countries access can be difficult.

This may seem bleak but a charity called the Global Snakebite Initiative is working to overcome these issues. They aim to help provide low-cost and robust antivenoms in a world where the standards of these cure has fallen well below that of other therapeutic agents. Further research is also being conducted across the world into ways that snakebites can be avoided and possible artificial antivenoms which don’t require the use of an animal, usually a horse, to produce the antibodies used in the antivenom. If you are interested to learn more, there is a Venom Day held at Bangor University on Saturday December 8th which has speakers on a wide variety of subjects which is definitely worth a visit. If you like to come, you can find more information on their Facebook event by clicking here.

Donate to the cause: https://www.snakebiteinitiative.org/?page_id=791

Komodo Dragon: As a child, I remember being told that the Komodo Dragon’s saliva contained potentially lethal bacteria and that this was how it brought down the big prey, like water buffalo, it sometimes pursues. This made sense to me watching the strings of saliva roll down the huge lizard’s dirty mouth on TV but the idea has been overturned. It turns out that the lizard actually produces a slow-working venom, making it the largest living venomous animal. There are recent suggestions that among extinct animals this title could have gone to the mosasaurs, the 15m aquatic reptiles made famous in the film Jurassic World.

Slow Loris: These are the only venomous primates known to science and the way they inject their venom is quite intriguing. In snakes, the venom gland is held within the mouth and the venom is injected down hollow teeth. Conversely, in the slow loris the venom glands are, in fact, on their arms. When threatened, the slow loris will hide its head under its arms and lick the glands, mixing the venom with saliva. A bite after this adorable display could prove fatal to humans but only if you have an allergic reaction to the toxin. A video of a pet slow loris went viral a few years ago and this severely damaged the species’ wild population. Hopefully, if prospective owners’ moral compass doesn’t deter them from illegally buying a pet loris, the threat of a venomous bite will.

Slow Loris: These are the only venomous primates known to science and the way they inject their venom is quite intriguing. In snakes, the venom gland is held within the mouth and the venom is injected down hollow teeth. Conversely, in the slow loris the venom glands are, in fact, on their arms. When threatened, the slow loris will hide its head under its arms and lick the glands, mixing the venom with saliva. A bite after this adorable display could prove fatal to humans but only if you have an allergic reaction to the toxin. A video of a pet slow loris went viral a few years ago and this severely damaged the species’ wild population. Hopefully, if prospective owners’ moral compass doesn’t deter them from illegally buying a pet loris, the threat of a venomous bite will.

Russel’s Viper: Although this animal is responsible for a great number of deaths each year, that does not mean it is acceptable to demonise them. Despite what some news sites would have you believe, snakes do not “attack” humans, if anything it is quite the opposite: from the snake’s point of view, the human is the potential attacker. Many times their size and potentially standing on their tail, humans are a scary thing for a snake to encounter, no wonder they use their most effective weapon against us! Even then, many snakes will do “bluff bites” where they strike with a closed mouth, or dry bite where no venom is injected. This is what makes Russell’s viper so dangerous as they seldom deliver dry bites and instead inject as much as they can meaning that the victim is left with a huge amount of toxin in their system.

Russel’s Viper: Although this animal is responsible for a great number of deaths each year, that does not mean it is acceptable to demonise them. Despite what some news sites would have you believe, snakes do not “attack” humans, if anything it is quite the opposite: from the snake’s point of view, the human is the potential attacker. Many times their size and potentially standing on their tail, humans are a scary thing for a snake to encounter, no wonder they use their most effective weapon against us! Even then, many snakes will do “bluff bites” where they strike with a closed mouth, or dry bite where no venom is injected. This is what makes Russell’s viper so dangerous as they seldom deliver dry bites and instead inject as much as they can meaning that the victim is left with a huge amount of toxin in their system.

Image source Russel’s Viper: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russell%27s_viper#/media/File:Tushar_mone.jpg

Image source Komodo Dragon: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komodo_dragon#/media/File:Komodo_dragon_with_tongue.jpg

Image Source Slow Loris: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/02/04/national/crime-legal/endangered-slow-lorises-illegally-sold-japan-study-suggests/#.W8nljmRKj5Y

Image Source WHO: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-44253586