Giulia Pesce reflects on Kendrick Lamar‘s involvement with Black Lives Matter, the political message behind hip-hop and why we should all still be listening to Lamar‘s seminal record, To Pimp a Butterfly, three years on.

When I talk to my mum about rappers, she probably has a clear image in her head: huge tattoos, diamond chains, money, joints, you name it. She certainly wouldn’t expect a Pulitzer prize winner. But Kendrick Lamar is quite different from the stereotypical image associated with rappers of his generation, and here’s why.

Born in Compton, California, Lamar is a famously conscious rapper. His art revolves around the analysis of American social behaviour, politics and his resistance against institutional, often violent, racism. Over the years, he has proved to be socially conscious and active, and his music has had an impact on one social movement in particular: Black Lives Matter. Lamar, in these times of social uncertainty, represents more than ever the voice of the voiceless. His music has taken hold to inspire and support issues of race, gender and age; it unifies when society fails to.

Since rap can often be recognised as a demonstration of social malaise and racial struggle, when an movement like Black Lives Matter burst onto the scene, many rappers wished to give more visibility to the cause and spread the word. BLM echoes the old Universal Zulu Nation, an organization founded by hip hop pioneer Afrika Bambaata in the 70s. It shares the same values and ideals: love, unity, and peace.

Kendrick Lamar is undoubtedly one of the most influential rappers to join the cause, especially when considering his infamous Grammy-winning record, To Pimp a Butterfly. Lamar’s third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly was released on March 15, 2015. The title, in an ode to Tupac Shakur, recalls the personal journey of the artist in his metaphorical transition from caterpillar to butterfly. The attempt to break free from the influence and institutionalization of American capitalism and prejudice are personified in the tracks under the respective figures of Uncle Sam and Lucy (short for Lucifer).

Despite this record being released over three years ago, the issues of race raised by Lamar still deeply resonate with current political discussions of today. The close link between music and politics has been explored by so many artists, through different kinds of mediums, and hip-hop is no exception. Born during the financial crisis of New York at the end of the 1970s, hip-hop has always stood out for its rough and raw exploration of harsh realities. At its very core, hip-hop expressed the discontent of the Black community, and even if times have changed, the Black malaise has not. To Pimp a Butterfly is a rich album that reflects not only this struggle, but also Lamar’s views on the music industry, capitalization and human viciousness.

It is only halfway through this masterpiece that we find the song that matters the most in relation to Black Lives Matter: ‘Alright’. This song has become the unofficial hymn of the movement, and from the first listen, it is clear why. Lamar is not the kind of artist who exposes himself much in interviews, so he never directly confirmed the motives behind the track at the time he was composing this album. However, if actions speak louder than words, and the lyrics are not enough to prove his concern and critique of the state of gun violence in the US, the music video for ‘Alright’ and his performance at the 2015 BET awards paint a more explicit picture. “Alls my life I has to fight, nigga” he sings in the first verse. In a mere nine syllables, Lamar summarized the intense struggle of not only his generation, but the many generations which came before him. Listening to this song, it is not hard to understand the reason why it has become the anthem of such a vital social movement.

It all started at the end of July 2015, in Cleveland – the city designated with hosting the Movement for Black Lives National Convening. After three days, the Convening ended, with a view to unite any institution interested in continuing the fight in favor of Black identity and equality. On the last day, a fourteen-year-old Black teenager drew the attention of a Cleveland Regional Transit Authority officer, who saw him on a bus and thought he was intoxicated to the degree that he would not be able to take care of himself. The officer intended to send him to detention, but the gathering protesters surrounded the scene, to prevent the officer from leaving with the boy. The crowd started singing ‘Alright’, a chant of hope and faith.

This song reflects a determination to never cease in the fight against social injustices. The hook of the song incessantly repeats “we gon’ be alright”, a mantra which is as concise as it is defiant. Like a figure of prophetic encouragement, Lamar and his anthem act as a reminder to anyone who is losing hope and who needs a spur: do not lose faith, we are gonna be fine, we gon’ be alright.

The song continues: “When you know, we been hurt, been down before, nigga / When our pride was low, lookin’ at the world like, ‘where do we go, nigga?’/ And we hate Popo, wanna kill us dead in the street for sure, nigga.” In this verse, the anthem proves to be inspired by Lamar’s concerns over police brutality. Recognising that the Black community has been hurt before, Lamar traces the roots of structural racism from contemporary issues of police brutality to the moment African slaves vainly looked around the new and vast land they had been forcibly removed to. The rapper also refers to the general distrust of the police due to their often unjustified violence towards Black communities and individuals.

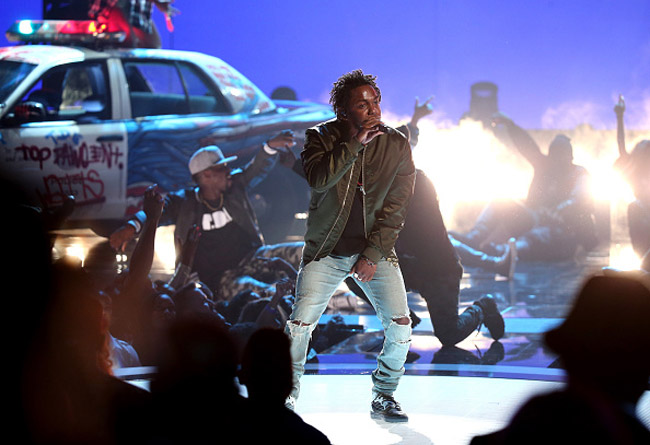

This specific verse, however, has not been well received by the media. In fact, Lamar excluded it from his performance at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards, a decision which has led many to believe that he was forced to make the cut. The theory makes sense; Lamar was heavily criticised for his previous performance of ‘Alright’ at the 2015 BET awards, where, he sang the inflammatory critique of the police on top of a cop car, covered in graffiti, with a ripped American flag in the background. American talk show host, Geraldo Rivera, attacked Lamar and his performance, saying it was, “to say the least, not helpful at all. This is why I say that hip-hop has done more damage to young African Americans than racism in recent years.”

According to Rivera, the open discussion of contentious topics like police brutality merely serves to add fuel to the flame of discontent, rather than quelling it. Instead of attacking the source, Rivera attacks the which the source has created. Rivera also assumes that Lamar’s message is one of hatred, and that he meant to promote violence against the police.

The Compton rapper fired back two years later, when he sampled Rivera’s words in the track ‘DNA.’ from the critically-acclaimed DAMN. Speaking on the subject in an interview, Lamar argued that Rivera twisted his words: “Hip hop is not the problem, our reality is the problem.” In the interview, Lamar was disappointed but unsurprised by the way the media misunderstood his words, seeing it as yet another extension of the issues he fights against. After all, it must be hard for white-middle class men like Rivera to identify with a reality they have never and will never experience firsthand.

The more one listens to hip-hop, the more it is evident that the context these artists were born in defined their lives and artistic path. In the end, ‘Alright’ should be considered not only as a spur-of-the-moment form of art, but also as an enduring social warning. As much as Lamar wishes and hopes for the racial bias to dissolve, he also knows that racial discrimination is deeply-rooted in American society.

Kendrick Lamar told the story of Blackness as a strength through To Pimp a Butterfly, marking himself as a spokesperson for the voiceless in the process. To Pimp a Butterfly is overwhelming and remarkable, from the first to the last track. It catches Lamar as he questions his identity, first as a rapper, and then as a Black man. And mostly, in a world where numbers count more than the message, it shows a man’s realisation of the fact that the society he lives in actively encourages divergences within Black communities in order to weaken their empowerment and prevent their unity. But Lamar, through all his resistance, uses his music as a means of unity, to spread love and awareness. After all, that is what hip-hop was born for.

Giulia Pesce

Header Credit: Rap-Up