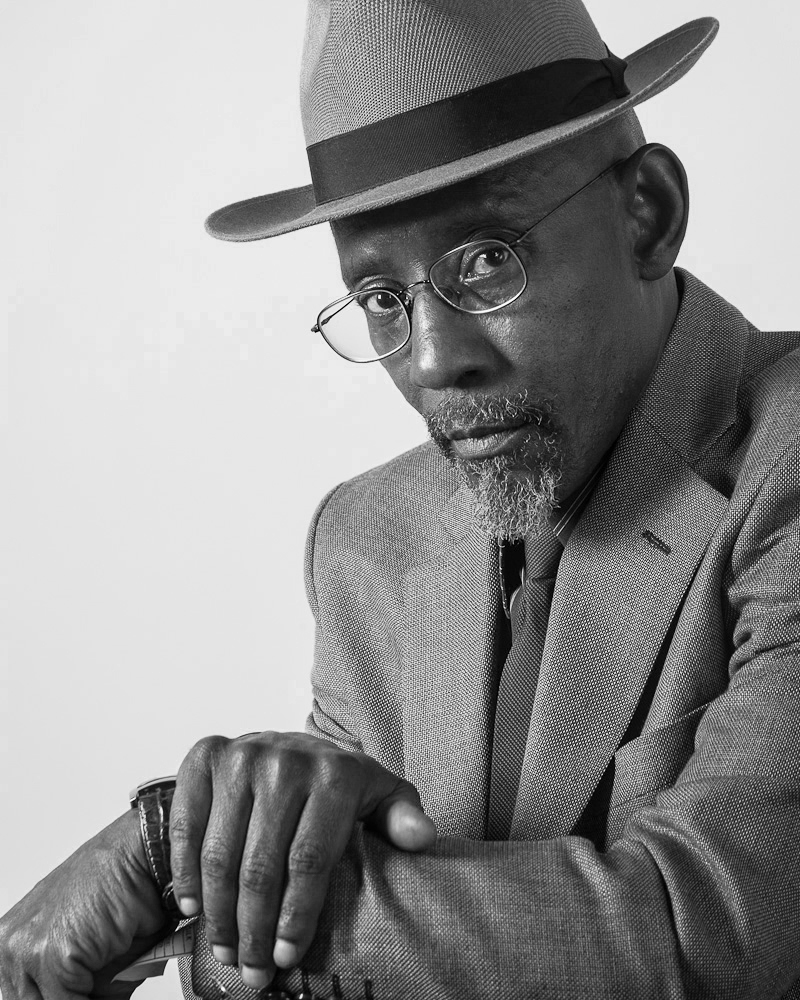

Jodie Yates could write a book about Linton Kwesi Johnson, the Black British poet renowned for his pioneering form of dub-poetry. But you can check out the abridged version of his life in this week‘s blog.

For me, Black History Month brings with it many names, faces and stories that have inspired the mobilisation of Black people around the globe. But of all the available faces, this particular month, I’m dedicating my spare time to spreading the wisdom of Linton Kwesi Johnson. Poet, activist, musician, educator, Jamaican, Black British – Linton Kwesi Johnson’s biography is vast and unlimited. Known as the British forefather of dub-poetry, LKJ is a figure that has revolutionised every form he takes on.

Born in Chapelton, Jamaica in 1952, Johnson moved to a hostile and unwelcoming London aged 11. From that point onwards, the myth of London that was sold to then-colonies was one that Johnson’s work aimed to dismantle. Attacking the institutions and figures that enforced systematic racism upon Britain’s ethnic minorities, in a time of rife violence, Johnson’s only weapon was cultural: poetry. From protest, to 12”, to seminar rooms, LKJ’s poetry has been instrumental in mobilising the struggle for equality for Black Britons, as it transcends form and audience.

Hyperconscious of his time and environment, Johnson’s poetry is a dedication to the presence of the ethnic minority communities in Britain and around the world. ‘Reggae fi May Ayim’, ‘Reggae fi Radni’ and ‘Reggae fi Peach’ are eulogies to revolutionaries and activists, whilst ‘Di Great Insohreckshan’ and ‘New Crass Massakah’ illuminate events that were pivotal for the Black community in Britain – the Brixton Riots and the New Cross fire of 1981. These events and characters were painted by a racist media as criminal. But the jovial reggae beats and lyricism of Johnson‘s dub poetry rewrote these narratives, honoring activists and celebrating revolution.

‘Reggae fi May Ayim’

Wi give tanks

Fi di life

Yu share wid wi

Wi give tanks

Fi di lite

Yu shine pon wi

Wi give tanks

Fi di love

Yu showah pon wi

Wi give tanks

Fi yu memahri

Linton Kwesi-Johnson

The gravity of the subject matter of Johnson’s poetry – racism, murder, police brutality – is contrasted against the style of the accompanying music, a reminder that music is a form of empowerment against the oppression that permeates life for people of colour. This sonic page to sound contradiction is embodied by the relationship between Johnson and his longstanding collaborator, reggae pioneer Dennis Bovell. Bovell’s stage presence is exuberant and boisterous, an image of liberation, yet Johnson’s seemingly stern persona is the lyrical anchor that reminds his audience of an ongoing struggle.

British society is in a state of regression, heading towards the oppressive and stifling racism Johnson has been fighting against for the past forty years. Politicians hark back to the need for stop and search laws, but in doing so reveal the same racist rhetoric that Black people are suspect and criminals – after all, Black people are eight times more likely to be stopped by British police.

Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poetry is an insight into the lives of those who are oppressed and a reminder that we still occupy a system which operates on the legacies of colonialism. Brexit and the Windrush scandal are a pressing reminder of this. This Black History Month, looking back on the historic oppression of Black people should illuminate its resonance in contemporary society. When Black people are being unfairly deported, imprisoned and murdered, now is the perfect time to ask if we are doing enough.

Johnson’s revolutionary dub poetry is ever-relevant, a call to mobilise the Black community, and celebrate the power of their presence in a world which is systematically anti-Black.

Jodie Yates

Image: Speaking Volumes