The Only Story is Julian Barnes’ latest novel, published just over a month ago. People swoon over his books, particularly Flaubert’s Parrot (1984) and The Sense of an Ending (2011). I had never read a novel of his before, and had some mild preconceptions.

I found the book madly compelling. With just 200 pages, I read the first three-quarters in an afternoon. Horribly daunted as the plot became more dismal, the last 50 or so pages were eked out agonisingly over two days; there wasn’t great mystery as to how the story must end, but my frugality felt apt due to the softening of narrative momentum.

The story is Paul’s, told retrospectively from old-ish age. Though the scope of years is broad, the narrative is wonderfully structured, so the stretch of time doesn’t overwhelm or feel thinned in its hugeness. The book has three parts, the first of which is a first-person narrative from the then-19-year-old (Part II is in second-person narrative, and Part III is told in third.). During a university holiday, Paul joins the tennis club in his village to occupy himself, which is in a suitably depressing slice of London commuter territory. There he becomes enamoured with Susan, a married 48-year-old fellow tennis-player. Their relationship is complicated, though Paul’s plotting of the relationship feels interestingly deliberate and considered. His narration is fascinatingly self-aware and diligent, though Paul is both emotionally and factually truthful. It feels so sobering to absorb the mess of a relationship written in this way; the book felt cleverer and cleverer the more I reflected on it, while the experience of reading it remained somehow undiluted by my own analysis – Paul’s self-awareness, perhaps, being enough for the both of us.

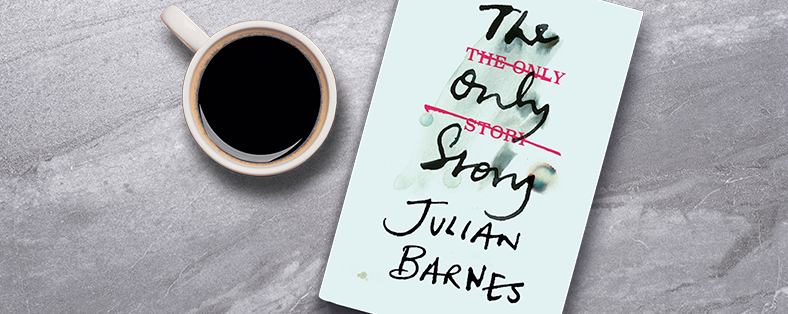

The Only Story by Julian Barnes is published by Jonathan Cape (£16.99).

Charlotte Vyvyan

Image: Penguin Books