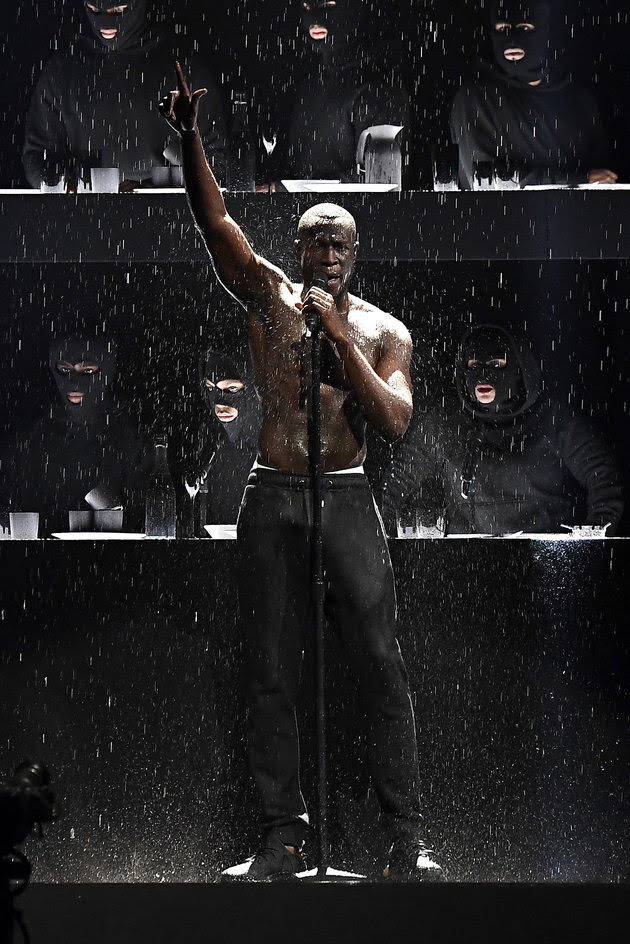

The Brit Awards 2018 provided yet another yearly dose of lacklustre ‘banter’, gentrified drab and predictable winners for this year’s cosy creations. The one uplifting moment which stood out above the vapid, however, was Stormzy’s crowning of Best British Male Solo Artist, accompanied with the British Album of the Year for Gang Sings & Prayer. After winning his two awards, Stormzy took to the stage with a sudden flash of enlightenment, unfurling a venomous tirade against Theresa May which pushed the question, “Where’s that money for Grenfell?”.

The reaction to Stormzy’s passionate performance has been rather split. Whilst many people have applauded the Best British Male Solo Artist for using his pedestal to challenge the government’s negligence, many, such as Tory MP Philip Davies, have dismissed him completely.

Whilst appearing on News Thing, Davies shunned Stormzy’s opinion, suggesting that his profession means he ought to focus simply on his music, whilst any form of political issue should be left to the matters of somebody else. Furthermore, Davies’s repressive argument appears to reject Stormzy’s rap for its specific political leanings: “It’s all these sort of left wing artists playing to the gallery […] trying to be trendy and being pro-Corbyn”. Ah, we seem to have reached the crux of the criticism. If we were to spin Stormzy’s rap on its head, however, so that it praised the Conservative government, would we expect the same amount of criticism from the political elite? I’ll take a punt: of course not.

This dismissal of political discourse in music is obviously nothing new and for decades there has seemingly been an attempt to wipe music of its social value. John Street’s book, Rebel Rock: The Politics of Popular Music, provides a great insight into the ways in which political and progressive views may be squandered within the music industry:

“In signing performers, a company tends to act conservatively. Its natural inclination is to ensure a constant supply of recognizably similar musicians and music, appealing to the same kind of audience and sold in much the same kind of way. Anything that disrupts this pattern is relatively costly.” (p. 102)

It would appear that the business of many major record labels is to produce music that poses no political challenge and thus keeps to the tastes of mass consumers; music’s political impetus is thus eradicated in favour of maintaining the status quo. Whilst this does not mean that political discourse is excluded completely from the realm of mainstream music, as Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar have recently demonstrated, it does suggest that there is a floor of egg shells which many are uncomfortable in treading on.

But can music really be so far-removed from politics? At this point, I must ponder on the etymology of the dreaded p-word: amongst its origins is the Greek word politikos, meaning “of, for, or relating to citizens”. If politics is to be defined as the representation of the people, how can we expect it to be so distant from the most popular forms of expression amongst the people?

In his talk, ‘Defending Music’s Social Value: Fighting the Systematic Muting of Our Most Powerful Artform’, Rou Reynolds, frontman of the outspoken band Enter Shikari, expresses the value which music has served within society since its existence. From 15:45 in, Reynolds explains that all art, regardless of its intention, encourages or endorses some form of politics. as Reynolds states, whilst some music makes use of its social value through meaningful discourse, other music betrays it in its banality; the rejection of its political impetus and social value thus results in “socially-unconscious music”.

All art, as a means of people expressing themselves, has the power to be political: the murals you see in the streets; the books you read; the music you listen to. The problem is not that politics has no place in music, it is that the political elite are scared of music’s place in politics. It is no surprise, therefore, that Philip Davies wants to dismiss the views of a group of musicians that overwhelmingly came to the support of the Labour Party in the 2017 Snap Election, most obvious in the #Grime4Corbyn campaign. The Conservative government are scared of music’s political strength because they know that its connection to youth culture does not favour them. The political elite are quivering; music is no longer dithering.

Kieran Blyth

Photo Credit: Huffington Post