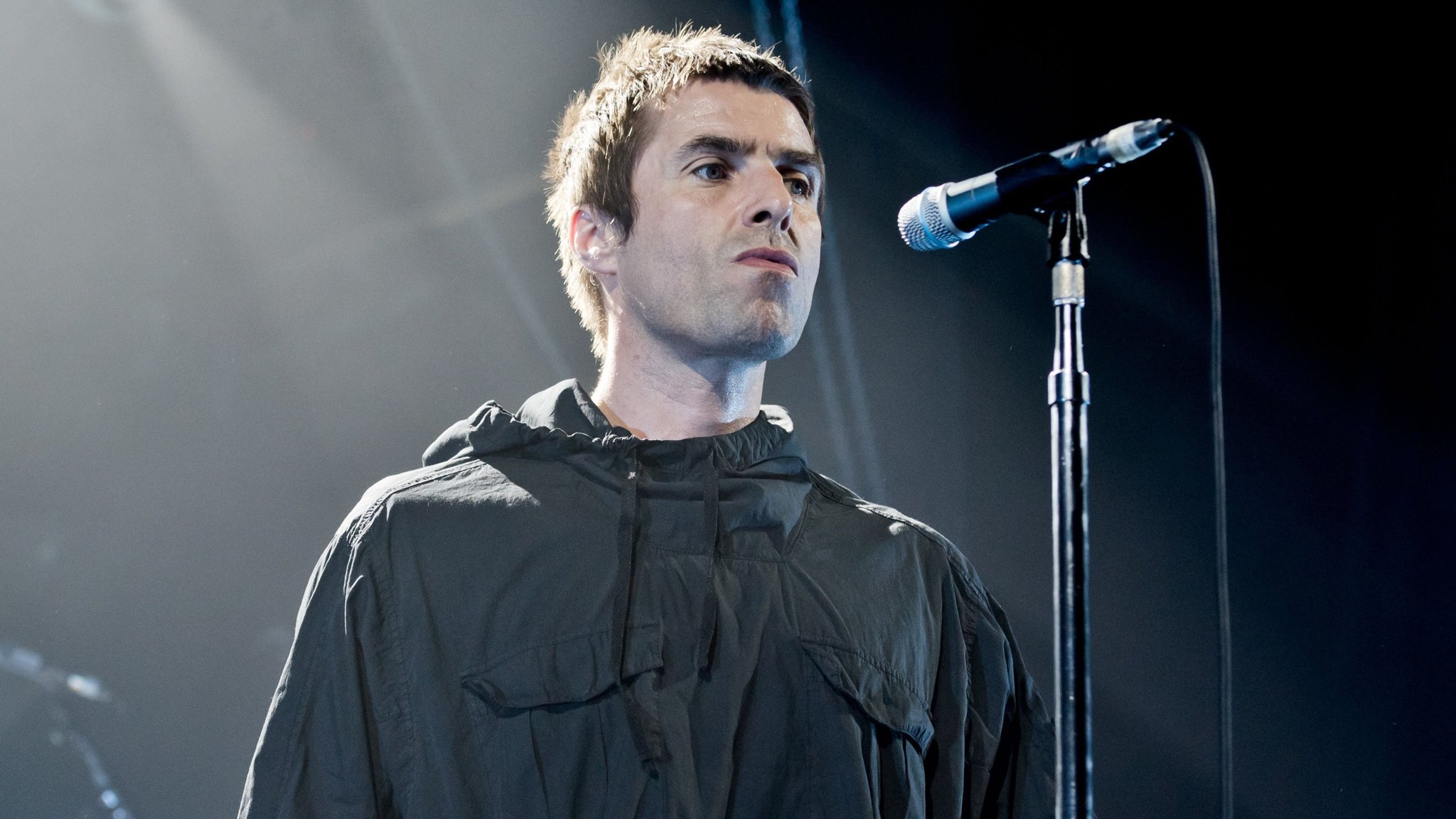

Are women welcome in the masculine sphere of Britpop? Digital Associate, Juliette Rowsell, discusses her experience at a Liam Gallagher concert that turned into a display of lad culture at its grittiest.

When you think of Liam Gallagher, what do you think of? Cigarettes and alcohol? The epitome of the 90’s rock n’ roll star? Excessive swearing? Avid football fan? Something that underpins these ideas, is the image of excessive lad culture.

As a Christmas present, my mum bought us tickets to see Liam Gallagher at the Barclaycard Arena in Birmingham. Oasis were the band that got me into music, and my inner fangirl was reignited.

However, from the outset of the gig, I had an inkling that something wasn’t right. But, if I were to have talked about the issues at the time, I would have been deemed to be over-reacting. For a woman to speak out about male behaviour in such environments is to risk being dubbed a ‘feminazi’ and overly ‘P.C.’. Yet, this in and of itself is internalised sexism: as women, we are taught to accept and internalise blame. It must be us that there is an issue with, rather than the behaviour of men that makes us feel uncomfortable.

Britpop revolved around the superior image of the god-like rock star and their adorning fans. This was a gendered division, and an A-List model girlfriend became the indicator of a successful career and cemented the rock star image. The working-class lad in adidas trainers turned coke-snorting, above the law rebel was the hero of Britpop. With this came a sense of rock n’ roll arrogance and inflated sense of self belief. Britpop was as much an attitude of male rebelliousness against middle class sensibilities as it was about music.

Thus, when support band Rat Boy, a four piece “white-boy” indie band meandered on stage, guitars and beers in hand, battered vans on, floppy hair perfectly in place, they conformed to every trope associated with this image.

“Britpop was as much an attitude of male rebelliousness against middle class sensibilities as it was about music.”

But this isn’t 1997. In 2018, when four white men walk on stage with mediocre throw away indie that feels eight years too late to the party, this arrogance no longer sits well. While many indie bands that first emerged in the early 2010s have moved on to include subtle elements of pop, funk and even RnB to push the genre beyond its tired formula, Rat Boy are stuck in this throw away guitar ridden indie that has lost its punch. So what is it that has carried them through that has allowed them to support Liam Gallagher? Part of what seems to have propelled them forward is their embodiment of this rock n’ roll star, ‘lad of the town’ image – an image and arrogance that does not carry female bands of the same ilk through.

What followed was a scene that is familiar to all gig goers: it was the break between the support and main act, music was blaring out of the speakers, and the crowd was getting lairy. As indie classic after indie classic came on, the crowd became increasingly intoxicated with this legacy of music. But when we talk about ‘indie classics’ we have to question what this means.

“How, as a feminist, am I meant to feel comfortable when “I am the Resurrection” comes on, four condoms are being thrown around the crowd, and guys are taking their shirts off then swinging them around as beer is being thrown like confetti? When every man in the room feels validated in a joint sense of lad culture by a cannon of music, culture and heroes that celebrate such behaviour?”

Throughout the interval, not a single song by a female artist played over the tannoy. Think about all the bands we idolised as indie kids growing up in the early 2010s: The Smiths, The Cure, Joy Division, Oasis, Blur, The Libertines, Arctic Monkeys. What do they all have in common? They’re all white men. When the final song came on – ‘I am the Resurrection’ by The Stone Roses – an almost exclusively male mosh pit emerged in the crowd; almost all of them were shirtless, beer was thrown like confetti, four condoms were flying over their heads. Do I spend money on a gig just to be forced up against a guy’s sweaty back? Surprisingly, I do not. As they screamed ‘your face it has no place’ and ‘I am the resurrection’ along with Ian Brown, what was being celebrated was a cannon of music that prides itself on its belief in its own self-importance. Suddenly, this song was transformed from indie banger to a song that represented the euphoric freedom of being a ‘lad’. And this seems to be a surprisingly common theme of many Britpop songs: this sense of invincibility.

My mum and I were sat in the seated area. As Liam came on, the two men sat in front of me instantly stood up, arms wide. In a moment of self-awareness, one of them turned around and asked us and the two women by us if we could see when he stood up. We all said no. He put his hands together and begged us to stand up. When we said no again, he shrugged his shoulders, and carried on.

In this came the assumption that he could do what he wanted despite the complaints of others. It came with the assumption that his incredibly extroverted and bodily way of gigging was the ‘correct’ way of enjoying music, and that other ways of gigging (i.e., sitting in the seated area) are invalid forms of musical enjoyment, and that his superior way of gigging was allowed to take precedent over how we decided to enjoy ourselves. In begging us to stand and us choosing not to, he also placed the blame of our issues on us by insinuating that it was our fault for not conforming to his way of enjoyment. Needless to say, we got no apology.

Throughout the night, there was one female musician on stage: the cellist. But, in having this token female, it seemed to reinforce the idea that rock is for men; women can partake in ‘gentle’ and ‘unexciting’ forms of music, but the almighty and superior rock n’ roll, is for men. Sorry girls, didn’t you know that women can’t play guitar?

Masculinity within Britpop/indie culture is so normalised that it has a sense of untouchability. It is rarely questioned that its history is highly problematic and exclusionary. Yet, it’s not necessarily Liam Gallagher himself who is at blame here. It’s what he represents to the thousands of men who adore him that is the issue.

Liam Gallagher represents ‘the dream’: the dream of rock n’ roll success, this attitude of pure invincibility laid on a solid foundation of sex, drugs and rock n’ roll. He represents the image of ultimate ladhood that is under threat in 2018 from P.C. politics and liberal attitudes.

So, where do I stand as a 5”3 female who does not conform to these masculine expectations in a genre like Britpop? Answer: I don’t. There’s something quite feminist about being a woman and screaming ‘Rock n’ Roll Star’ into your hairbrush in your bedroom. But as soon as this is taken outside of the private sphere and you’re in a room of lairy men who have every aspect of their masculine entitlement validated by a cannon of music, lyrics and heroes, it no longer feels empowering.

I left a night I was so excited for feeling deflated and othered; this was not a gig for all, but one for the boys. As The Stone Roses sang, here in this gig that validated every male ego in the room, I realised, my female face, it had no place in a gig which was a celebration of male privilege.

Juliette Rowsell