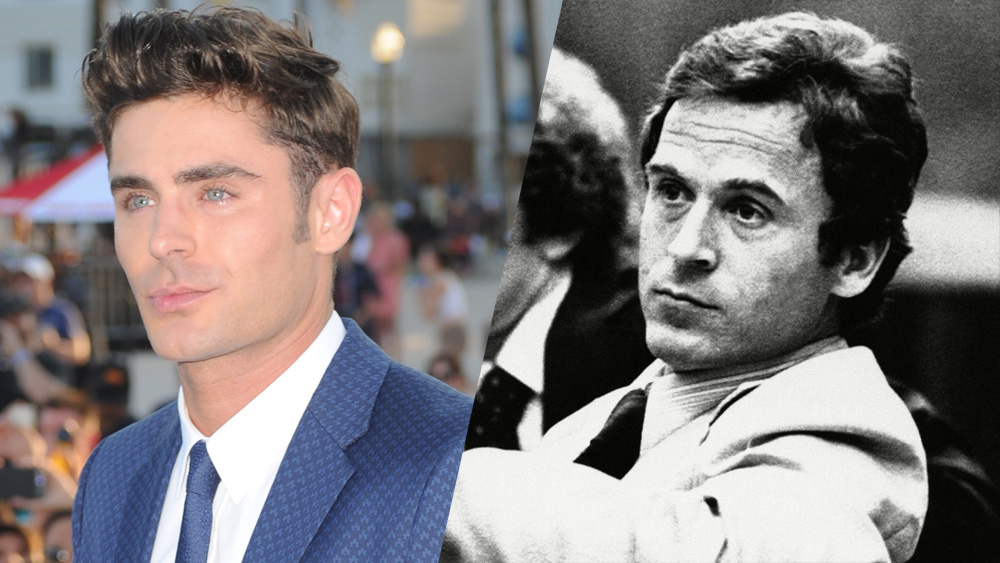

Arts Editor, Rose Crees, discusses whether Zac Efron portraying Ted Bundy is potentially problematic.

2017 was a year of unprecedented bizarreness. Its twelve months included events such as: Kendall Jenner attempting to initiate world peace through the sheer power of Pepsi, the Babadook’s much celebrated coming out (thank you Netflix) and whatever ‘covfefe’ is, there was hope that 2018 would become a year of relative normality. Yet when January came around so too did the news that Zac Efron has been cast to play Ted Bundy in Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, a biopic about the serial killer’s life, once again seeing the expected completely and utterly subverted in mass media.

The role requires Efron to embody the serial killer, kidnapper, rapist, burglar and necrophile whose victims were countless young women and girls. Operating mainly in the 1970s, Bundy confessed to 30 murders across seven states, yet it is widely assumed that his victim count was much higher. While a far cry from the actor’s usual roles playing facets of Zac Efron as Troy Bolton (High School Musical), Mike O’Donnell (17 Again) and Phillip Carlyle (The Greatest Showman), Efron’s striking image and charisma may prove handy for the role. Bundy was known for luring his victims with his charm, looks and fake plaster casts of fictional injuries for which he would request their help but it is still difficult to imagine the Disney Channel protégée who grew up alongside many of his viewers sinking to the psychopathic yet magnetic level of Bundy.

A similar casting choice was made in 2017 when younger Disney Channel star Ross Lynch was cast as Jeffrey Dahmer, the ‘Milwaukee Cannibal’ known for the serial murders, rape, dismemberment, necrophilia and cannibalism of 17 men and boys from the late 1970s to early 1990s, in My Friend Dahmer (2017). Both Efron and Lynch share a handsome allure and the adoration of a fan base with whom they have grown bestowing them both with a constant limelight which may actually be the point to casting them. Stephen Michaud, one of Bundy’s biographers, described the killer’s methods as being able to ‘[lure] females the way a lifeless silk flower can dupe a honey bee’ so it seems thematically effective to emulate this effect on viewers by casting Efron and other attractive actors. But the true question about this casting choice is: what are the problems that may arise as a result?

It would be short-sighted to suggest that because both Efron and Lynch have young and potentially impressionable fan-bases that their casting would have a negative effect because younger viewers would romanticise the actions of the serial killers portrayed by the heartthrobs. The idea that young, predominantly female, viewers are unable to distinguish right and wrong simply because an attractive actor is performing them is both problematic and insulting. The issue resides around the aesthetic of violence produced by these films.

Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile is written from the perspective of Bundy’s long-term girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer who was unaware of his crimes, which automatically shifts the gaze from one of heinous psychopathy to one of deceived adoration. The culture of violence entwined with its opposite, love and comfort, creates a juxtaposing dynamic exacerbated by the use of actors who symbolise things from childhood nostalgia to overt sexuality. Any violent act is warped by its association with these symbols that does not necessarily call right and wrong into question but distorts the perception of violence as something which isn’t necessarily completely abhorrent.

Such twisted perceptions towards criminal acts have been visible recently in the mass media as the public discuss the discrepancy between Mark Salling’s characters and his actions after his suicide this week. In 2017 Salling pleaded guilty to the possession of 50,000 images of child pornography, yet many Twitter users paid tribute to his Glee character, Noah ‘Puck’ Puckerman, who appeared as a high school heartthrob and bad-boy-turned-good by the power of singing. The aesthetic of Salling and his previous characters obstructed the reality that he was a child sex offender and a predator of the most vulnerable in society.

Yet this concept is not new – Quentin Tarantino is renowned for his aestheticisation of violence so it is no surprise that he is in the process of directing a Charles Manson biopic. The act of perverting violence into something recognisably beautiful assimilates violence with an art form and creates a culture of pleasure and recreation around acts such as serial killing. By enrolling mass viewers into a culture of violence by entangling it with the beautiful it can be suggested that a fear factor is substituted for one of awe, desire and apathy towards the acts performed.

Perhaps this is the point? By aestheticizing the crimes of Bundy, Dahmer and Manson through casting and direction the films produced become a testament to the capacities of the killers themselves. By normalising and, at times, romanticising the violence viewers could be seen to become members of the cults of personality surrounding the films’ subjects. Yet the films themselves are not warnings of the impressionability to viewers which both undermines the intellect of the viewer puts the power of killers on a pedestal. Instead they are demonstrations of the power of aestheticized violence which simply exhibit, with ease, the strange and delicate line that separates violence and its opposites.

Rose Crees

(Image courtesy of Variety/Rex Shuttershock)