From the perspective of a Leeds student on her year abroad at the University of Cape Town, The Gryphon explores the mistreatment of students fighting for free education in South Africa.

Exam season in Cape Town. The regulation bag check and ID scan grant you entry onto the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) rugby field which has been transformed into November Hall- the huge marquee which serves as a temporary exam venue. With the line of portaloos and metal fencing encircling the compound, you’d be forgiven for believing the running joke amongst students- that you’re entering a festival. Yet the private security forces lining the walkways with truncheons in hand, the rolls of barbed wire which enmesh the perimeter, and the German Shepherd dogs that patrol at night, show that this is far from a joke.

These measures were part of the University of Cape Town’s response to the recent #FeesMustFall protests. The final months of 2017 saw students on university campuses across South Africa reignite the call for free, decolonized education. According to UCT management, their response was “designed to ensure exams [were] concluded in a safe, quiet and calm atmosphere.” Yet the presence of German Shepherd dogs (whose historical use as weapons against the black population of South Africa earned them a reputation as ‘apartheid police dogs’) and armed private security (private security have a track record of responding violently to student protests in South Africa during the past few years) was more than unfortunate. Far from creating an environment conducive to learning, it showed a blatant disregard for student well-being, with a major blind spot over how the ‘militarisation’ of campus has racially biased and triggering effects on students. But how did things escalate to this point?

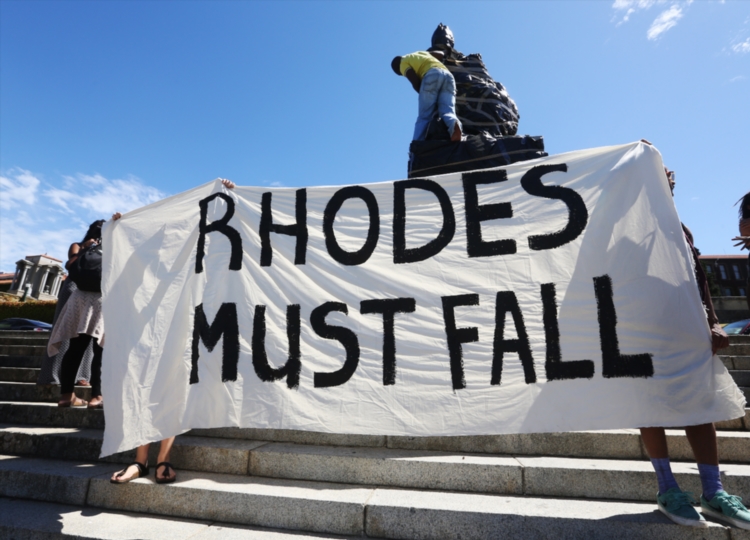

Student protests occupy a unique position in South African history. The 1976 Soweto student uprising marked a pivotal moment in the demise of South Africa’s brutal apartheid regime. The massacre of hundreds of peacefully protesting school children drew international condemnation and gave momentum to the rise of the African National Congress party, which Nelson Mandela was later to lead. Protests continued to be an integral part of student politics over the following decades, but it was the #RhodesMustFall movement in 2015 which once again garnered international attention for South African universities. In March 2015, the throwing of a bucket of faeces over the statue of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes, which occupied a central position on the University of Cape Town’s campus, marked the catalyst for protest actions which resulted in the eventual removal of the statue. The defamation of the statue by students at UCT was a tangible indication of the emotional pain endured by black students attending a university which visibly revered individuals who had historically denied people of colour their humanity. This drew attention to the fact that both the curriculum and the bureaucratic structure of the university prioritised a white perspective, putting students of colour at a disadvantage and maintaining a Eurocentric curricular focus, despite this being the curriculum of an African university.

The 2015 nationwide protests were intended to communicate to universities and government that this inequality could no longer stand. At UCT, students shut down the campus by disrupting lectures, barricading entrances, burning

The 2015 nationwide protests were intended to communicate to universities and government that this inequality could no longer stand. At UCT, students shut down the campus by disrupting lectures, barricading entrances, burning

artwork deemed to be perpetuating colonial ideas, and building a shack on campus to highlight the plight of those students left without housing. The university’s private security and the South African Police responded with tear gas, stun grenades and violence. Students across the country were arrested. Responding to the nine arrests made at UCT this last semester, one UCT student interviewed questioned: “How do you jail people who are protesting for social justice?”

The worn-out familiarity which clashes between students and police have acquired casts doubt over whether anything has fundamentally changed in South African education since the student protests of 1976. The words of anti-

apartheid activist, Steve Biko, ring true today as much as they did when he was at the forefront of the student protests and Black Consciousness movement in South Africa during the 70s. “The basic tenet of Black Consciousness is that the black man must reject all value systems that seek to make him a foreigner in the country of his birth and reduce his basic human dignity.” The use of English as the language of instruction in a country of eleven official languages,

the Eurocentric perspectives which are unquestioningly reproduced in many areas of the curriculum, and not least the treatment of students as criminals, suggest that South African universities such as UCT are rooted in a ‘value system’ that places financial interests above the needs of students.

“The worn-out familiarity which clashes between students and police have acquired casts doubt over whether anything has fundamentally changed in South African education since the student protests of 1976”

In 2016, the University of Cape Town opted to spend over 24 000,000 ZAR to secure its campuses against protesting students. The irony of spending “already deeply constrained resources” on subduing student protests, rather than on

alleviating the financial burdens which were the catalyst for these protests, deepened during the latest round of protests when UCT offered a 30 000 ZAR reward to anyone with information that led to the successful prosecution of ‘illegal’ protestors. The use of such a classic divide and rule tactic suggests it was not students but bureaucracy and buildings which were being prioritized. This was confirmed by the South African government’s reluctance, during this time, to increase its financial contribution towards education from 0.68% of GDP to 1% of GDP- a figure which would still pale in comparison to many developing countries. In Biko’s time, the enemy was clearly the apartheid government, but the oppression of the black population of South Africa today is veiled beneath layers of economic rhetoric, making it more insidious and difficult to fight.

Nevertheless, the fight for free education in South Africa has won some ground. Last month, President Zuma announced plans to begin phasing in ‘free’ (meaning grant-funded) higher education for the poorest South African

students attending public universities and Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges. This would include the 1% contribution of GDP towards education over a period of five years, as suggested by student protestors

and governmental financial advisors. In theory, this would implement a similar model to the UK student loan system, although its efficacy in practice remains to be seen.

Whilst the commodification of education through extortionate fees is something we are painfully aware of in the UK, the consequences could not be more different in a country whose Gini coefficient – a measure of the wealth disparity between citizens – is around twice that of the UK. Financial exclusion from education in South Africa can easily result in slipping to the bottom rung of a social ladder which is heavily mediated by race. The transition of the protests from #RhodesMustFall in 2015 into 2017’s #FeesMustFall reflects a recognition of how intertwined racial and economic issues are, meaning that it is the fundamental values underpinning the education system which need addressing.

Whilst the racial tensions which characterise South African society may be less pronounced in the UK, the need to decolonize education is just as pressing. The Why Is My Curriculum White? campaign which the University

of Leeds has hosted during the past few years was an important step to bringing conversations about decolonisation into the open. It addressed the bias towards European perspectives and forms of knowledge which is embedded in the curriculum, and pointed out how social structures prevent people of colour from accessing higher education and reaching positions from which they could begin to change the structures which perpetuate racial inequality. Universities are supposedly the institutions of learning which produce the thinkers and builders of tomorrow’s world. But, without addressing the historical racial prejudice which is woven into the fabric of these institutions, and making these spaces equally accessible to everyone, there is little hope of progressing towards a more just and equal future.

Mailies Fleming

[Images: The Citizen, LWN, Daily Maverick]